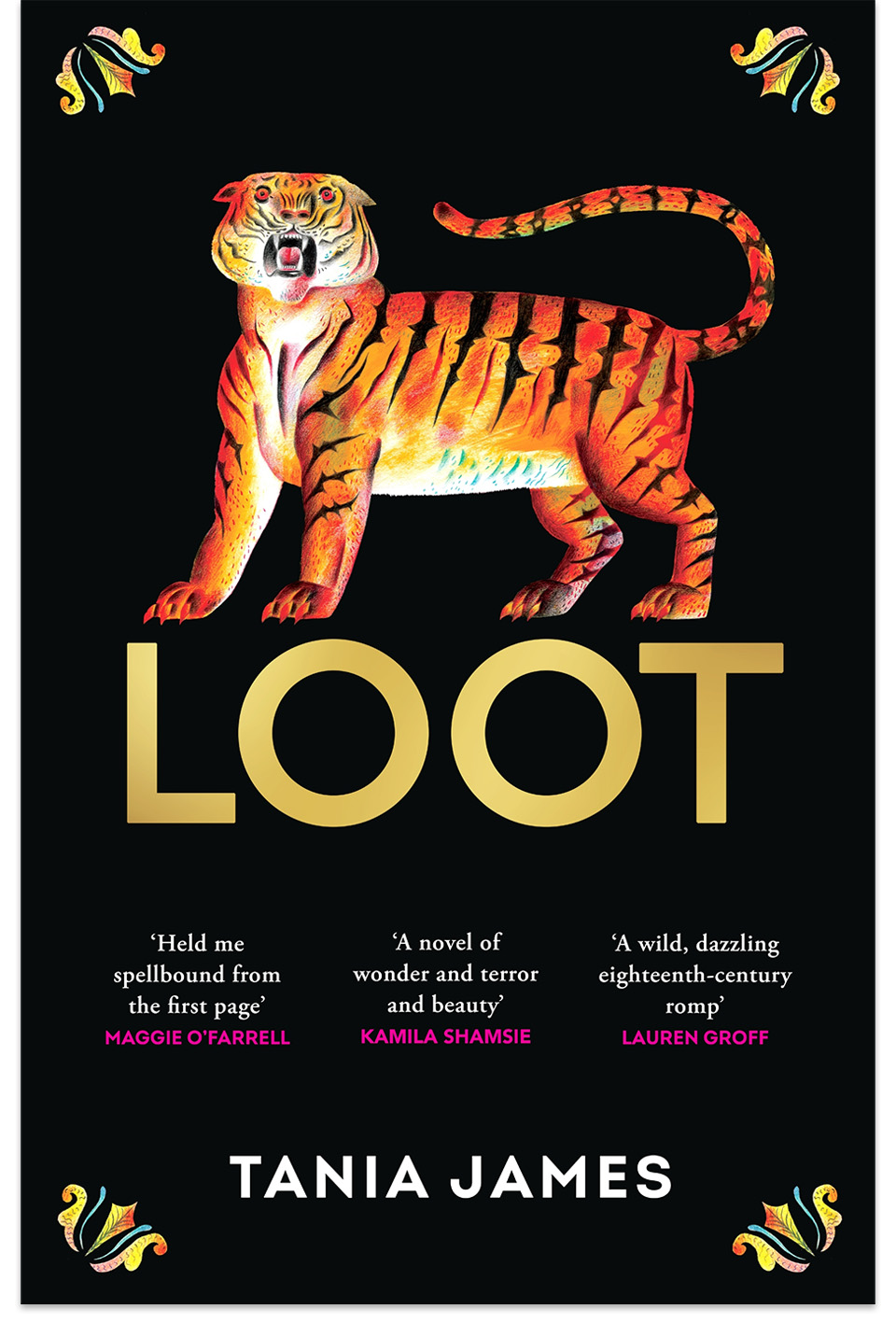

Tania James’s new book, Loot, which centres on an eighteenth-century tiger automaton, is part historical novel, part romance, part exposé of English attitudes to race and class

Tipu’s Tiger is a late eighteenth-century automaton, made for Tipu Sultan, the Muslim ruler of Mysore, presumably in celebration of his victories over the forces of the British East India Company during the Second Anglo-Mysore War (1780–84). Its makers’ names have been lost. When ‘played’, it depicts a near-lifesize European struggling and howling as a tiger mauls his neck. When the East India Company defeated and killed Tipu in 1799, it carted the automaton back to London as part of its extensive booty, describing it as a ‘memorial of the arrogance and barbarous cruelty of Tippoo [sic] Sultan’. Tipu would later feature in the original copy of the Constitution of India (1949) as one of the nation’s early freedom fighters; the automaton lies within a glass case in London’s Victoria & Albert Museum. It’s also the fulcrum around which American author Tania James’s latest novel turns.

Loot is part historical novel, part gesture towards colonial redress, part adventure story, part romance, part exposé of English attitudes to race and class. Part of its problem is that because of the overlapping thematics it never goes into any theme in any depth. But this messiness might also be its central truth, for the stories that are read into the Tiger are different depending on who’s telling them. Although we know that the reality of the Tiger’s tale remains that it’s told by the victors. As for the novel, it follows the fates of the imagined creators of the automaton, French clockwork specialist Lucien Du Leze and his local apprentice, the woodcarver Abbas. Lucien is ‘trapped’ in Mysore as his homeland is transformed by revolution making it impossible for him to return. Abbas comes from a lowly background and has been rapidly elevated thanks to his skill with the lathe. Their patron, Tipu, is in the last phase of his reign as the British noose tightens around his neck. All three are fighting for agency in a world that denies it to them. Their stories animate the Tiger in a way that goes beyond the historical object’s mechanical crankshaft and bellows.

Lucien makes it back to France; Tipu dies; the people inhabiting his fort at Srirangapatna are slaughtered; the city is looted; ‘prizes’ are distributed to soldiers (the Tiger goes to an English officer and aristocrat who chose it over gold and jewels to better satisfy the orientalist tastes of his wife); Abbas barely survives and follows his creation to England, managing also to fall in love with Lucien’s adopted daughter, the mixed-race, but white-passing Jehan; the officer’s wife, it later turns out, has a sideline in erotic and exotic literature, having churned out her own, semiautobiographical version of Aladdin; she’s having a (necessarily) secret relationship with her husband’s sepoy assistant, his master having died before he left India; while Abbas, aided by Jehan, is determined to repossess his creation as proof of his skill and existence. ‘Behind each imperfection’ in the Tiger, we are told, ‘is a story only he [Abbas] would know, a story interwoven with his own.’

The problem, of course, is that almost every character that encounters the Tiger has a story of their own to tell too. Even an apparently simple word like that of the book’s title has multiple interpretations. To the British aristocracy, ‘loot’ is a card game (a version of ‘snap’), while to people like Abbas it’s a form of theft, and to organisations like the East India Company Tipu’s Tiger is both a reward and a helpful form of justification for violence and exploitation. What we learn in the course of James’s narrative is that, in the battle of who gets to tell their story, class trumps truth, and race – ‘the final ranking’ – trumps class. In this, the author is self-consciously indebted to the twentieth-century Sri Lankan leftwing intellectual Ambalavaner Sivanandan, who was director of the London-based Institute of Race Relations between 1973 and 2013. Towards the end of the novel, she deploys an adapted version of his celebrated statement about postcolonial migration – ‘we are here because you were there’ – although perhaps the truer summary of the novel is contained in another of Sivanandan’s catchphrases: ‘If those who have do not give, those who haven’t must take’.

Loot by Tania James. Harvill Secker, £18.99 (hardcover)