Two weeks after the devastating fire in Tai Po, it’s clear the fault lies beyond Hong Kong’s iconic plant

In late November, as the horrific fires at the Wang Fuk Housing Estate in Hong Kong’s Tai Po area were still burning, a distant but loud jury on international media and social media accounts was already pointing fingers and saying: it was the bamboo. At least 159 people had been killed, the destruction still ongoing, while the chorus grew: ‘The bamboo scaffoldings must go, look what they have done. Hong Kong, it is time you got rid of your bamboo.’ Judged like a vestige of pre-civilised behaviour, unfit for modern times.

While a stunned and traumatised city prayed that the firemen could extinguish the flames as fast as possible, and save the surviving residents, people went online with flamethrowers and pieces of bamboo to show that no, try as you might, you cannot set bamboo ablaze. But it was already too late: even now, much of the international media depicts the devastation in Tai Po with what sounds like a sneering tone: tragic and strange how such a modern city could be so backwards, with its fire-prone bamboo sticks.

Tai Po burned down, the bamboo was blamed, and it was like two tragedies in one fell swoop. Hong Kong and bamboo go hand in hand: near Tai Po, as several other places across the city, there are particularly rich bamboo forests. But walk anywhere, really, and you will see bamboo. In the scaffolding covering buildings all around urban areas, sometimes even just a little bamboo balcony perked high on a building facade for renovating a flat. There are intricate castles, feats of engineering that have been built at amazing speed by the local spidermen: zizyuhaap, in Cantonese, which literally means spider martial artists. You don’t become a zizyuhaap in a day. It takes years of training, and then these aerial acrobats are subject to a hierarchy that allows new spidermen to fully lead a project only after three months spent up in the air tying bamboo.

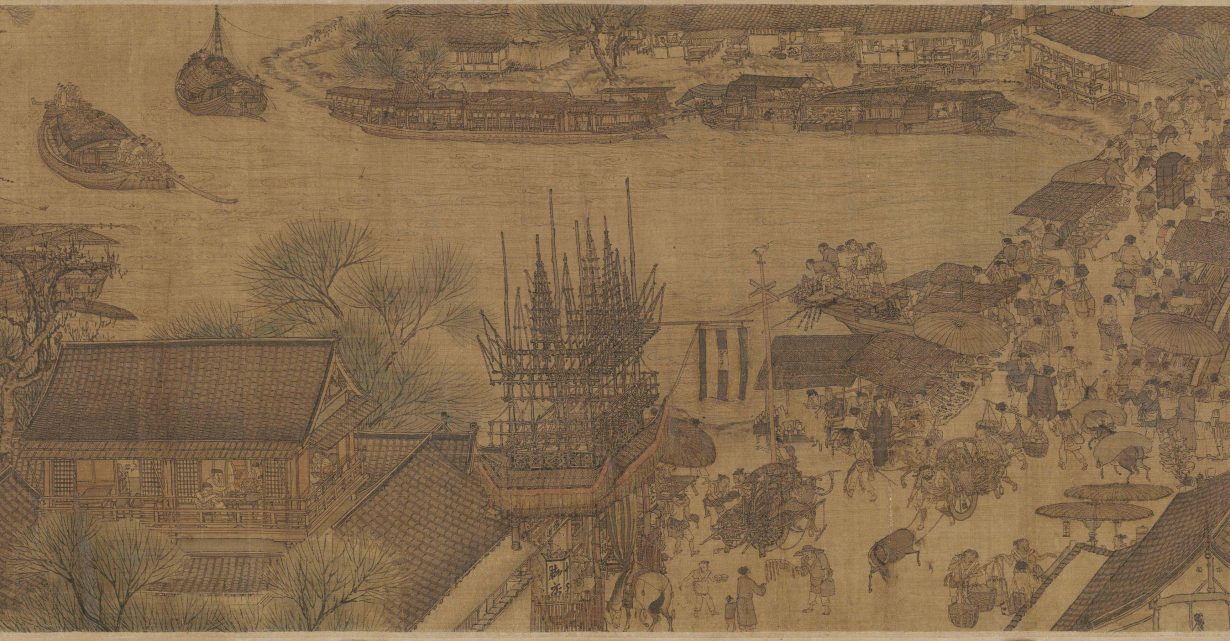

Bamboo also grows in every park and in every country park, on every path in rural parts of the territory – walk past it when it is windy and you can hear them squeak, speaking their own bamboo language. Bamboo, botanically speaking, is not a tree, but a type of sturdy, tall grass, and it is part of the Gramineae family. There are around 60 different species commonly found in the city, but only two types are used in scaffolding: Kao Jue, or pole bamboo, and Mao Jue, or hair bamboo. The latter is thicker, stronger, has a diameter of around 75mm and is used for bearing loads. The first one is thinner, lighter and employed for platforms. Before putting it to use for the construction industry, bamboo is dried for about three years and coated in a flame-repellent material. It will be cut to standard size (seven metres for simple scaffolding, which is then easy to cut further and adjust as necessary) and stored in the open, good to reuse about three times, and then left to return to nature. Bamboo is ubiquitous, yes, but most importantly flexible, light and flame-retardant. It has been used as a construction material for thousands of years all over China – one of China’s most famous paintings, a 5m-long Song dynasty handscroll now in Beijing’s Palace Museum, titled Along the River During the Qingming Festival, most likely by Zhang Zeduan, is often cited in this context. It shows a remarkably lively scene of street life in today’s Kaifeng (known as Bianjing during the Northern Song, 960–1127 CE), going from the city centre to its rural areas, and it has a bamboo scaffolding right in the middle, where what looks like a temple, or a mansion for a wealthy person, is being built. Today, bamboo is mainly used in Hong Kong, where it has become one of the many markers of a too-frequently threatened identity. Lap-See Lam, a Swedish artist of Hong Kong descent, built a bamboo scaffolding for the Nordic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2024. Even for second generation diaspora, bamboo has an emotional meaning that pulls endlessly.

Five days after the fire, the local authorities declared that while the origin of the fire was still unknown (a welding spark, or maybe a cigarette), the bamboo was not to blame. The inferno was caused by cheap, flammable netting, which had been draped on the building’s scaffolding after one of the strongest typhoons to hit Hong Kong this year destroyed the existing netting, as well as the polystyrene foam board with which the renovation company had covered the buildings’ windows. It also surfaced that residents had complained about both the Styrofoam and the netting, saying that they felt unsafe. Corner-cutting, indifference and probable corruption (and can we say, in this case, greater emphasis and man-hours put on ‘safeguarding national security’ instead of citizens’ security?) are the cause of this disaster, not Hong Kong’s iconic plant. Not bamboo-made: man-made.

Read next ‘Restorative Justice’: Beirut’s Struggle with Truth