The first living artist to solo at London’s The Courtauld Gallery, Doig presents in his paintings a series of beguiling, fugitive, oddly mournful visions

Peter Doig is the first living artist to be granted a solo exhibition at the Courtauld since its 2021 refurbishment, and the institutional logic of this isn’t hard to grasp. Passing through the gallery’s immaculate permanent collection – with its Manets and Monets, its Gauguins and Cézannes – visitors arrive at two rooms containing 11 canvases by the Scottish painter, accompanied by wall texts emphasising the impact the big guns of Impressionism and Postimpressionism have had on his work. The aim seems to be to charge the Courtauld’s holdings with an aura of contemporary relevance, while simultaneously performing a kind of art-historical hazing ritual. For anybody who feels, like me, that all this is deeply unnecessary (of course the past speaks to the present, of course Doig is already by broad consensus one of the key painters of his time), the best approach is to ignore it, and focus on the beguiling, fugitive, oddly mournful visions the artist summons from his paint.

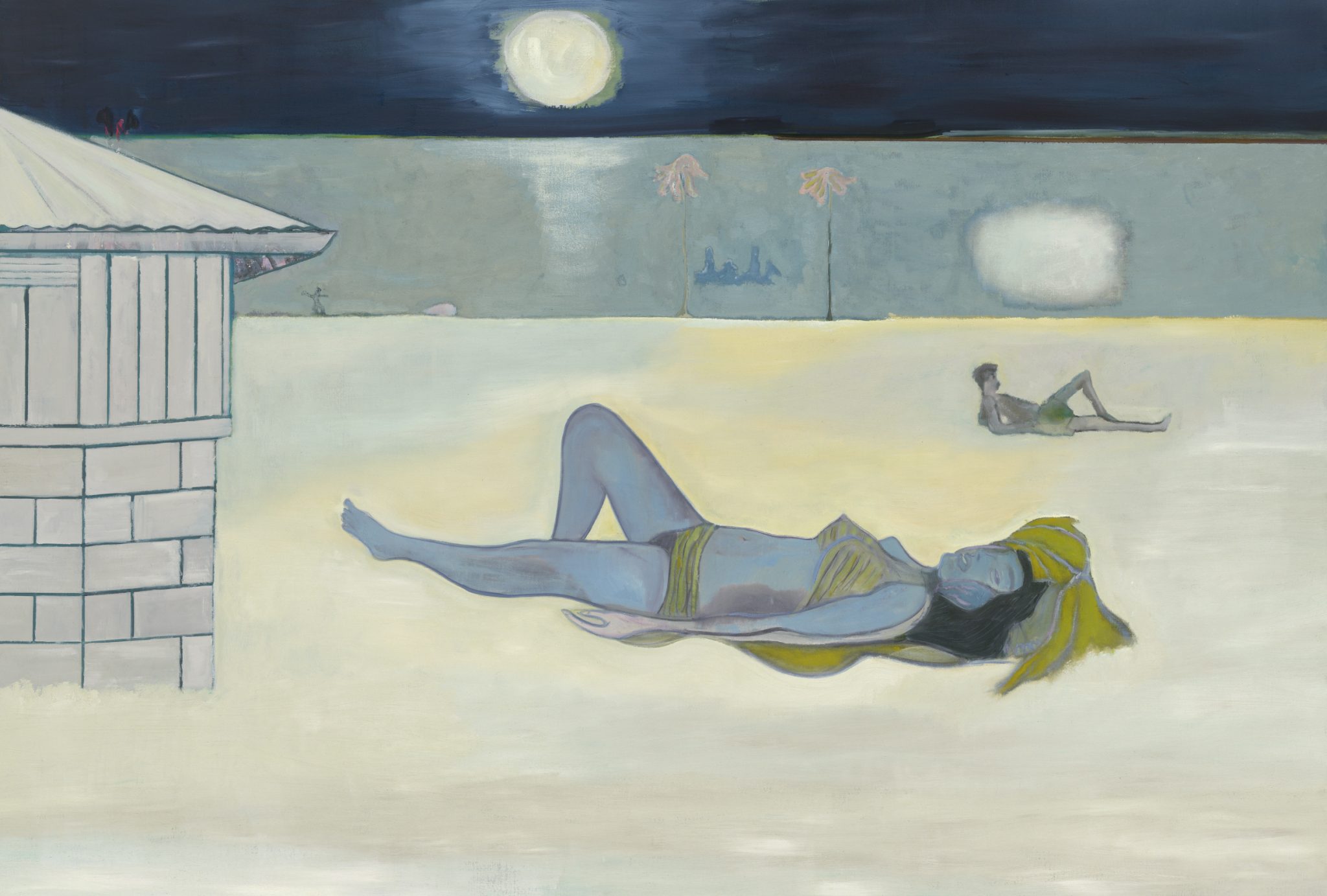

Doig worked on this set of canvases before and after his recent move back to London from Trinidad, where he spent his early childhood and was based for the last two decades. If his show has an overriding theme, then it’s the experience of time and place, and how they’re distorted by the interior stuff of memory and mood. The setting for Night Bathers (2011–19) is Maracas Bay, one of the Caribbean island’s most popular beaches. Spaced far apart on the lemony sands, a man and a woman stretch out not beneath a blazing sun, but under the cold flattening light of a full moon, while the still, grey-green sea glows with phosphorescent algae. This sense of a world askew persists in Music Shop (2019–23), where a musician in a skeleton costume looms outside a second-hand-instrument store, hefting his guitar like the Grim Reaper’s scythe. This is the late Trinidadian singer Shadow, and looking past him through the barred windows of the shop, we see that its merchandise has been replaced by views of a distant island. Is this an image about music as a gateway to a greater communion with place, or is Shadow a Charon figure, ready to ferry us towards the afterlife?

Another nocturne, Painting on an Island (Carrera) (2019), depicts an artist seated by a seawall, dragging a brush across a densely blackened canvas, although whether he’s effacing or further intensifying its darkness remains unclear. His bowed head – a riot of impasto paint, part curls of hair, part brain matter – echoes both the moon dipping below the horizon and a faraway landmass jutting from the sea. The titular island of Carrera, we should note, is a Caribbean penal colony, and the labouring artist is likely an inmate. Freedom, it seems, is where we find – or imagine – it. Modelled with Cézanne-like perpendicular brushstrokes, the pale colossus who poses awkwardly in Bather (2019–23) is based on a swimsuit shot of the American actor Robert Mitchum, who filmed the movie Fire Down Below (1957) on Trinidad and later released a calypso album. Maybe this uneasy figure is a proxy for the artist, another white man who found himself inspired by this island, a place shaped by the legacies of colonialism and slavery.

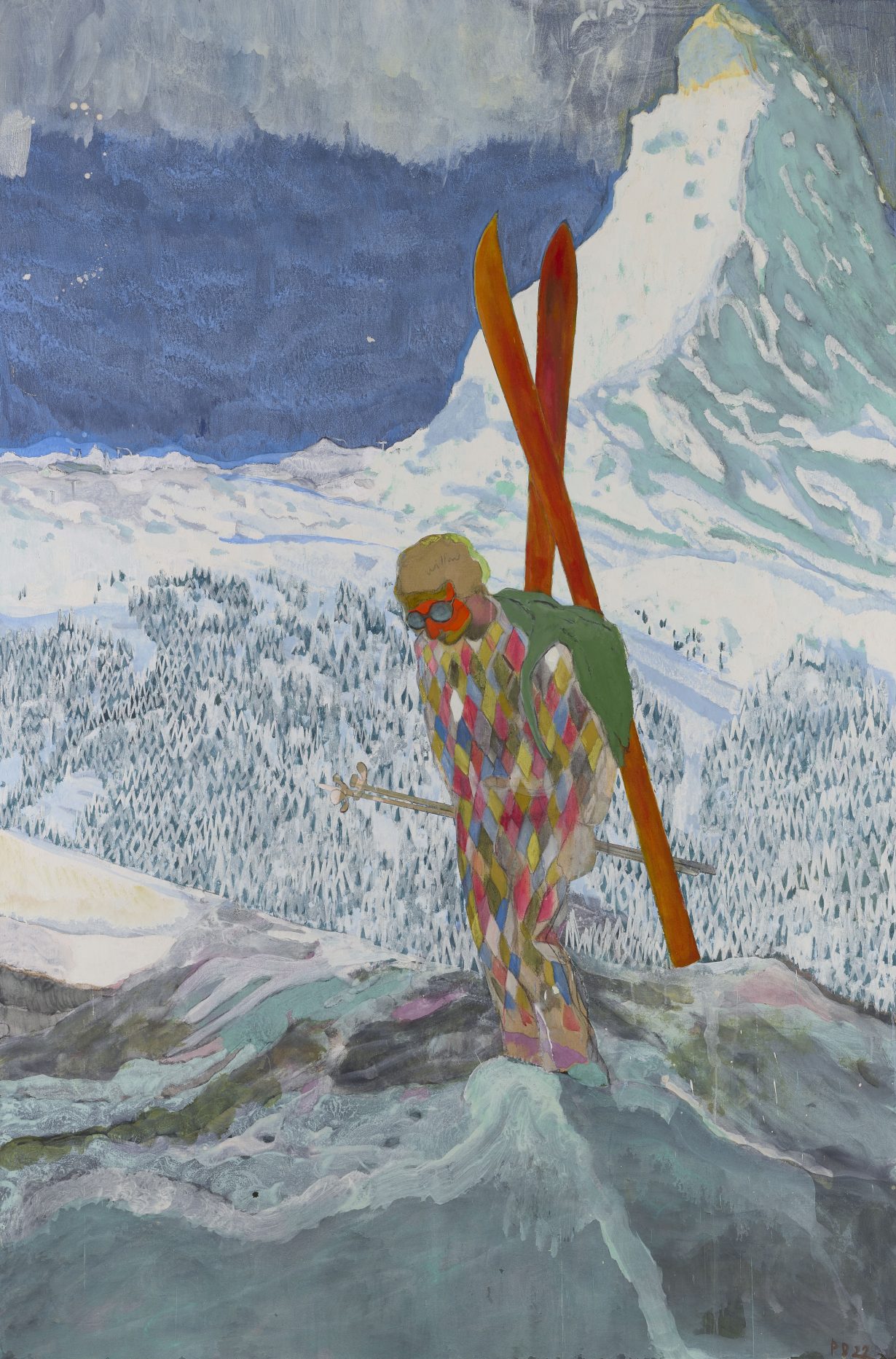

Canal (2023) sees Doig return to London, although this ghostly image of the artist’s young son eating fried eggs on a towpath beside a fiery red bridge feels temporally unmoored by two framing banks of trees, one dotted with spring blossom, the other heavy with autumn leaves. It’s as if the present were collapsing into a half- remembered past. In the show’s best painting, Alpinist (2019–22), a skier in a Picasso-esque harlequin onesie ascends a lonely mountainside, recalling at once Caspar David Friedrich’s imperious Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818) and the trudging peasants in Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Hunters in the Snow (1565). His face sun-burned a synthetic soda-pop orange, he bears his skis on his back like a crucifix. The scrawled letters on his helmet might read ‘Vuillard’ (a reference to the Nabi painter, Édouard?), or perhaps ‘Will end’. Beneath his feet, a glacier melts into gorgeous, deadly slush. It’s a work about burdens that feel by turns weightless and near-insupportable: history and talent, hunger for life and the inescapable fact of death.

Peter Doig at The Courtauld Gallery, London, through 29 May