Rirkrit Tiravanija’s 2022 Okayama Art Summit, Do We Dream Under the Same Sky, continued the artist-led experiment in a show that was both physically compact yet intellectually expansive

When it was launched back in 2016, Okayama Art Summit’s USP was that it was ‘an experiment directed by internationally renowned artists’: British artist Liam Gillick for the inaugural edition; Frenchman Pierre Huyghe in 2019; and now Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija. (That all three have, at various times, been tagged as members of a gang who came to prominence through producing ‘relational’ art may constitute an overarching theme for the project.) Select works from those two previous editions pepper the city: among them Peter Fischli and David Weiss’s readymade How to Work Better (2016), a ten-point list (do one thing at a time; know the problem; distinguish sense from nonsense; say it simple; etc) the duo appropriated from a sign on the wall of a ceramic factory in Thailand, enumerated here down the side of a tower block; and Lawrence Weiner’s text work BLOCKS OF / COMPRESSED GRAPHITE / SET IN SUCH A MANNER / AS TO INTERFERE / WITH THE FLOW / OF NEUTRONS / FROM PLACE / TO PLACE (2017, from the 2019 edition) that cascades down the facade of the bunker-like Cinema Clair. You can take that as proof of either the project’s legacy or of the city’s submission to the language of art. Although as the evidence just cited indicates, that language is English.

Of course, after a decade of artist-led Kochi-Muziris biennales and last year’s Documenta (directed by art-collective ruangrupa) and Berlin Biennale (helmed by artist Kader Attia), that initial SP now seems a little less U, but the idea of the exhibition as a form of experiment, and the exhibition as a form of dialogue and forum for discussion (suggested by the somewhat curious ‘Summit’ branding), persists in a show featuring work by 27 artists and groups at ten sites physically compact (you can comfortably get around it on foot and in the space of a day) but intellectually expansive.

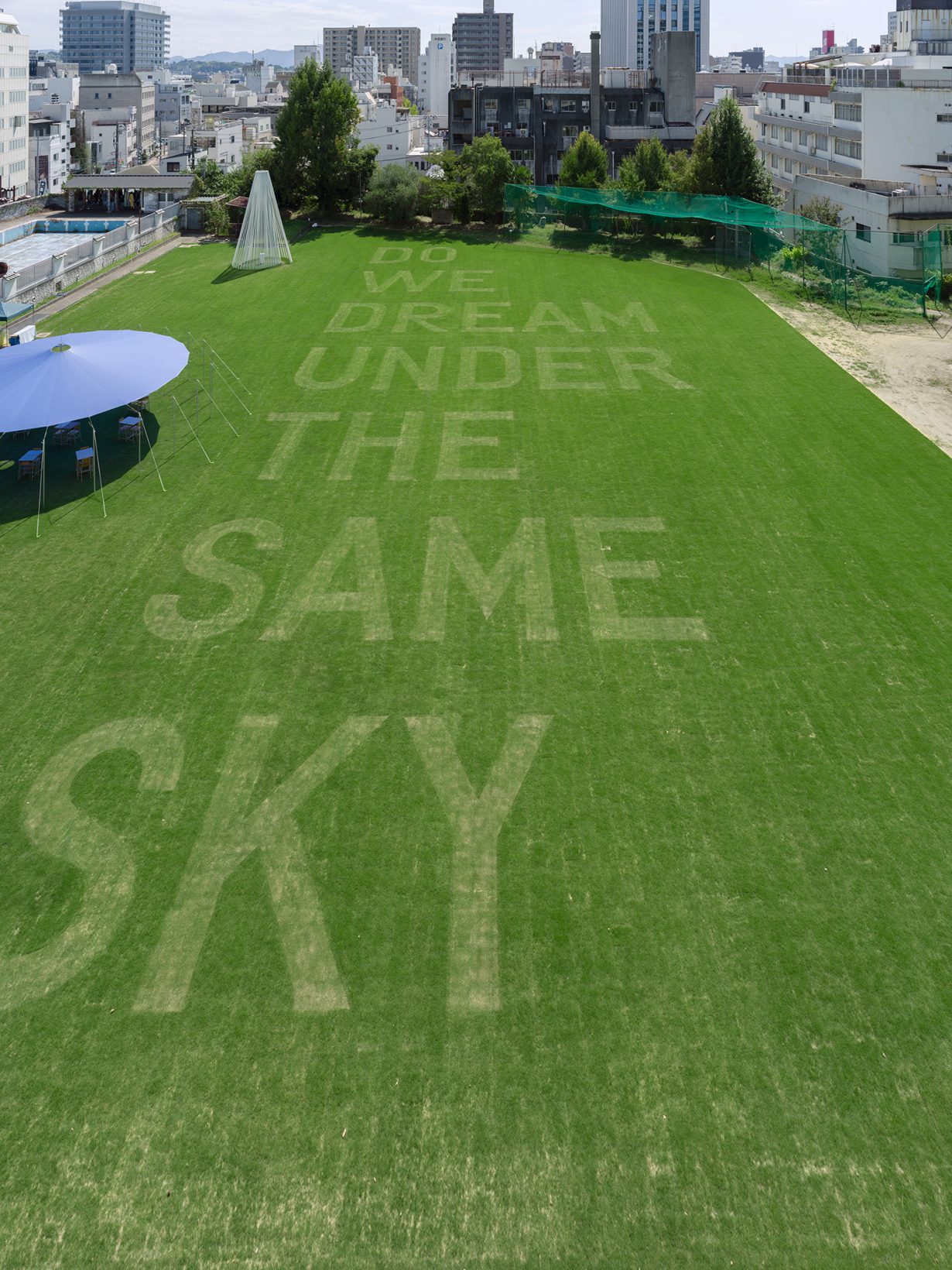

Indeed, that Do We Dream Under the Same Sky follows in the tradition of what has come before is implied. After you’ve passed the Fischli & Weisses and the Weiners, the title of this year’s summit, also a work by Tiravanija, is, like the previous works, written into the fabric of the city (inscribed on the lawn, outside one of the triennial’s primary exhibition sites, the former Uchisange Elementary School). Although perhaps, in this case, the grass cutting indicates a concession to a certain amount of contingency and ephemerality.

In his curatorial statement, Tiravanija frames the exhibition’s title, which hovers somewhere between a question and a proposition, as ‘an opening to an idea’. An idea that the artist has been exploring in various ways (installations, books, etc) for the past several years. Here that idea crystallises in the suggestion that what’s on show represents something shared but potentially different, which you might argue is the basis on which most art, of any time and from any place, is founded. But the obvious is not always connected to the straightforward. While many of the artists on show here work in the West, the majority articulate concerns and concepts derived from elsewhere. Frequently as a result of personal or family migration or a diasporic heritage.

So, beyond the usual curatorial babble, what does that mean?

Over to the Orient Museum, where, among the Roman, Byzantine and Assyrian collections (which leaves you more than a little confused about what ‘Orient’ means here – west of Japan?; all the way east but skipping over North America? Or perhaps simply an unhelpful use of European terminology or museology?), sits Rasel Ahmed’s 18-minute, two-channel video Who Killed Taniya? (2020). On the face of it, the video simply records a group of drag queens applying costume, makeup and prosthetics (at an underground drag show in Dhaka, capital of the artist’s native Bangladesh). Ostensibly the theme of body image is one that finds echoes in Mari Katayama’s photographic self-portraits back at Uchisange. (Katayama is a double amputee.) But, just as with Katayama’s works, the text that unfolds alongside the imagery in Ahmed’s video explodes any idea of a simple reading: it evokes the nature, status and anxieties attached to being labelled a refugee. Following a short digression on joint attention theory, a certain amount of self-consciousness (‘is this a documentary or a makeup tutorial?’ the text asks at one point) questions what makes us different and what makes us belong, whether or not that last is objectively observable, the uncertain relations between truth and fantasy, and notions of authenticity. If you subsequently find out that the drag show’s lead performer was killed in an Al Qaeda attack two months after the film was shot (originally as part of a personal archive) and that the artist, at the time best known for founding Bangladesh’s first LGBTQ magazine, was forced into exile after the magazine’s publisher was hacked to death (for which the nation’s home minister blamed his involvement with a ‘homosexual’ publication), the shockwaves ripple even further.

Similarly, Vandy Rattana’s sublime The MONOLOGUE Trilogy (2015–19), at Uchisange, comprises videos presenting a series of apparently straightforward rural scenes (jungle, fields, landscapes) that are complicated by contextualising monologues (in Khmer – English is not necessarily the dominant language in this exhibition, although there are subtitles here) that accompany them. In the first video, titled MONOLOGUE (2015), the field, in the middle of a jungle, turns out to be the probable, but not necessarily exact, site at which the artist’s sister’s (and grandmother’s) bodies were buried in a mass grave by the Khmer Rouge. The land itself bears no trace of this; just as, via his monologue, the artist is left to imagine (or dream about) the sister he never really knew; even though they were both, at different points, present under this same sky.

It goes without saying that Tiravanija’s conceit neatly ties many of the elements of his exhibition together without feeling heavy-handed, such as to force one particular reading over another. A group ‘index’ show (within the bigger show) collects works by every participant in the art summit (generally unrelated to the work each is showing elsewhere) into a kind of discussion forum (or artistic director’s mixtape), but, curatorially, the show is tight rather than suffocating. In the toilet of a tiny downtown Italian joint, I stumbled across one of a series of pencil portraits of Tiravanja executed by Yutaka Sone (who, elsewhere, was performing a spoken-word poem with a Japanese drone band on top of a makeshift-looking oil-drum stage designed with Tiravanija and made of marble) and donated to local restaurants in which the pair had dined. “Only available wallspace,” the owner explained apologetically, handing me a brochure for the art summit as I walked out.

Indeed, if the remnants of previous editions of the summit suggest a focus on the West, Tiravanija’s edition toys more evidently with the local. Not least through the inclusion of Shimabuku’s video Swan Goes to the Sea (2012/14), which features the artist taking one of the swan-shaped boats available to tourists and pleasure seekers at Okayama’s Asahikawa riverbank out for a longer trip. Shimabuku, whose mother is from Okayama and went to school at Uchisange (where his work is now installed), created the video having sailed the boats as a child, finding them still there when he returned 40 years later as an adult. The resulting video is at once ridiculous, liberating, cathartic and nostalgic.

The more general mix of the playful and the innocent with the sombre and the disturbing is repeated next door to Tiravanija’s grass-writing back at the former school. Precious Okoyomon’s Touching My Lil Tail Till the Sun Notices Me (2022) features a wide-eyed, massively oversized, plush brown teddy bear, girlishly clad in translucent white underpants and a pink hair-band, spreadeagled in a drained and dirty, weed-covered swimming pool, pink tongue poking out of its mouth and sightless eyes looking skywards. As if it had passed out in the middle of some form of schoolgirl cosplay. Next door to the bear is a rail featuring a selection of garments designed by Overcoat (a New York label founded by Japanese designer Ryuhei Oomaru), each of which is decorated with Tiravanija’s slogans ‘No More Reality’, ‘Tomorrow Is Another Day’, ‘Fear Eats the Soul’. Just in case you feel like getting in on the cosplay too.

The 2022 Okayama Art Summit was on view from 30 September to 27 November 2022.