Is it still possible to present Picasso and avoid the obvious criticisms?

Word has it that some members of the Hong Kong public don’t appreciate how Picasso for Asia – A Conversation, which comprises over 60 Picasso masterpieces loaned from Musée National Picasso-Paris, presented alongside works by 30 Asian and diasporic artists in the M+ Collections, can open with anything but an artwork by Picasso. Others are asking if Asia needs another Picasso show at all, when artists such as Isamu Noguchi or Wifredo Lam deserve canon-expanding surveys that speak to new generations. Everyone has a point.

Zeng Fanzhi’s Picasso (2011), installed on a wall at the entrance, acts as a prologue. In it, Picasso appears like an apparition, cigarette in hand, with strokes on unprimed canvas scratching upwards from his head and dripping down from his black-trousered thighs, recalling Francis Bacon’s ominous 1953 Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X. Whether Zeng had this reference in mind or not, Picasso’s gaze feels menacing. He was, after all, a powerful, extractive and arguably overhyped man: that much has been established.

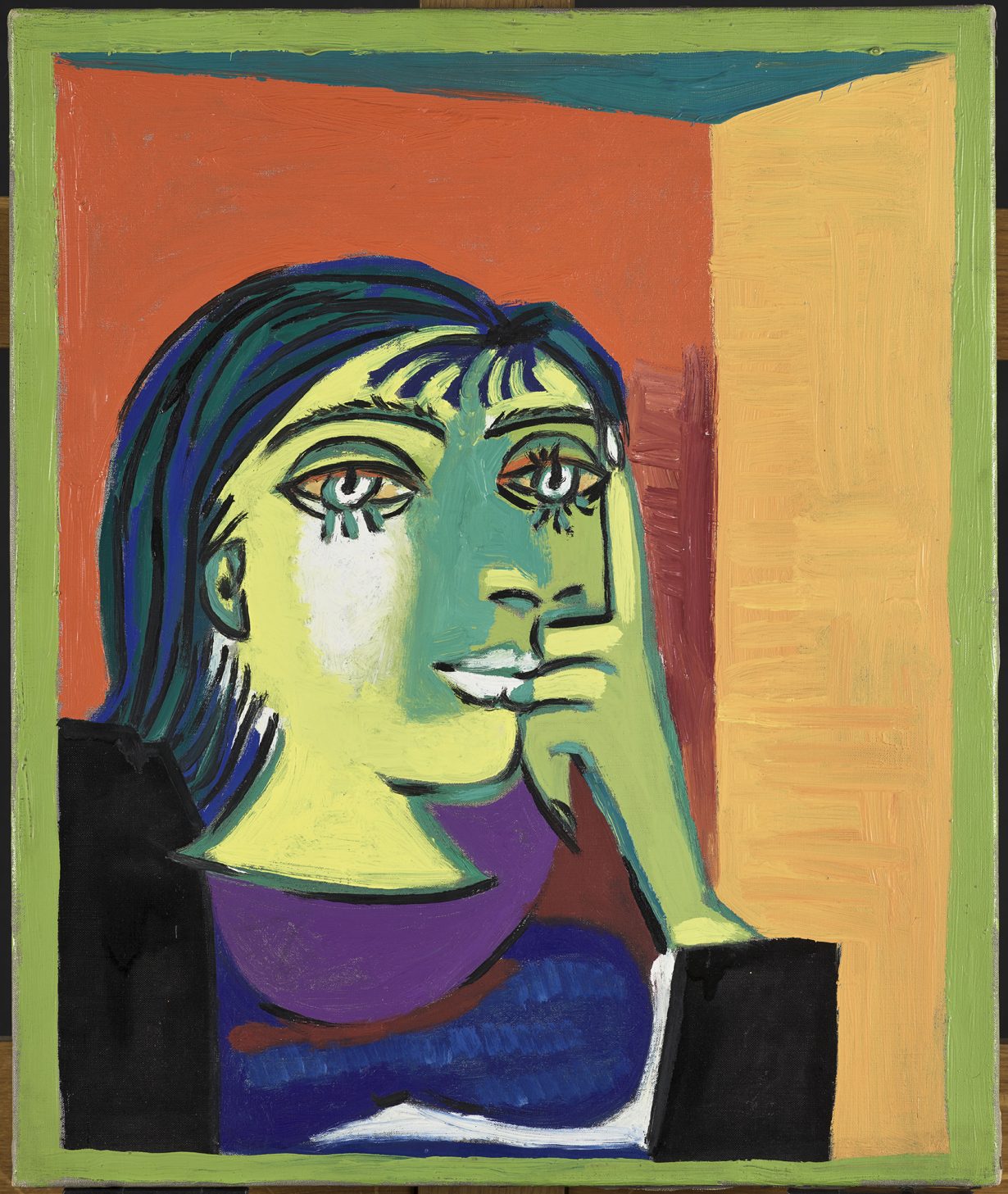

Still, museums continue to prop him up, and Picasso for Asia is a case in point. Although the catalogue tackles the issue of reenforcing his dominating legacy, which includes his maltreatment of women, the same cannot be said for the show itself. And while Nalini Malani’s video Ballad of a Woman (2023), which recounts a story of femicide, is pointedly watched over by portraits of Picasso’s lovers – including the iconic artist Dora Maar, whom Picasso shamelessly reduced to a crying woman (Portrait of Dora Maar, 1937), and the barely legal Marie-Thérèse Walter, whom Picasso courted aged forty-five (Seated Woman with Arms Crossed, 1937) – a wall text tepidly describes him as being ‘at times abusive’ with his ‘muses’. (That latter word ought never be bandied about uncritically in 2025.)

Gender politics aside, questions about how Picasso for Asia equates one Western man with 30 Asian artists go unanswered, though an introductory room tries to set an open stage. Blown up on one wall is Picasso and the loaves, Robert Doisneau’s 1952 black-and-white photograph of Picasso seated at a restaurant table with bread rolls for hands; on another hangs Yan Pei-Ming’s red diptych Young Picasso and His Sister – Permanent Rose (2024). A wall text states that the exhibition looks ‘at the imaginary and unintended conversations between Picasso and artists from Asia’, while a video projection leads with the graphic ‘How do artists____to each other?’ before words like ‘relate’ and ‘talk’ take turns filling the blank.

The sections that follow are organised according to unnervingly whimsical archetypes that Picasso purportedly represents: The Genius, The Outsider, The Magician and The Apprentice. In each, works intermingle like a chain of associations. Among them, Picasso’s 1931 oil on canvas The Sculptor, of an artist gazing at a female bust, is shown alongside his 1906 bronze Head of a Woman (Fernande) and a 1937 plaster cast of the artist’s hand next to its 1936 sugar-lift aquatint imprint on copper plate. All of which sets up Yagi Kazuo’s Space of Applause (1974), a blackware visualisation of hands applauding.

By now, this method of curating East and West as a conversation through forms has become the norm at M+. But Picasso for Asia may have highlighted some pitfalls of the approach. Take Noguchi’s hot-dipped galvanised steel mountainscapes, produced in his final years, which are dotted around one room to frame lifesize bronzes by Picasso from the 1950s, including The Bathers (1956): a trio of minimalist forms based on a man with clasped hands, a child and a woman with outstretched arms. Given the comparable appearance of editions from that series in another M+ show happening simultaneously, expanding on the concept of shanshui, Noguchi unfortunately feels instrumentalised – a shorthand to amplify the cross-temporal connections between Picasso’s figures and Haegue Yang’s three Totem Robots (2010) in the same room, consisting of everyday materials such as clothing racks, electric cables and toys.

Noguchi appears less like filler in another section. Centred on one side of a split gallery is Strange Bird (1945/71), a brushed bronze cast of an upright, three-legged form composed of interlocking parts that highlights Noguchi’s unique sculptural style. Centred on the other side is Picasso’s Figure: Project for a Monument to Guillaume Apollinaire (1928/62), consisting of intersecting circles and squares rendered with welded steel rods, and Jes Fan’s Contrapposto (2023), an irregular, human-size, towerlike frame from which a 3D print of the artist’s thigh muscle, alongside other pigmented resin slabs and glass orbs, hangs like flesh. Oil paintings converse as equally as they can nearby, given the show’s framing, with Picasso’s The Acrobat (1930), a white body on taupe ground contorted into an arch, and Figures by the Sea (1931), a fleshy couple broken into peach shapes and making out, illuminating Feng Guodong’s Body (1978), a biomorphic black mass covering a green sky and desert horizon, and Tang Dixin’s coral and blue-scale plume of entangled arms and legs, Hands and Legs (2015–17).

But even moments like this can’t ease the unease. Take the final section, The Apprentice, with paintings like The Luncheon on the Grass after Manet (1961), where Picasso reworked Édouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863). Not much is said about the term ‘apprentice’, given the tradition for modern Western artists to borrow from Africa and Asia without truly honouring those references, nor how this title positions contemporary artists within a hierarchical framework that puts Picasso up top. Simon Fujiwara’s technicolour painting Who vs Who vs Who? (A Picture of a Massacre) (2024) – a pastiche of The Third of May 1808, Goya’s 1814 painting of Napoleon’s soldiers executing Spanish civilians – shows a ragtag human crowd using a picture of Picasso’s painting Guernica (1937) like a shield against cartoon animals on the attack. Presented next to Picasso’s own response to Goya’s painting, Massacre in Korea (1951), which railed against America’s role in the Korean War, Fujiwara’s version comes off as a pointless joke.

From here, the exhibition’s final work feels like an escape hatch: Yasumasa Morimura’s gelatin silver print A Requiem: Theater of Creativity / Self Portrait as Pablo Picasso (2010) shows Morimura in Picasso drag restaging Doisneau’s 1952 photo, which also serves to plug another show at M+ – Yasumasa Morimura and Cindy Sherman: Masquerades, presenting early works by each of the artists in which both dress up as pop culture figures, from Audrey Hepburn as Holly Golightly to Man Ray as Rrose Sélavy. Here, two artistic icons stand shoulder to shoulder in a thrilling encounter. It works because no one artist is privileged over another, in contrast to Picasso for Asia, which tries to have its cake – present a blockbuster Picasso exhibition while dodging obvious criticisms – and eat it too.

Picasso for Asia – A Conversation at M+, Hong Kong, through 13 July

From the Summer 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.