Curated by Anselm Franke, the touring exhibition Animism makes its Asian debut in OCT Contemporary Art Terminal (OCAT), Shenzhen. The layout of works in OCAT’s 1,000sqm oblong hall is well proportioned: the big screens hanging from the ceiling for film and video projections create an archaeological field of moving pictures, while rows of display cases beneath them offer a close look at smaller drawings, videos and photographs displayed in an archival style.

There is no given visiting route; visitors must find their own path when it comes to constructing relevance among the works. This is a challenge, but a respectful one: without a simple explanation or singular narrative, everyone has to develop his or her own logic, based on the evidence of the exhibited material.

Originally deployed by nineteenth-century anthropologists, the word ‘animism’ at first referred to a certain kind of worldview in which subject and object are not divided according to the modern Western view. But the show has no intention of calling back the spirit of the premodern age.

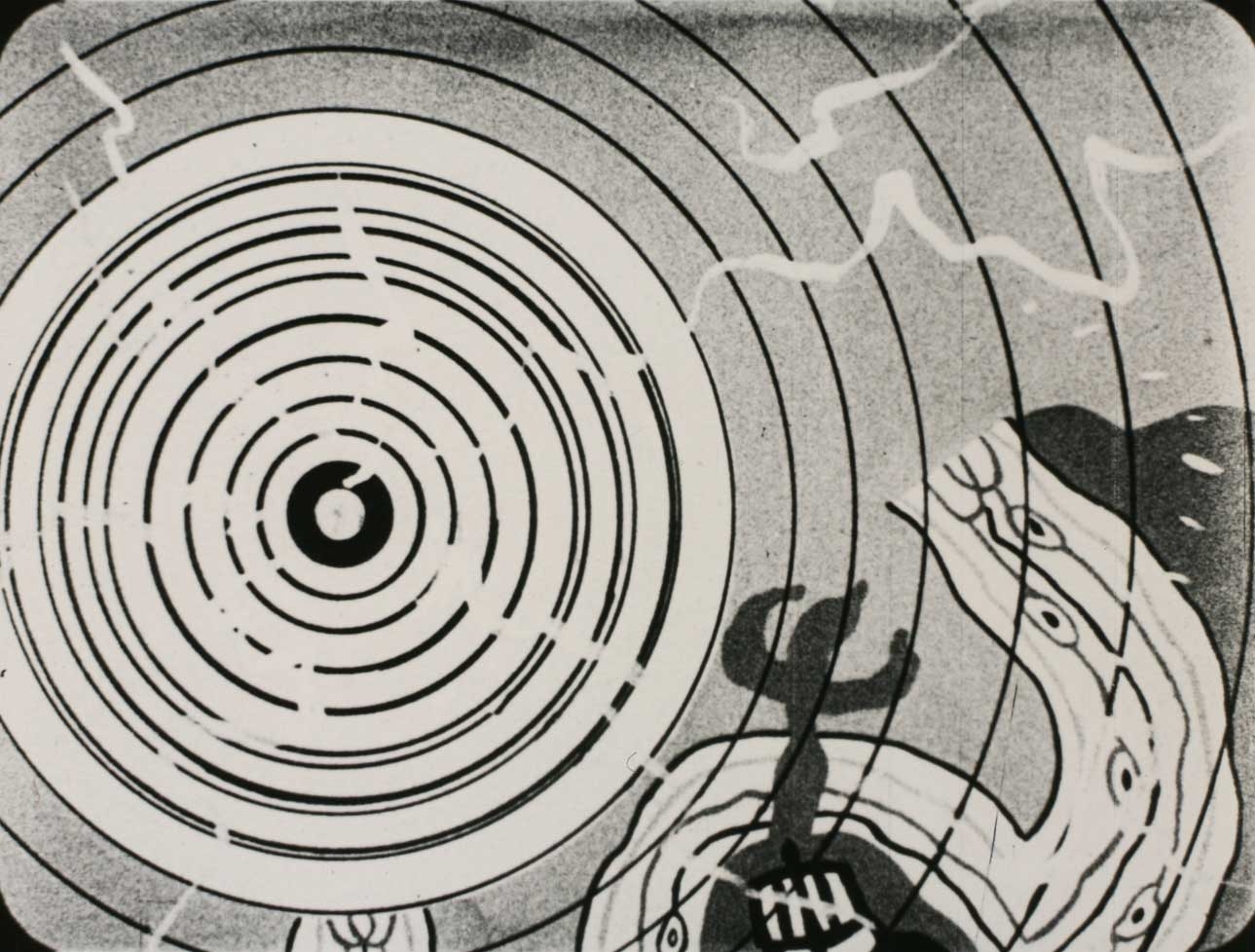

It brings together works including historical documents (eg, Animal Magnetism, an illustration from the eighteenth century), films (Chris Marker and Alain Resnais’s Les Statues Meurent Aussi, 1953), archival displays (the second card of the Rorschach inkblot test, 1921) and contemporary art, to open up powerful discourse arising from a series of dualisms: modernity and premodernity, urban and natural, rationalism and barbarism, European and the other (alien).

Walt Disney’s short The Skeleton Dance (1929) offers a good starting point from which to explore the show, in part for its highlighting of the idea that pictures can be ‘animated’. Some works about consumerism propose the question of how the objectified subject yearns to become an object – a reversal of projecting subject upon object (the projection theory to interpret ‘animism’).

If we do not immerse ourselves too deeply in one work, but go through the works around the exhibition hall, we would be able to picture clearly how the establishment of the modern order takes place alongside the process by which the irrational, alien and primitive cultures were defined as ‘the others’. Angela Melitopoulos and Maurizio Lazzarato’s ongoing project on Félix Guattari (three-channel video installation Assemblages, 2010–) and Paulo Tavares’s Non-Human Rights (2011–12) explore how such ideas regained currency as ‘critical weapons’ against modernity in the postmodern era.

To emphasise the fact that the real target of his project is modernity, Franke once wrote the following (haunted by the spectre of Marx): ‘A ghost is haunting modernity – the ghost of animism.’ If ‘ghost’ as a nonphysical being is something that appears in unexpected places at unexpected moments, the same expression could also be used for the hidden subject of the animation project: colonialism.

We are haunted by the ghost of colonialism as well. Animism as an exhibition does not simply rethink colonialism at the political, economic and psychological level, but also questions the colonialism that appears anywhere, at any time, in human thought and knowledge systems. According to recent critiques of modernity, everyone is colonised by modern concepts, even those who play the role of the colonist.

That’s why I was haunted by the suspicion that by touring around the world, the show itself is practising a kind of intervention. It is one at an atomic scale, going into the mind of every audience member – no matter whether or not they aspire to such an intervention.

This article was first published in the November 2013 issue of ArtReview Asia