With her fantastical creatures and humanoid figures, the Zimbabwean painter makes ominousness appear sensual, even seductive

Portia Zvavahera’s first solo museum exhibition in the US bristles with barely subdued tensions. All seven paintings depict wary human and menacing animal figures in uneasy relation to each other, as well as to the grounds that envelop them. Both the figures and the grounds contain passages of thick, tossed-off brush-strokes alongside sections in which print-making techniques have been used to create intricate, veillike patterns. The canvases are aerated by abundant unpainted areas, though these are soiled by scuff marks and paint splotches. Nothing in the pictures appears pure; everything bleeds into everything else.

Like the exhibition title, whose use of both the English and Shona languages nod to the artist’s Western artistic training and Zimbabwean cultural influences, these pictorial tensions don’t resolve so much as coexist in the same space. There’s a kind of double consciousness at play, though the psychological push-pull pertains less to racial identity than species identity. The humanoid figures are crudely rendered, as if their bodies were chalk outlines, and their few detailed elements make them appear more-than-human, as in the meshed, winglike appendages of the three figures who resemble dark angels hovering over a pack of rats (Tinosvetuka Rusvingo, 2024). The animal figures, in contrast, have solid bodies whose colours and textures leech into the surrounding environment, as with the snake whose squiggly yellow skin extends into the soil as lines of runny paint (Hondo yaka-tarisana naambuya, 2025).

Most of what has been written in English about Zvavahera’s work dwells on how she populates her paintings with imagery taken from her dreams. The work’s prevailing mood, though, is of a hushed nightmare, in which portents abound even when nothing horrific has occurred. Above the runny yellow snake of Hondo yakatarisana naambuya, for example, stand three humanoid figures whose bodies are merged together into a giant hunk of raw white canvas that sits like a lake inside the tree-pocked landscape. The landscape has a dark, autumnal colour palette, which together with the coiled snake suggests an impending downfall. These biblical undertones support the other common reading of Zvavahera’s work: that it embodies a syncretic mix of historical African Indigenous religions and the artist’s Christian Pentecostalism.

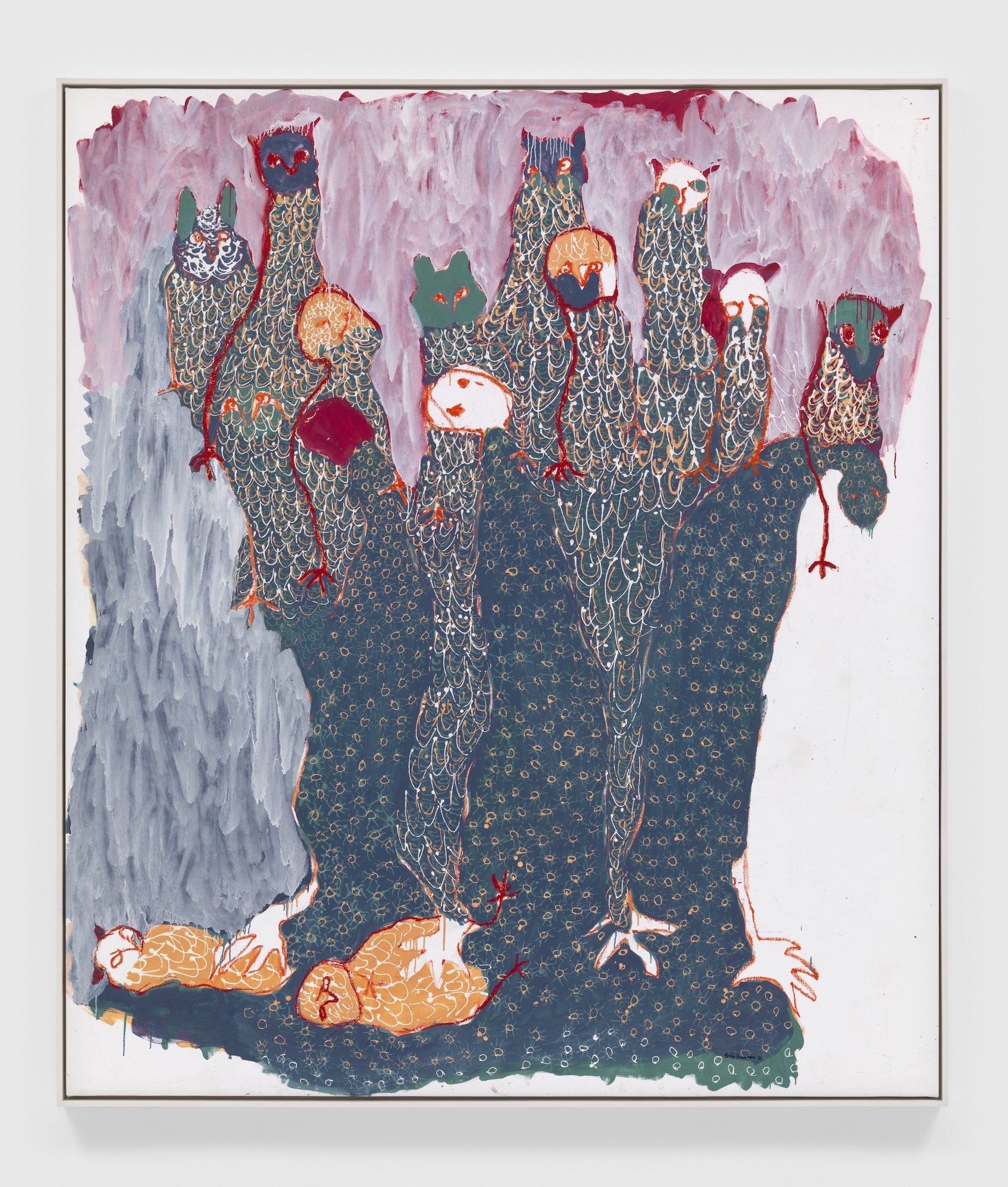

Yet iconographic readings of Zvavahera’s work feel heavy-handed, dutiful. When you’re standing in front of the paintings, their larger- than-human size looming over you, you don’t need an interpretive master key to recognise their gravity. Everything’s happening right there, on the taut canvas, all the drama of colour and shape and empty space, all the brushstrokes layered atop one another as if their accumulation could protect against danger. The paintings make ominousness appear sensual, even seductive; the fantastic hydraheaded owl creature in Ndirikukuona (I can see you) (2021) reminds me of how William Blake and others consider Satan to be the unlikely, glamorous hero of Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667). Perhaps the most fascinating tension in Zvavahera’s work is that it’s at its best when it’s a little bad, when the brushstrokes get sloppy and the humanimals haunting it stop pretending they can remain pure.

Portia Zvavahera: Hidden Battles / Hondo dzakavanzika at Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, through 19 January 2026.

Read next Aichi Triennale 2025 Review: Art’s Losses and Lies