Fuzzy blocks of white and blue melting together on a horizon of smudged curlicues; a Nicolas de Staël beach scene in soft focus; Mark Rothko illustrating a package holiday brochure; an impossible smear of mottled landscape beneath a Jean-Francois Millet sky; an uncertain figure centre-frame resembling a horse made of smoke rearing triumphantly at nothing in particular; spiked Albert Oehlen-esque puddles in bright, burnished orange against a field of gradient fill pinks and blues, like the gaudy sign of a seafront restaurant written in some hitherto unknown East Asian script; Duchamp in his cubist phase illustrating some kitsch nineteenth century grand opera in a scurrying of deep purples, yellows, and blues; three vertical slashes of mauve, shimmering in the heat haze; a drunken fight in a stained glass workshop.

These are just a few of the images produced by the Creative Adversarial Networks (CAN) software model, a ‘computational creative system for art generation’, as the paper from Rutgers University, the College of Charleston, and Facebook Artificial Intelligence Labs puts it, ‘without involving a human artist in the creative process’. It’s art made by AI, a machine for the production of ‘new styles’ and ‘new ways of expression’.

more respondents saw the touch of human hands, the spark of human genius behind the AI-generated images than the Art Basel pictures

If you thought I was simply describing the canvases lining the walls of a mid-tier booth at Art Basel, you’re not alone in your confusion. Seeking validation, the CAN team crowdsourced a panel of judges from Amazon’s online task marketplace Mechanical Turk and had them compare the generated images with established works by real artists. The panel had little trouble discerning man- from machine-made when comparing the CAN images to a sample of 25 abstract expressionist masterpieces. But faced with a random swatch from the aisles of 2016 Art Basel art fair, the judges struggled to differentiate. Finally, more respondents saw the touch of human hands, the spark of human genius behind the CAN set than the Art Basel pictures (by 53% to 41%).

The CAN process is twofold, consisting of two opposing software agents. A ‘generator’, working from a purely random input, without access to any previously made artworks. And a ‘discriminator’ which compares the generated images to an existing dataset of artworks. Comparing the new algorithmically-generated works to an established catalogue of some 81,000 paintings by 1,100 artists from the fifteenth to the twentieth centuries, the discriminator asks first, is it art? And second, is it new? Does it correspond to any ‘established style’?

CAN’s discriminator recognises ‘established styles’ from Rococo to Nouveau Réalisme, Cubism to Colour Field painting. It’s your Art History BA in chip form. If the new image scores a ‘yes’ from the first question and a ‘no’ from the second, then it passes muster, qualifying as a novel work of art unsullied by human intervention. The CAN team, evidently, have created not only an artificial artist, but also an artificial art critic. (If they can only come up with a way of automating galleries and collectors as well, then we humans might cheerfully leave the entire art world to its own devices.)

The theoretical justification for the CAN approach comes from a book by Maine psychology professor Colin Martindale published in 1990 called The Clockwork Muse. Martindale set out to discover an objective science of artistic novelty. In fact, he assumes that creativity is deterministic from the off and states it baldly on his third page. The Clockwork Muse, in fact, is a completely insane book. The author insists from the start that social and political factors can have no influence on the general thrust of artistic development. ‘Facts,’ Martindale proclaims, ‘have to be completely distorted if you wish to say otherwise.’ Only the internal aesthetic forces of ‘habituation’ to a given form and renewed ‘arousal’ by fresh novelty may drive art history in Martindale’s system.

it wants images that are original enough that they can’t easily be categorised, but not so original that they freak people out

Since Martindale himself is aroused solely by numbers, he tests his hypothesis quantitatively, measuring the arousal produced by different historical works. But when his analysis of the development of Italian music over the last few centuries fails to match his expectation of a smooth rising curve, he simply declares that ‘what has heretofore been referred to as Italian music is not music at all.’

Such methodological peculiarities notwithstanding, Martindale’s gist is that people, in general, prefer ‘somewhat novel things’ – deviation from what we’ve seen before, but a manageable level of deviance. A kind of Goldilocks middle-ground of the imagination. Hence CAN’s two-tier grading – it wants images that are original enough that they can’t easily be categorised into some prior movement or style, but not so original that they freak people out.

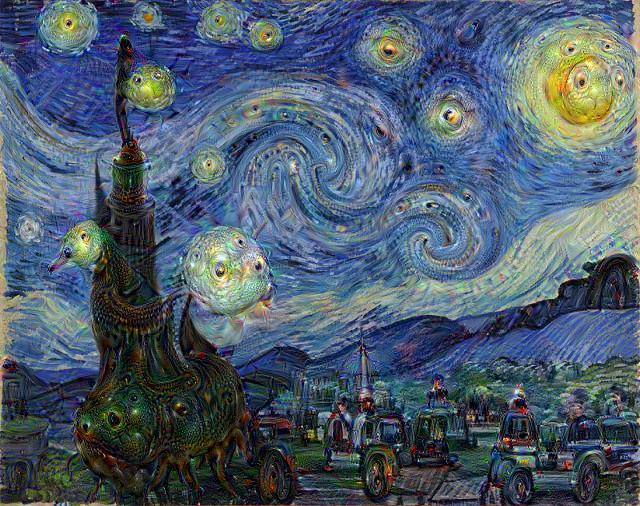

The CAN project is just the latest in a swelling tide of AI art projects. Since publishing their open source code in July 2015, Google’s DeepDream project has been wowing your Facebook friends with their uncannily cute dog heads emerging out of psychedelic neon swirls. Working like facial recognition software in reverse, DeepDream recognises and draws out familiar forms in a given image background, even when there was no trace of those forms there to begin with, producing nightmarish digital phantasmagorias by a kind of algorithmically-enhanced pareidolia. More recently, Google research scientist Douglas Eck announced Magenta, an ongoing research project seeking generative models for art-making with a focus on making something genuinely compelling, and not merely diverting.

The lurking presence of tech giants like Google behind so many such projects may well indicate a burgeoning anxiety in Silicon Valley. Google platforms like YouTube and Blogger depend on other people’s creativity to draw in attentive eyeballs that can be sold to advertisers. But when content creators start demanding recognition – and even remuneration – for their labours, executives must start to question whether they might be able to find a workaround. With the presence of Facebook’s Mohamed Elhoseiny on its team, the CAN project is, in this sense, little different. But in other respects it sets itself strikingly apart. It requires no manmade image as a starting point and needs no human guiding hand to steer it. It promises a perfect closed system, capable of churning out images ad infinitum– each one ‘novel’, but not too much.

What are we to take from CAN’s success at fooling its jury, from its apparently limitless creative potential? That the software possesses true artistic imagination and deserves recognition, a glossy Phaidon coffee table book, and perhaps a seat at the Royal Academy? That the technological Singularity is here and artists and critics alike might as well hang up our pencils now to retrain as carers, coders, or cattle farmers? Or something more worrying?

What the researchers have performed is essentially an aesthetic version of the Turing Test, Alan Turing’s notorious ‘imitation game’ of 1950 that asked a human subject sat at a computer terminal to judge whether their onscreen interlocutor was human or machine. Over the past few decades, Turing’s test has been passed numerous times by relatively unsophisticated chatbots following predetermined scripts. Each victory proving little about ‘machine intelligence’ and rather more about the standard of conversation one might expect from a total stranger, conducted via typing words into a computer terminal. Given that these are precisely the circumstances under which we all conduct a significant proportion of our daily conversations, the success of bots like ELIZA, PARRY, and Eugene Goostman might also say something about the anomic nature of life in the twenty-first century.

Likewise the nature of contemporary art reception.To suggest, as CAN’s developers seem to, that creative ‘style’ and artistic ‘newness’ can be reduced to a different arrangement of colours on a page strikes me as a misunderstanding of what it is that artists today do, and have done for as long as there have been non-figurative 2D works called ‘art’. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, the work performed by artists has been much less about simply arranging so much paint on a canvas or so much stone on a plinth and much more about finding new ways of seeing and understanding the world. If this was recognised and to some extent formalised by the conceptual artists of the 1960s, it had demonstrably been true already for several decades by then. That there remains plenty of real human artists today who nonetheless make careers out of more-or-less anonymous, more-or-less decorative colour fields, oil flecks, and acrylic splotches should vindicate neither the researchers, nor the artists in question. Glancing through the works by Ma Kelu, Panos Tsagaris, and Cenk Akaltun in the researchers’ Art Basel image-set it’s not hard to imagine how their quasi-arbitrary forms and just-daring-enough advances on the familiar might be mistaken for the work of an automata. Suffice to say that, having been presented with such an abstract swirl of colours on a computer screen, feeling the urge to respond, ‘Yes, I can imagine seeing that on display at Art Basel’, might not always be a compliment.

feeling the urge to respond, ‘Yes, I can imagine seeing that on display at Art Basel’, might not always be a compliment

Interviewed by Rhizome’s Thomas Beard in 2008, American artist Guthrie Lonergan spoke of an “internet aware art”; work made in full awareness that its online reproduction will circulate far more widely than the thing itself. Those who have followed Lonergan in making work that draws the question of its networked dissemination into the conceptual apparatus of the work itself may well be flattered to be mistaken for the work of a machine. For those others, tarrying in a ‘zombie formalism’ whose thin veneer of organic life is now belied, a change of priorities may be prompted. The evidence from the history of the (standard, dialogic) Turing Test, however, suggests that on the contrary the direction of travel is towards human modes of communication evermore machine-readable.

For my part, it is the CAN project’s failures that pique my curiosity, those images dismissed – by observers either human or machine – as outside the bounds of art as we know it. In those strange new worlds where no-one has gone before might be the stirring of some new life to be animated by new forms of collaboration between humans and machines. To do so might involve the overthrow of ‘discriminators’ built both of silicon and flesh.