I feel the need to confess. The first time I encountered Robert Melee’s photographs of his mother – drunk, seminaked and in theatrically sexualised poses – I felt distinctly uncomfortable. It was in a major contemporary art museum, part of a larger Melee installation, and I found myself very aware of not wanting to make eye contact with the female guard. A Dozen Roses, Melee’s first exhibition to stage the photographs alone, is a forbidden love song. But presented as straight photography, it’s somehow easier to see.

It’s not as if photographs of eroticised transgression are new in the artworld. In fact Melee belongs to a lineage that extends from Larry Clark and Nan Goldin to Richard Billingham and Leigh Ledare, among others. Unlike the Lolitas scrutinised by an ageing Clark (male and female alike) and the access to a kind of class voyeurism that catapulted Billingham to his own juvenile success, Melee makes us prurient witness to an Oedipal revenge plot with Jocasta centre stage.

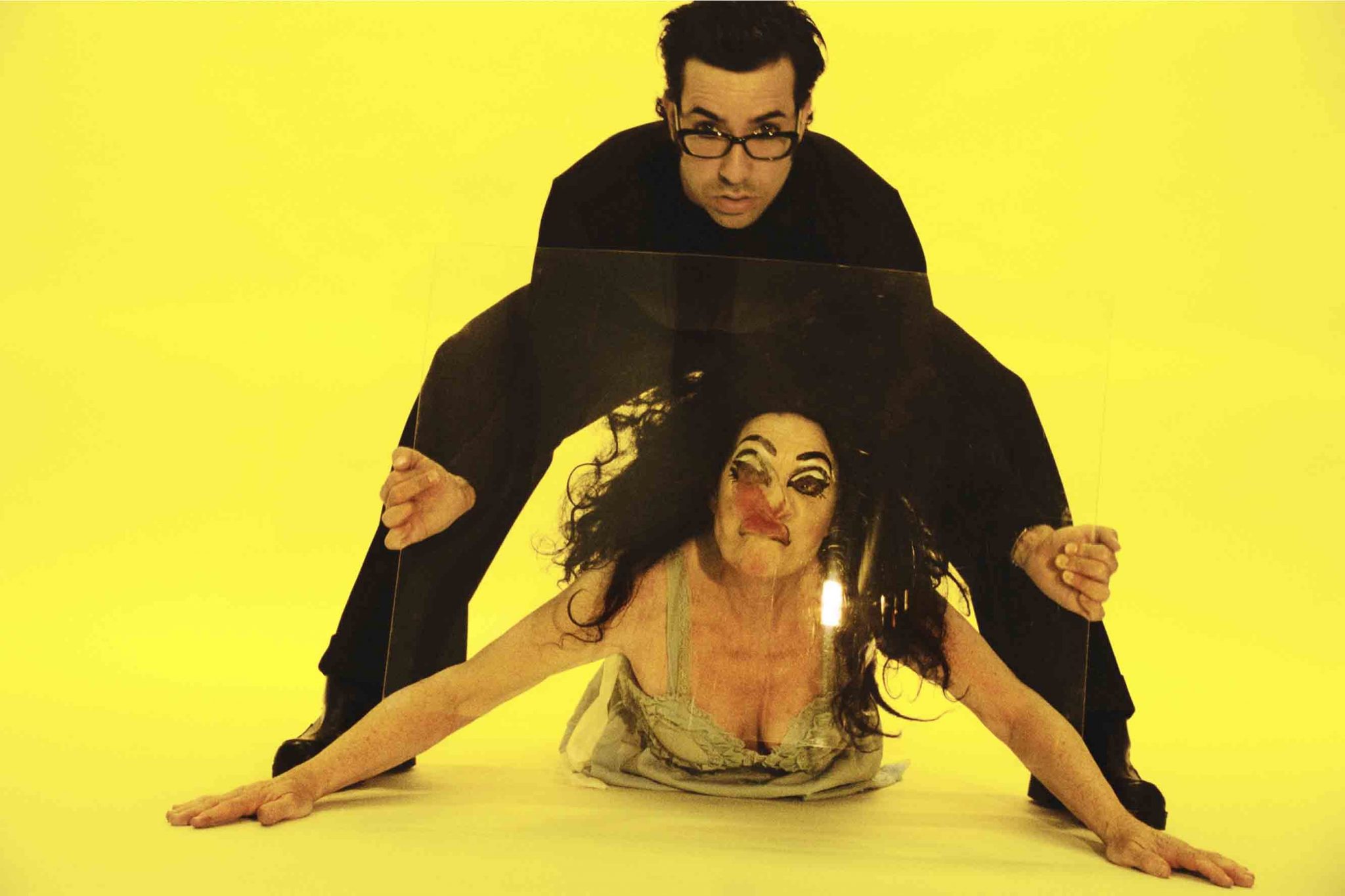

In this selection of works shot between 1997 and 2004, the first photograph as you enter the show, Facelift (1997), is a particularly nasty one. It shows Melee squatting over his prone mother, holding a sheet of glass that is pulling upward against her distorted, makeup-smeared face. The only studio shot in the whole exhibition (although of snapshot, not studio-print quality), it is the sole example to directly implicate the photographer. He peers with a measured gaze over the rims of his chic glasses in front of an ugly acid-yellow backdrop.

Knowingly camp, the artist’s stage wink is as heavyhanded as his mother’s pancake makeup. The all-too-obvious dig at an industry that preys on women’s fears of ageing seems like an alibi for the Melee family romance. This theatricality, with a heavy dose of dark body humour, defines most of the remaining works on show, which feature mother Melee like a demented drag queen who never makes it out of the bedroom (or toilet) and is too drunk to apply her makeup effectively.

The best images look like scenes from Old World fairy tales. As a monstrous sprite in Winter Solstice (2002), with black wig and a masklike face, she peers out from a snowcovered wood as if at the edge of an enchanted land. In Red Wig (2001), naked except for a beige-coloured back brace, she towers on straining tiptoes (like she’s wearing magically invisible stiletto heels) in a shabby, semiderelict room. The aged ghost of Francesca Woodman lurks in these rundown urban shadows, but this is a different kind of mythic creature, one with less nymphlike femininity, and the setting is lower rent. A harsh gash carved into the woodchip ceiling just above her head makes for a disturbing echo – Woodman-style – with the mother’s swollen labia central in the frame. Instead of fecund fruits, Melee gives us a hacked-out wound in a crass interpretation of pop-culture Freudianism.

Although Melee’s mother is the star here, she remains strangely elusive. It is the imagination of boyhood sexuality that comes through most vividly in both the magic and the horror of Melee’s photographs.

This article originally appeared in the October 2014 issue