A little surreal, a little subversive, very funny, often obscene – the artist discusses how the current season of isolation has impacted her work

People love to play a round of art-historical I Spy when they encounter a Nicole Eisenman painting. Her multidecade career synthesises everything from German expressionism and social realism to comic books and TV culture, sometimes incorporating multiple styles within the same canvas. It resists categorisation yet, like porn, you know it when you see it. A little surreal, a little subversive, very funny, often obscene. Her paintings blend social chronicle with commentary and feature a recurring cast of friends and lovers, but strangers, when they appear, are depicted with the rare warmth of intimacy. I imagine she must be a tremendous people-watcher and wonder how the current season of isolation has impacted her practice.

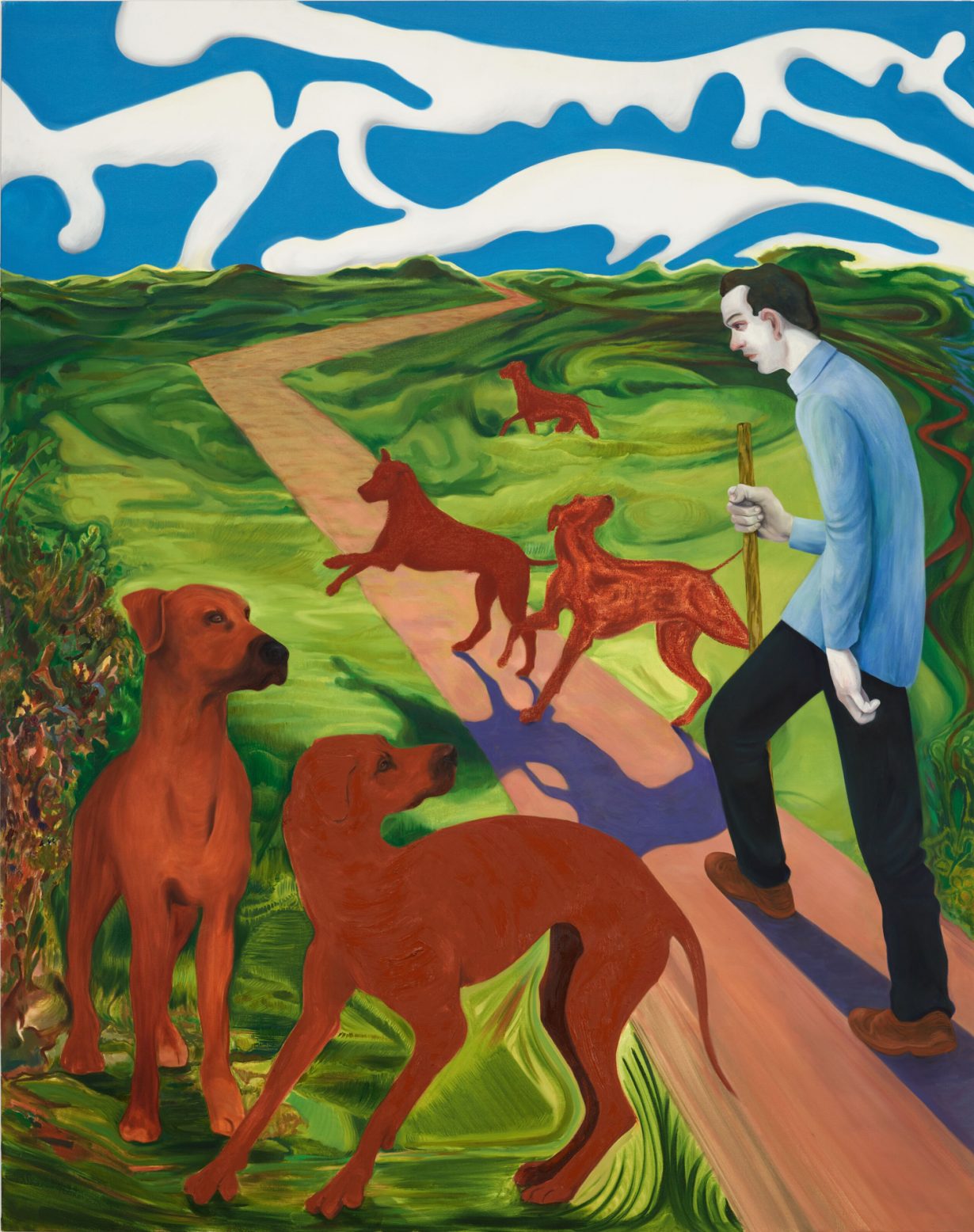

Speaking over the phone from Brooklyn, Eisenman says that not much has changed: she makes the short bike ride to her studio and carries on uninterrupted, making work, quietly, by herself every day. Mentally, however, it’s a different story. “You go through waves of disbelief and dysphoria and depression. Everyone has their own techniques for keeping yourself from going into the weeds,” she explains. This general mood has seeped into one painting she has made this year — dogs frolic in the foreground of a rather English pastoral — which will be on view in her first show for her new gallery, Hauser & Wirth, in Somerset (making it her third gallery, with Anton Kern and Vielmetter Los Angeles). The same dynamic suffuses her practice as a whole: part escape valve, part reimagining the world as it could or should be.

© the artist. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

In recent years, Eisenman has also become known for her sculptures, following a star turn at the 2017 Skulptur Projekte Münster. Sketch for a Fountain, a collection of bathers lounging around a small pool, gained notoriety when it was repeatedly vandalised with swastikas and cartoon penises and was even decapitated; permanent iterations have since been installed in Dallas and Boston. Sculpture, for Eisenman, necessitates additional considerations of both usage and spectator. The more recent versions of her fountain include chlorinated water for kids to play in and benches for tired parents or nannies.

For her 2019 Whitney Biennial participation, she installed a monumental procession of figures on a rooftop terrace. She wanted to recreate the visceral, bodied “scale change” felt at a protest, at once buoyed by the energy and dwarfed by the mass of people, describing it as “this feeling of power you can get when you’re in a crowd and walking amongst these figures that are bigger than you. It changes your sense of scale in the universe: you feel humbled by it, you feel small in a good way, and you feel powerful in that connection to the group.” But she couldn’t resist a little fart humour either: one sculpture features a fog machine that periodically blows smoke out of one of the protagonists’ asses.

Eisenman’s breakout came at the 1995 Whitney Biennial, where she showed a monumental WPA mural-esque apocalyptic scene of a bombed-out Whitney Museum: at its centre, the artist, still painting amidst the bodies and rubble and rent canvases. The work eerily prefigures the much later controversies that would lead to board chairman Warren Kanders resigning after Eisenman and seven other participants withdrew from the 2019 biennial (after the resignation, the artists reinstated their works).

She is a rare painter who seems to get better with time, no matter how impossible it might seem that she could surpass her past achievements; she received a MacArthur ‘Genius Grant’ in 2015 for quite literally ‘[restoring] cultural significance to the representation of the human form’. But we can understand her as a master abstractionist too. Rather than distilling the body down to a few features – some eyes, a mouth, some genitals – her paintings abstract race and gender while remaining solidly figurative.

As such, her paintings serve as a kind of barometer for cultural attitudes towards gender and sexuality. Early bawdy paintings like Betty gets it (1994), which features prehistoric tradwife Betty Rubble getting it from her next door neighbour Wilma Flintstone, and the 1990s identitarian impulse led to Eisenman’s inclusion in not one but two shows titled ‘Bad Girls’. Then, her characters were identified as lesbians; today, the same audience might understand them as genderqueer.

Past bodies of work have leaned heavily on allegory and metaphor, but Eisenman generally feels pinned down by the limitations of language, and the way it reduces bodies – including her body of work – to a series of references. But this lexical change is one that Eisenman, who identifies as genderfluid, welcomes. “I was so resistant to being called a lesbian painter because it felt just too narrow and confining,” she explains, adding that in recent years she has come around to liking the identification of lesbian again. “It does begin to feel more radical when you have straight, married people being like, ‘we are queer!’ We all know people like that.” I think of a missive in Artforum earlier this year from Ridykeulous, the curatorial collective Eisenman cofounded with Al Steiner to demarginalise queer and feminist art, which contained the excellent line – and frankly, clarion call – ‘separatism is more than a mere 6’.

Questions of representation and responsibility dogged her early years, and have more recently returned to the fore, especially when considering figures installed in the public realm. “I’m so aware of the problems of putting female bodies, genderqueer bodies, trans bodies, representing different kinds of bodies and putting them in the public realm and exposing them to potential violence,” she says. And while attacking statues is not the same thing as the current epidemic of violence against (particularly Black) trans people, it still holds symbolic charge. Even if, in Münster, these were random local teenagers and not transphobic neo-Nazis (Eisenman’s grandparents fled Germany in 1937) “what you end up with is a representation of a trans body being defiled. It’s frightening and ugly.”

The same concerns extend to how she depicts race and ethnicity. Mustardy yellows are particularly common, joined by blues and greens as well as the usual flesh tones – often all orgiastically crowded in the same painting, as with the seductively louche houseparty of Another Green World (2015). She sees portraying skin tones as an unavoidable imperative when painting, one from which sculpture allows some release. “There are times in my painting where I don’t pay attention to localised colour and skin could be any colour. There are other times where I’m much more specific and it’s like Caucasian skin or brown skin or Black skin.”

As for her astonishing command and subsequent bricolaging of Western art history? “I get bored,” she explains, citing her admiration for the English novelist Penelope Fitzgerald and her ability to switch between styles and genres as the subject requires. “It’s a combination of being indecisive, being bored and just liking the way things look when they’re next to each other, things that don’t match each other.”

The past two years, following a papermaking residency, she has been experimenting with paper pulp, creating posters with an almost sculptural quality. “It’s a really strange process,” she explains. “You take liquid pulp, you squeeze it out and it comes out and flops in sloppy lines, so there’s a real limit to the mark-making you can do, and what kind of texture you can get.” Instead of trying to fight it and make painterly work, she let the material dictate the end product, which she alternately describes as crude and charming. The resulting posters are beautifully blobby and blurry, and feature slogans like INCELESBIAN, and NICOLE SARAH SARAH NICOLE, in reference to her girlfriend, the writer and critic Sarah Nicole Prickett. Along with the fountain and a scaled-down Whitney processional, they will also be on view in Somerset. Unlike her usual sombre palette, these works are awash in bright oranges and the baby pinks and blues of a wildfire-starting gender reveal – except here the punchline is, there is no gender.

Where I Was, It Shall Be, an exhibition of new works by Eisenman, is on view at Hauser & Wirth Somerset through 10 January

Rahel Aima is a writer based in New York