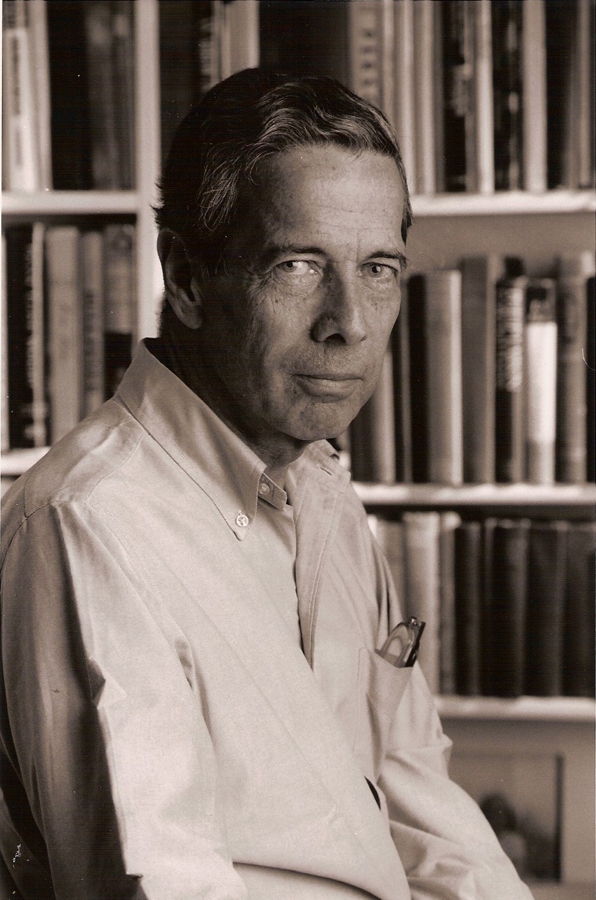

Calvin Tomkins’s career as an art reporter began with an interview with Marcel Duchamp in 1959 for Newsweek magazine, which stirred his interest in contemporary art. But it was a series of four profiles he wrote for The New Yorker in the early 1960s – on Jean Tinguely, Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage and Duchamp – that fully revealed to him the exciting possibilities of art. According to Tomkins, these four artists comprised ‘a group of people who were all thinking along the same lines, and that really taught me more about what was going on in contemporary art than anything else. This was so powerful, that art could be all these other things.’ Ever since, Tomkins has pursued an insatiable curiosity about art, reporting on artists and their milieu, from Georgia O’Keeffe to Jeffrey Deitch, making him uniquely well positioned to comment on influence and new directions in the artworld.

A staff writer for The New Yorker since 1960, Tomkins has also published over a dozen books, most recently Marcel Duchamp: The Afternoon Interviews (2013), along with new editions of The Bride and the Bachelors (2013), Living Well Is the Best Revenge (2013) and Duchamp: A Biography (2014).

Bridget McCarthy

I thought we might start where it all started for you: with Duchamp. You’ve said elsewhere that Duchamp is the most influential artist of the past 100 years. In what ways do you see his continuing influence today?

Calvin Tomkins

It seems to me that Duchamp’s influence just continues to expand. It’s reached a point now where a great many young artists – maybe all young artists – are influenced by him, sometimes without even knowing it. As the grandfather of what came to be known as Conceptual art, his idea that art was not solely and exclusively a visual thing has permeated the atmosphere. It’s also made everybody who’s interested in art – not just artists, but everybody – ask the question, ‘What is art?’ I think until Duchamp, people could pretty much assume that they knew what art was, but since then, nobody knows what it is. It’s infinitely expandable and has been expanding in all directions. I think that largely goes back to Duchamp.

BM How would you define art today?

CT I don’t think it can be defined. I think that’s one of Duchamp’s contributions. He said at one point that the readymade is really a form of expressing the impossibility of defining art. Art is too diffuse, too vital. It’s always growing and changing. Certainly, we no longer can think of art as something that hangs on the wall. That is the work of art. The art remains with the artist.

Art is so many things now. An artist can go in any direction. That makes it much easier in some ways and much more difficult in other ways. It’s much easier to be a bad artist now. It was always quite possible, but it’s much easier now.

There’s this mantra: if art can be anything, it can also be nothing. It can be of no interest or importance at all. It’s completely open-ended. Duchamp gave the freedom for this situation to become widespread, but the interesting thing is that hardly anybody imitates Duchamp. His attitude can be learned from, but the things he did cannot

BM Because there’s more exposure, even for bad artists?

CT Because there’s such total freedom: because art can be anything. There’s this mantra: if art can be anything, it can also be nothing. It can be of no interest or importance at all. It’s completely open-ended. Duchamp gave the freedom for this situation to become widespread, but the interesting thing is that hardly anybody imitates Duchamp. I read in somebody’s essay that there had been, to that date a few years ago, 27 works of art based specifically on Duchamp’s last work, the Étant Donnés [1946–66]. So people are trying to imitate him, but I don’t think he’s very imitable. His attitude can be learned from, but the things he did cannot. One of the interesting things about Duchamp’s work is that it’s so exquisitely made. His craftsmanship was amazingly good, and he was willing to devote infinite time. Richard Hamilton told me that when he was making his replica of The Large Glass [1915–23], with Duchamp’s permission he came and studied it, but he could not reproduce the detail as precisely as he wanted to. It was just too exquisite, in a way.

BM Do you think people are aware of that as part of Duchamp’s legacy – the craftsmanship and patience?

CT I doubt it. I don’t think that’s really a well-known fact about Duchamp. It’s his attitudes and his insistence on freedom and thinking about art as a mental thing that have really had such a big influence.

BM You wrote something in the introduction to your book Post- to Neo-: The Art World of the 1980s [1988] that I wanted to ask you about. Regarding Minimal and Conceptual tendencies in art in the 1970s, you wrote that they came right out of Duchamp, ‘who had been rediscovered in the late sixties by earnest ideologues who carry Duchampian ideas to their logical (and therefore non-Duchampian) conclusion’. What do you mean by that?

CT With Duchamp you never get a conclusion in that sense. Duchamp is all about openings and contradictions and possibilities. A mistake that is made over and over again by people who are thinkers about Duchamp is that they try to figure out a system that explains him. Duchamp had no interest in systems, and his work cannot be explained that way. Duchamp eludes all attempts to trap him in a systematic theory.

BM In your New Yorker profile on Duchamp, reprinted in The Bride and the Bachelors, you quote him as saying that ‘fifty years later there will be another generation and another critical language, an entirely different approach’. That was 50 years ago. Do you thinkhis prediction has come true? Or given the fact that he himself continues to have such a strong influence, does that suggest continuity?

CT You know, I don’t really know. I often think a time is bound to come when there’s a counterrevolution against Duchamp, when some artist or group of artists appears on the scene with a whole new attitude and approach. So far it hasn’t happened. You could say that the Abstract Expressionist period was the anti-Duchampian era of the art establishment. It was no coincidence that during that period, in the 1940s and early 1950s, Duchamp was forgotten. A lot of people thought he was dead. It wasn’t until the late 1950s and early 1960s that the interest in him revived. It came slowly, but it was a really major revolution. But no revolution lasts forever. You keep thinking that sooner or later there has to be a counterrevolution, and that Duchamp will be relegated to a place in art history that is no longer the present. I don’t know when it will happen, but it will have to happen eventually.

BM Have you seen any kernels of what might be a new revolution? Maybe it’s a particular medium?

CT It’s possible that this growing interest in the social value of art has the seeds of that. There are so many artists who want their work to resonate in society, to go outside of the artworld, to go outside of art. To my mind, that could become an anti-Duchampian situation, but there are so many tendencies now. He was the one who let a thousand flowers bloom, and they’re all blooming.

BM Are there any artists in particular that you’re thinking of when you mention the social value of art?

CT One of them that comes to mind is Paul Chan, whose art, to me, is completely unpredictable. You don’t really know where he’s going to go with it. It goes from the Marquis de Sade to technology, and he is so bright and smart and his mind is so alert that it could go off in a completely new direction.

BM Speaking of Paul Chan, for last year’s ArtReview Power 100 issue, Rirkrit Tiravanija created the artwork, and as part of it he used an image of a spread from your book Marcel Duchamp: The Afternoon Interviews, which was published in 2013 by Chan’s publishing enterprise, Badlands Unlimited. It’s an image of pages 28 and 29, where Duchamp talks about how at the time, in 1964, a spiritual approach was lacking and how the commercialisation of art was the leading influence on art at the time. That passage struck me as sounding very contemporary. What is your sense of how that commentary resonated then versus now?

CT Rirkrit is certainly one of the artists who is involved with the social aspects. The whole idea that art can be him cooking for you is quite revolutionary. But I don’t really know how to answer that. The whole thing is contradictory, because Duchamp warned against the increasing commercialisation of art, and his prophecies have been borne out way beyond anything he could have imagined. Now the commercial aspects of art have become, in many ways, more important than the art. You can see this leading to a real crash, which would be connected with the breakdown of society – the breakdown of corporate Western society.

In some ways, art could have an influence on that. These artists now who want to go beyond art, meta-art, and have an influence on society: well, if society breaks down as it seems to be doing, these artists and others like them may be able to play a much more important role than they have before. In fact, it’s occurred to me in idle moments that we have this situation where there are not enough jobs and where unemployment is a major blot on capitalist economy. We also have this overproduction of artists in the world. All over the Western world, new artists are being hatched every year.

Thousands and thousands are coming out of college. Well, what if the two things are related? What if it turns out that the solution to unemployment is that, as Joseph Beuys said, everyone is an artist? If what’s left of governments or the economic order will go along with that, it would solve the unemployment problem, because everybody who’s not actually working can become an artist. It might, who knows, even solve some of the economic problems, because artists don’t demand the kind of social benefits that the rest of us take for granted. They can figure out new ways of living and existing with the resources at hand.

BM Is that a Duchampian conclusion?

CT [laughter] Maybe. I can imagine Duchamp thinking this. He said things like, ‘Why should people work?’

BM You’ve interviewed so many fascinating people over the years. Your writing really seems to capture their personalities. How does it feel to think of your – self as an influential person, for example, in terms of how we see these people or how your writing has impacted others?

CT Well, it’s very nice. I do get people, including artists, who said they read The Bride and the Bachelors when they were in art school, or even before, and that it had a big influence on them. That’s a good feeling. I attribute it to this thing, this stroke of luck, that I just went from one artist to the other in the beginning, and then discovered that they were all related in these different ways. It gave me a sense that I’d stumbled on something. Of course, now it’s been written about a great deal, but I think in the early 1960s it wasn’t written about very much, so I think it’s possible that a lot of artists went through the same process I did. They began to try to figure out what art was instead of just trying to pursue it, and this led them in all sorts of new directions.

BM As a closing question, is there anything you wish you would be asked?

CT Well, I’m not used to being asked; I’m used to asking. You know, I’ve always had a slight problem with the fact that some people think I’m a critic. I’ve never had any interest in functioning as a critic. I respect the art of criticism and I read critics with great interest and delight, but I never wanted to be one. I’ve always seen myself as a reporter on art. I think what’s been happening in art in this country and abroad for the last 50 years is so interesting and so varied and so connected with life in America that it’s perfectly legitimate to make an effort to report on it, to try to give a picture of the artist and the art as it’s been happening.

You know, John Cage said that at any one time one of the arts is doing the talking and the others are listening. At the time he said it, he felt it was music that was doing the talking and the others were listening. I think that since the early 1960s it’s art that’s been doing the talking. When I started, there was no art coverage in the news magazines and there was no regular coverage, even in Time. There was no critic. Contemporary art, particularly, was considered a ridiculous and foolish aberration. It didn’t have anything to do with art, according to a lot of people. The change has been so enormous. The artworld, which used to be about 20 people, is now a big international industry. There’s good and bad about that, but the whole thing has changed and expanded so enormously. It’s been very, very interesting to watch, and to try to keep some sort of track of the changes and the different directions and how they worked out.

This article was first published in the November 2014 issue.