How the Thai photographer and filmmaker sets about empowering audiences to tackle the weight of memory

Within Thailand, the name Nawapol Thamrongrattanarit is synonymous with formally playful character-studies and humorously perceptive coming-of-age tales – films that blend trifling yet affecting plots with an everyday aesthetic. Equally, this Bangkok-born-and-bred screenwriter-director is renowned for populating his social-media-savvy shorts, feature films and commercials with subtly skewed fictional versions of the city’s mildly troubled adolescents and listless young adults.

We have, for example, the alienated teacher’s pet of I Believe That Over 1 Million People Hate Maythawee (2010, a high-school-bound mockumentary short that serves as a piquant introduction to the dry, naturalistic slow-burn of his youth-orientated filmmaking). Moving swiftly forwards through his catalogue, we also find a workaholic freelance creative with an unexplained rash (the protagonist of Heart Attack, 2015), an evangelical lover of Scandinavian minimalism beset by piles of emotional baggage (Happy Old Year, 2019) and a man-child with a frivolous yet homewrecking hobby (‘sport stacking’ – the stacking of cups as fast as possible) is the MacGuffin in his most comedy-driven movie to date, the unusually frenetic Fast & Feel Love, 2022.

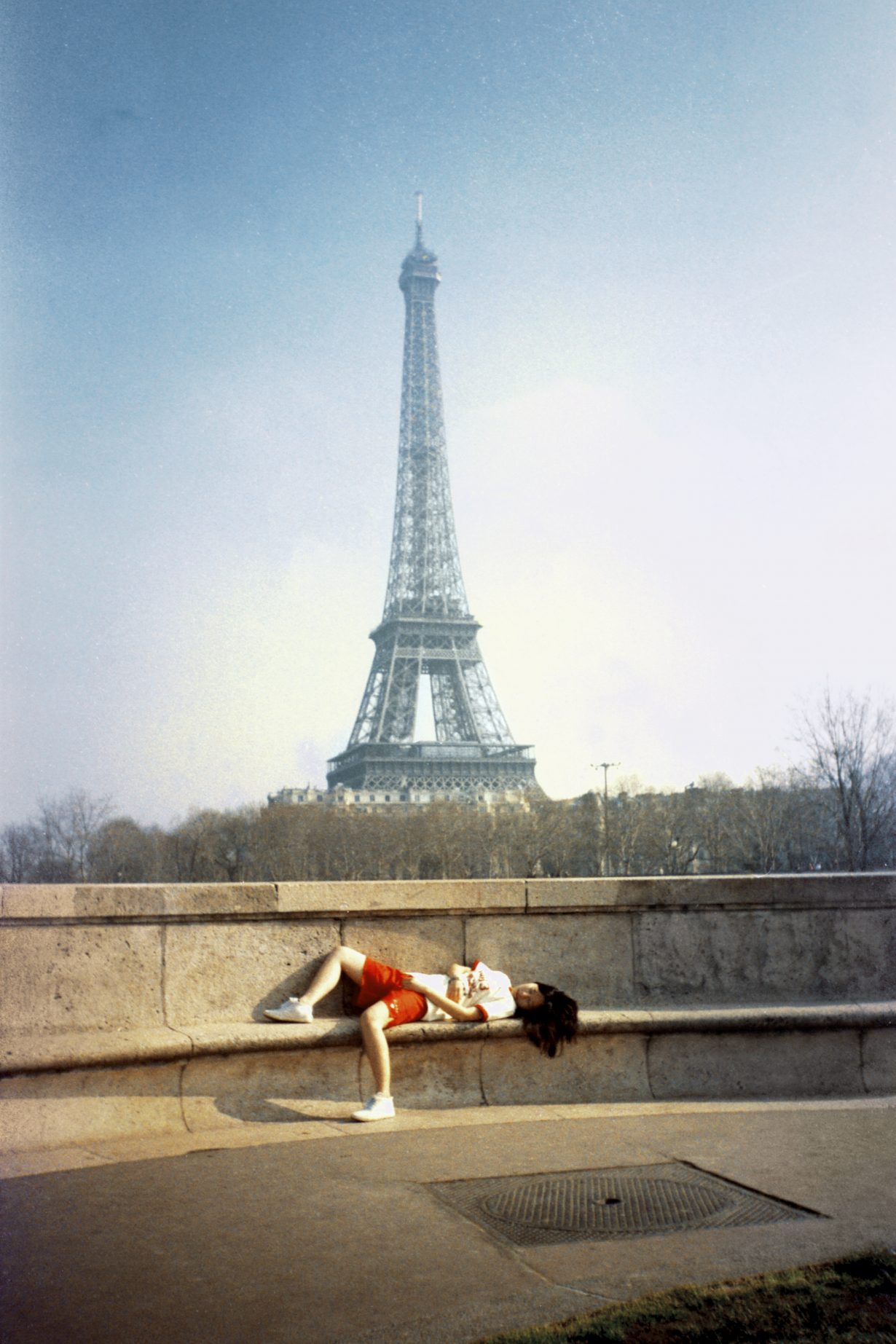

Currently, this cavalcade of out-of-sorts Thai youth also populates HEAVY (2023): a solo exhibition of over 120 large-format photographs – production stills of actors in character and personal snaps – drawn from a collection of over 50,000 images that Thamrongrattanarit has amassed over the course of his career. A ludicrously oversize photo album of sorts, it is on one level a backwards glance at a directorial vision that has enjoyed dalliances with Thai celebrity (local household names Sunny Suwanmethanont and Chutimon Chuengcharoensukying, among others, appear), made inroads beyond Thailand (some images were shot at international premieres and screenings) and found a muse in the mundane landscapes and quotidian detritus of pop culture and cosmopolitan city life (a crushed pack of Hope Menthol languishing on a tiled floor, etc).

On another level, HEAVY is something more high-flown and ambitious: an attempt to ‘transform the archetypal spectatorship of exhibition-going’, as the exhibition text puts it. Seventeen of the 110 × 165 cm prints are spaced along Bangkok CityCity Gallery’s walls, but the remaining 103 or so are stacked unevenly on ten wooden plinths arranged in two columns in the exhibition space. As a result, most images go unseen – until, that is, people start to interact with them. During the preview, actors from the director’s past films teamed up to lift and carry the wood frames sideways between plinths. Similarly, visitors can rearrange the piles – which bear a passing resemblance to Donald Judd’s rectilinear floor sculptures, or excavation pits – until they find an image that resonates.

Watching young groups ferrying pictures around the show is, for me, a reminder that: (a) Nawapol, as he is better known, has a loyal following, particularly here in his natural milieu, Bangkok; and (b) this popularity among millennials has more to do with a sense of affiliation and ownership than passive spectatorship. With his dialogue and plot points often scraped from social media – an approach reflected in his film’s blinking text cursors, expository intertitles and sound effects (social media pings and fingers tapping keys) – and revolving around the humdrum routines, relationships and patois of young adults, he’s earned his indie-auteur stripes by working his way under the skin of a niche Thai demographic. So, when he holds an exhibition that feels very much like an extension, abstraction or celebration of his filmmaker universe – as he has done with HEAVY, and two previous shows at Bangkok CityCity Gallery – the fans descend in droves.

Collectively, these have shown how Thamrongrattanarit often cannibalises, or mirrors, his target audience. For his 2019 exhibition, second hand dialogue, the gallery became a bare, Wonka-esque screenplay factory or lab in which willing participants (lots of them) queued to record three-minute phone conversations with a person of their choosing. In the large ‘visitor room’ adjoining the ‘recording room’, their dialogue was transcribed live and spat out on a screen in front of a rapt crowd. Listening to these conversations being played back over a Tannoy system, seeing the germs of stories take shape in the verbatim transcript, confirmed for me where the moments of situational irony and absurdism, as well as awkwardness and cringe, that we find in his films derive from: this was public eavesdropping as screenwriting. His first ever solo exhibition, i write you a lot. (2016), also had a live screenwriting element: watching the gallery’s comings and goings via CCTV in another room, Thamrongrattanarit adlibbed the stories of random attendees (“a man with colourful shirt tries to study Thai from the script on the table”, etc), and let us watch him work via a wall projection of his computer screen. In an archived recording of one of these sessions, the crowd breaks into ripples of laughter as a boy and a girl start to act out the semifictional characters and off-the-cuff prompts being typed into his word-processing document.

Thamrongrattanarit’s symbiotic relationship with his target audience was perhaps most deftly realised in the sophomore film that sealed his tastemaker status: the fun and freewheeling, if occasionally twee, Mary Is Happy, Mary Is Happy (2013). In it, Thamrongrattanarit twists 410 tweets, appropriated from a real-life Twitter account that he stumbled across, into an episodic teen drama. Appearing as onscreen captions, @marylony’s epigrammatic life tips (‘It’s dangerous not to know yourself’) and stream-of-consciousness ramblings (‘My portfolio is very minimal’) drive forward and dictate the actions of two schoolgirls as they discuss and navigate everything from yearbook projects to puppy love. It was a sleeper hit among the age group it depicts, largely on account of its verisimilitude to their lived online and offline experiences and liminal setting (Thamrongrattanarit is an assiduous location scout, with a good eye for peeling modern architecture that signposts Bangkok’s halting socioeconomic progress), but also his actor’s performances.

An outlier in a country in which directors tend towards producing cookie-cutter TV dramas featuring one-note characters, Thamrongrattanarit has a proven knack for getting the best out of his stars. In part this is because they appear ordinary and normcore-clad, but mainly it’s because he offers them a rare chance to deliver a realism that’s glaringly absent from most mainstream Thai films or television. Stories evolve through the cut and thrust of small talk and repartee, not melodrama.

Then there are his long-form commercials: another signature component of the Nawapol brand. On a pragmatic level, branded marketing videos – some of which have racked up millions of views – offer, as he told me back in 2018, “an opportunity to experiment, learn more filmmaking skill, explore new casting and practise pitching projects before going back to make my own new feature”. But they’re more than simply opportunities to road-test new actors or approaches, or proof of concepts. Pull up a few on YouTube and you’ll quickly see how his trademarks – “Realistic, character study, political inside, black comedy and Thainess”, as he once put it to me in an email exchange – align across all the mediums he dabbles in, no matter how nakedly corporate their end goals.

In, for example, his Cannes Lion-winning promo for a Thai banking app – in which deadpan delivery meets rapid-fire cuts and a growling acid-techno soundtrack – a socially awkward schoolgirl who struggles to make friends gets on a bus to a new school (Friendshit, 2017). En route, her best friend screams advice for how to become popular – “Don’t be complex. Be mainstream!” – while performing daredevil scooter stunts alongside the speeding vehicle. This is Thamrongrattanarit at his most clownish and dialled up, and yet Friendshit’s aesthetic and core concerns (beyond its cursory plug for the banking app) – interpersonal relationships, how technology is shaping the experience and argot of a generation, humour as release for pent-up ennui, fitting in and finding your place – is of a piece with much of his back catalogue. He’s called this approach, partly born of the perennial difficulties of getting films funded in Thailand, the ‘noodle stall method’, likening it to a family recipe. ‘If the noodle is good, customers will find you. And there’s no need to tweak the taste,’ he told a Thai interviewer in 2018.

HEAVY, with its approximately 120 photographs plucked from across this variegated career (including his commercials), and crowds manhandling them, is arguably yet another reminder of this modus operandi – and its enthusiastic domestic reception. For Thamrongrattanarit, however, the groups ferrying pictures around the exhibition also personify something interior: the Proustian melancholy he felt while putting it all together. The idea for HEAVY came about, he explained, when, after ordering a 110 × 165 cm print to his home, the delivery man refused to carry it in. After doing it himself, Thamrongrattanarit decided then and there that carefully piloting a giant frame is a solid metaphor for the intangible burden of the mental furniture we are all saddled with. Lifting and carrying then became the participatory conceit for his first official photo exhibition – the curating of which, if we take his artist statement at face value, was a test: “The digital memories, initially perceived as weightless, suddenly become heavy when they are all piled up in front of you”.

While this conceptual framing may smack slightly of contrivance, Thamrongrattanarit – a self-confessed dabbler in the fresh forms of audience engagement the white cube affords him, not an artist per se – has a track record of using objects to reify the workings of the mind, to make tangible his thinking on what he has called “memory management”. Two of his most singular films attempt something similar.

In 36 (2012) – the experimental feature debut that first gained him international recognition – a location scout, Sai, chats with a politely spoken art-director while she conducts a photographic survey of a rundown rongraem manrut (love motel). In the first half of this hour-long film, which is told through 36 static shots (the number of exposures in a standard 35mm film roll), Sai explains how she stores her memories as jpegs on hard drives (“one for every year”). Which helps explain her cavalier attitude to the moments they bond over. In shot seven, titled ‘A red-violet bird was flying in the sky’, she brushes off his comment that “It would be prettier if you look at it with your eyes” with a curt “Yes, but now I can keep it”. Later, however, when the ‘2008’ hard drive containing the only reliable record of their time together fails, the film sets about challenging her approach to remembering. “It’s like the whole year has been lost,” she tells a friend, before heading off to try and repair it.

And then there’s the antihero of Happy Old Year (2019), a feature produced by Thai film studio GDH 559. Back in Bangkok after three years in Sweden, aspiring interior designer Jean (played by Chuengcharoensukying) is tiresomely smug about the style she came to admire there: “Minimalism is like a Buddhist philosophy. It’s about letting go,” she tells her sceptical mother and brother, trying to convince them to let her convert the untidy old family home into a sleek white office.

Initially she makes good headway – “garbage bags are like black holes”, she says while stuffing them full – but her enthusiasm soon wanes when certain objects trigger pangs of repressed emotional pain. And so Jean pivots from tossing out to returning things – a double bass she borrowed, a ghosted ex’s camera – to their owners. And this process of returning and reconciling proves even more traumatic. “We see what we want to see. We remember what we choose to. That’s all there is. Just get on with your life,” the no-longer-ghosted ex yells at Jean, shortly after his jealous new girlfriend has run for the hills. In Thamrongrattanarit’s most tear-sodden coming-of-age tale so far, memory is not a framed photo that we must lug around, nor an old hard drive that we must fix, but a clutter that we must, as adults, learn to carefully sort into piles of trash and treasure – and sometimes hold onto forever.