During his 1996 party conference speech, Tony Blair famously said, ‘Ask me my three main priorities for government and I tell you: education, education and education.’ In part for the audacity of such a sentence – it sets out to identify three priorities for government and settles for one – and in part for the shift in focus that it at least ostensibly embodied, this line has entered the consciousness so much as to be instantly recognisable 17 years later.

On reflection, the sincerity of Blair’s sentiments is questionable. The former prime minister did preside over the introduction of tuition fees after a commitment to keep to Conservative party spending plans in the first term of office, and then a further rise in fees. Indeed it was Labour that commissioned the education review that led to the recent third rise in fees in the UK, to between £6,000 and £9,000 per year.

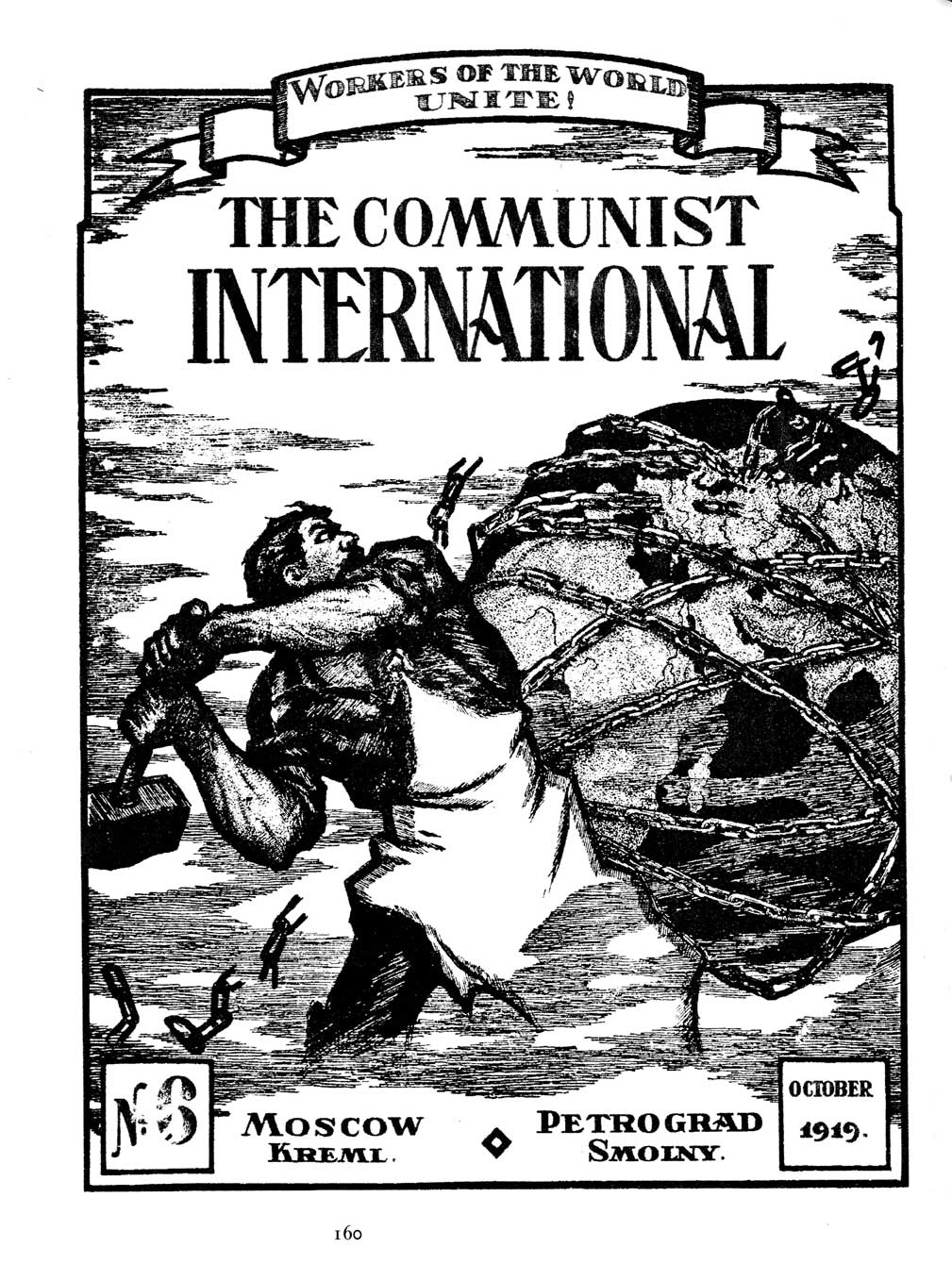

the artworld replaces the Communist International as a worldwide network and refuge for alternative thought

The corporatisation of higher education is a trajectory that crosses over party boundaries and has gained so much momentum as to be beyond challenge through conventional political channels. It is arguably for this reason that education has increasingly taken the centre ground in political and social discourse in the period since Blair made his famous speech.

Where education was once seen as a ‘soft’ policy area secondary in mainstream politics to economics, fiscal policy, foreign policy and law and punishment, it is now seen as fundamental to political discourse both at a mainstream and alternative level. This shift in focus is arguably motivated by two principal factors. Firstly, the final collapse of Soviet Communism during the late 1980s and early 1990s, followed by a massive collapse in the worldwide economy that started in 2007, and the inability of the political left to mobilise with convincing alternatives to capitalism in the intervening 17 years, has left us in need of new modes of thinking and new strategies for which our current knowledge base is clearly inadequate.

Secondly, while the academic left fails to provide convincing alternative social models, funding has been stripped in the UK – and this is increasingly reflected throughout Europe – from the subject areas that might most reasonably be expected to deliver those alternatives. We have a situation in which people need to get into debt to study a narrowing range of subjects that are increasingly reflective of the needs of industry. Taken to its ultimate conclusion, such a system will soon be lending money to as many people as possible to school them in the principles of the financial model which they will pay into when they graduate and begin to work in the interests of that same model.

the sum of human knowledge will become reducible to what is useful to the financial machine

With the nation state in the UK being hollowed out, emptied of its social responsibility and reduced to the position of a defender of the rights of the powerful without losing any of its power to enforce law and intimidate, it must fall to others to pose a viable alternative to the current system. In light of the diminishment of the state’s role, a nonstatist option must be prepared by the political left, regardless of whether individuals personally veer towards a statist vision of politics.

This is simply because, following the current trajectory, we will soon have a situation in which the state resembles little else than a malevolent giant guarding the palace against the hordes. Without an alternative to the values that it enforces through a mixture of instruction and coercion, the sum of human knowledge will become reducible to what is useful to the financial machine – the aforementioned ‘palace’.

What relevance does this have to art? Well, as Mark Fisher put it, talking at a conference entitled ‘Joan of Art: Towards a Free Education’, organised by myself and held at MACRO, Rome, in April of this year, the artworld in a sense replaces the Communist International as a worldwide network and refuge for alternative thought. In light of a convincing alternative existing in reality, it is left to the artworld to feign one: to grow an alternative within the empty husk left over from the dismantling of the state.

‘Joan of Art: Towards a Free Education’ was in residence with Gervasuti Foundation, Venice, for the duration of the 55th Biennale

This article was first published in the October 2013 issue.