This article forms part of a yearlong survey (in monthly instalments) in which artists, curators and cultural commentators explore the question of what African art (of the contemporary flavour) does or can do within various local contexts across the continent

In her paper ‘National Mythology: Past and Present’ (2000), the Estonian cultural theorist Epp Annus, in reference to Benedict Anderson’s concept of the nation, describes nations as being in a seesaw between Past Perfect and Future Perfect tenses. The Past Perfect she is talking about is the national myth, the epics from which all nations and peoples are born, tales of brave men and gods, narrations of heroes and battles won, sculpted to contain a national identity. Annus proceeds to explain that this mythological Past Perfect is needed to establish or simulate a possible Present Perfect of the future.

In the case of Ethiopia, this Past Perfect is the legend of Queen Makeda of Ethiopia, the Queen of Sheba’s visit to King Solomon of Israel as detailed in the Kebra Nagast (The Glory of the Kings, c. 1314–22). This tenth-century BC (as claimed by some historians) legend vividly recounts the biblical encounter of the Queen of Sheba with King Solomon. The story of their offspring Menelik I, who grew up in Ethiopia but went back to Israel to visit his father, and is also said to have brought the Ark of the Covenant to Ethiopia to the holy kingdom of Axum, is now known and has been paraphrased time and again through all mediums of narration. Axum is also known for its great civilisation, culture, architecture and also its tradition of engineering, which can be seen in the many fascinating obelisks/steles that were carved and erected by the Axumites to indicate special underground burial chambers, especially for some of those heroes mentioned in the national myth.

What happens if one is robbed of this Past Perfect, this myth in which nations and peoples find their foundations…? And ‘robbed’ here is not meant to stand as a metaphor for anything, but a synonym for stealing

But what happens if one is robbed of this Past Perfect, this myth in which nations and peoples find their foundations…? And ‘robbed’ here is not meant to stand as a metaphor for anything, but a synonym for stealing, sequestrating, taking captive, etc. If Annus’s theory should hold its ground, how can a people imagine a Future Perfect without this Past Perfect to seesaw to?

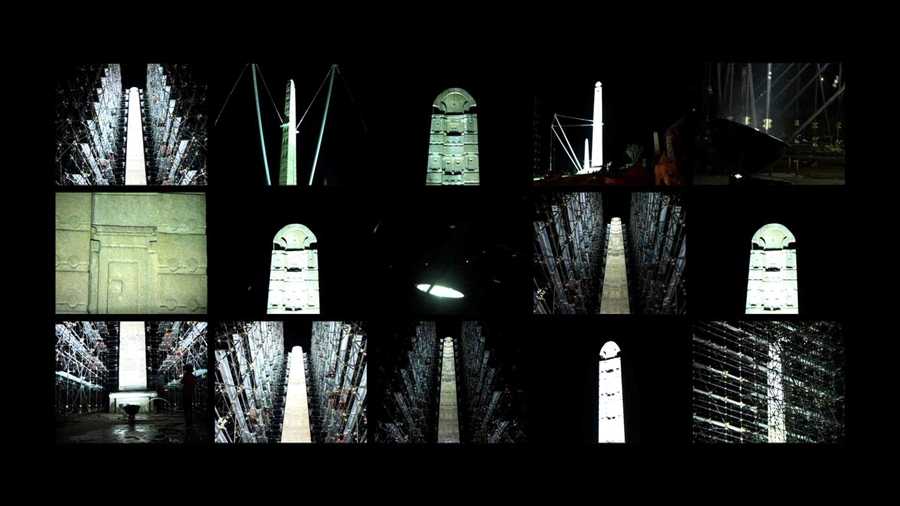

The multimedia artist Theo Eshetu seems to have been concerned with this reality too. The Return of the Axum Obelisk (2009), a complexly stratified multiscreen video piece, not only in form but also in content, brings together mythological, religious, political and aesthetic issues. Using a visual language reminiscent of traditional Ethiopian icon paintings, Eshetu narrates the reestablishment of an equilibrium, which could be likened to the seesaw of the Past Perfect and the Future Perfect.

Rewind… Forty years after Italy had lost the war against the empire of Ethiopia in its unsuccessful colonial adventure at the Battle of Adwa, the second Italo-Abyssinian war, in 1935–6, saw Italy as a victor. To reward itself for this victory, Italy took with it in 1937, as a trophy of war, the 1,700-year-old Obelisk of Axum, which was later mounted in Rome (as was Ethiopia’s other imperial symbol, the bronze Lion of Judah that had been unveiled for the coronation of Emperor Haile Selassie I in 1930). The dispute between Italy and Ethiopia regarding the repatriation of this symbol of Ethiopia’s national identity only came to an end in 2005, when the obelisk was sent back to Ethiopia, then mounted in 2008.

As the irony of destiny shaped it, Theo Eshetu – who was commissioned by UNESCO, the facilitator of the repatriation, to document the return and the reinstallation – had had a long relationship with the obelisk. Not only because of his Ethiopian origin but also because he grew up in Rome, where his father worked in the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization office in front of the obelisk at the Porta Capena square, and also because, before UNESCO ever contacted him, he had been looking for possibilities to do a film on the return of the obelisk of Axum.

The Return of the Axum Obelisk portrays in a nondocumentary manner the national myth of Ethiopia, the technical and social challenges around the return and reinstallation of the obelisk, the celebrations and regaining of a national pride that came along with this endeavour, but also moments of reconciliation between Italians and Ethiopians. The video installation thus chronicles the heights of colonial conflicts, but also the emancipation of a people. It questions the role of monuments as spaces of portrayal or projections of public memory. Symbolism plays an important role in the piece, as the varying meanings and epistemologies that are given to, or that such public monuments, such historical objects, such national fetishes assume become evident. The obelisk of Axum itself is lucky to have had various connotations ranging from religious, phallic, war booty and more attached to it.

Nations and peoples need their myths, their Past Perfects, to be able to extrapolate from them possibilities of Present Perfects and, even more so, Future Perfects.

Theo Eshetu will be on show at Tiwani Contemporary, London, from 25 September to 31 October 2015.

This article was first published in the October 2014 issue.