Curated by Hilton Als, this exhibition casts a wide net for the author’s Creole world

Ella Gwendoline Rees Williams, born in Dominica in 1890, only became Jean Rhys during the 1920s, under the influence of her sometime lover and literary Svengali, Ford Madox Ford. She had already, by then, lived a busy life: rebelling against her mother; being packed off to England; becoming a chorus girl; marrying the first of her three husbands; giving birth twice, once to a short-lived son, the second time to a daughter who survived her. She also started to write fiction. It would be four decades until she published her most successful book, Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), a prequel to Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre set in Jamaica, telling the story of Mr Rochester’s first wife. Wide Sargasso Sea brought Rhys fame at last, and is now regularly cited as one of the best novels of the twentieth century.

There is a wide-ranging quality to critic and curator Hilton Als’s Postures (the title echoes that of Rhys’s first published novel, although the title she preferred is Quartet), which is intended as a ‘collective portrait’ of the author and her Creole world. This is very much the world of Wide Sargasso Sea. Race, empire, gender: such themes as are found in her life and work are here given a number of visual counterparts, in no one particular style or medium. Postures may not exactly work as a portrayal; the effect is more that of a giant scrapbook.

The first of four rooms sets out the exhibition’s essential themes through works such as Kara Walker’s hellish West Indies (2014), in which a top-hatted figure oversees his labourers amid the palm trees, or Charlotte (2019), Celia Paul’s intense imitation of George Richmond’s 1850 portrait of the author of Jane Eyre, and Victor Man’s Girl with Goya’s Skull (Memorable Equinox) (2021), in which a pallid nude reclines in the gloom, dropping from a footstool onto the floor, a death’s head lying against her own.

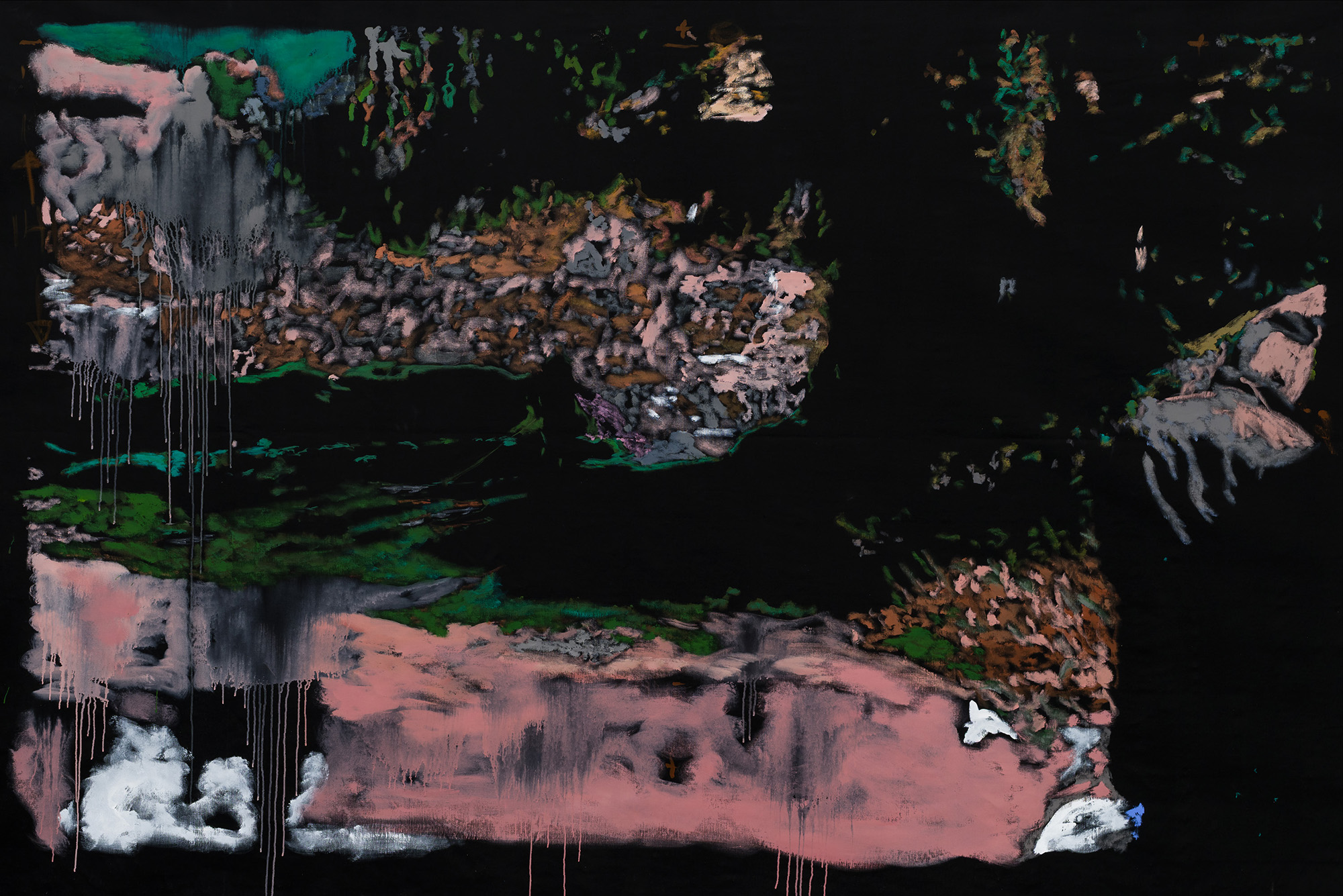

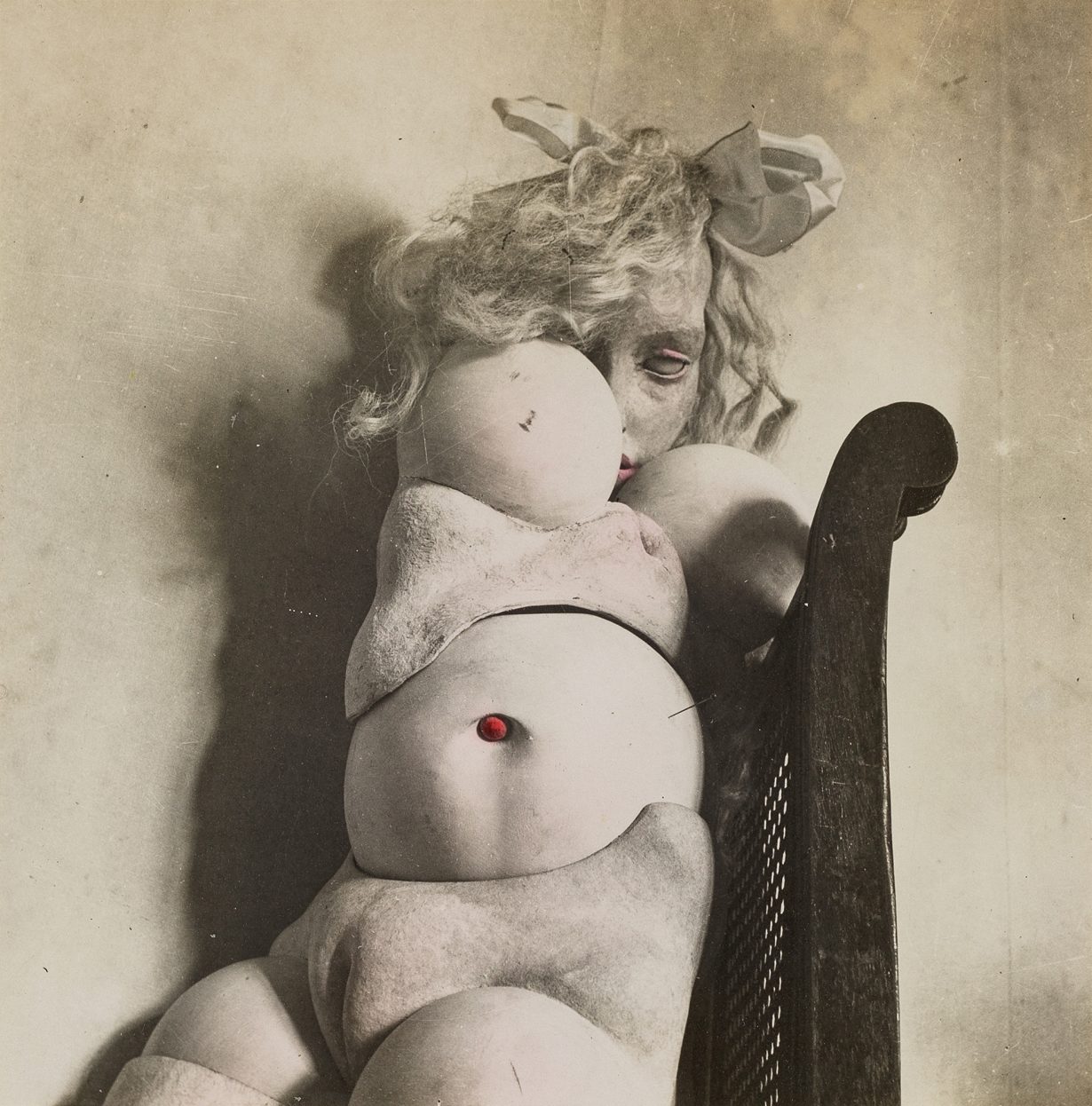

In the next room, Rhys’s Dominica gives way to a European demimonde. On one wall alone we find Eugène Atget’s monochrome photograph of three middle-aged prostitutes standing in a doorway; Cynthia Lahti’s diminutive Green Bust (2022) of almost a century later; Winold Reiss’s bold portrait of a dancer, Katherine (Kathryn) Hamill (1930); Brassaï’s Tonerre sur Paris (1938, printed c. 1960) and an untitled photograph of one of Hans Bellmer’s contorted, disquieting dolls (untitled, 1949). Social realism to Surrealism in five uneasy steps. Als’s selection here takes inspiration from the time Rhys spent in Paris and the early novels in which, he writes, she created a ‘new kind of heroine’, presumably meaning the anguished and isolated women protagonists of novels such as After Leaving Mr Mackenzie (1931) and Good Morning, Midnight (1939). The room’s dramatic shift from figurative work to abstract pieces, such as Walter Price’s Red Line (2025) and Double encounter (2020), is left, bemusingly, to speak for itself.

Most straightforward is the penultimate room, dominated as it is by a slideshow of 69 images in which an unknown photographer captured scenes from Dominican life in the first two decades of the twentieth century. Finally, Postures comes full circle with a space in which the centrepiece is a cotton housedress of Rhys’s, with a red and white floral print – although it is surrounded by more of that curious eclecticism, extending to Leon Kossoff’s Seated Nude No. 1 (1963), a volcanic landscape of oils, as well as Kara Walker’s untitled sequence of eight watercolours (2015–16).

Inevitably, as the portrait of a writer, Postures is incomplete, and the rationale behind its choices are not always readily apparent. There is something to its claim, nonetheless, to ‘explore the interior and exterior worlds Rhys evoked with her pen’, most obviously in its own evocations of the colonial Caribbean and the great novel it inspired.

Postures: Jean Rhys in the Modern World at Michael Werner Gallery, London, through 22 November

From the November 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.

Read next: Bookish Theorics – the artist Anthea Hamilton’s Shakespeare Redux