With London’s art fairs drawing to a close, it’s a good chance to see the shows (you know, the ones in actual galleries) that opened this week. ArtReview‘s editors, the majority of whom could do with putting their feet up by now, select the exhibitions that turned them on most during various stomps across the city.

McDermott & McGough at Studio Voltaire

In 1992 Allen R. Schindler Jr, a petty officer in the US Navy was kicked to death by two of his colleagues in a public toilet in Sasebo, Nagasaki. The same year Marsha P. Johnson was found dead in the Hudson River, New York, a wound to her back. In 2016 Xulhaz Mannan was killed in his Dhaka apartment by Islamic extremists. In a project that sees the southwest London gallery transformed into a chapel of remembrance, these victims of homophobia are commemorated through a series of pen drawings. Oscar Wilde, who was imprisoned for gross indecency in 1895, acts as a patron saint to the trauma of anti-LGBT violence. And yet, sumptuously decorated and candle lit, with an open invitation to LGBT individuals to use the space over the next six months to marry, renew vows or stage memorials and naming ceremonies, it is a project more focused on hope, love and comradeship than misery. Oliver Basciano

The New Museum x The Vinyl Factory at The Store

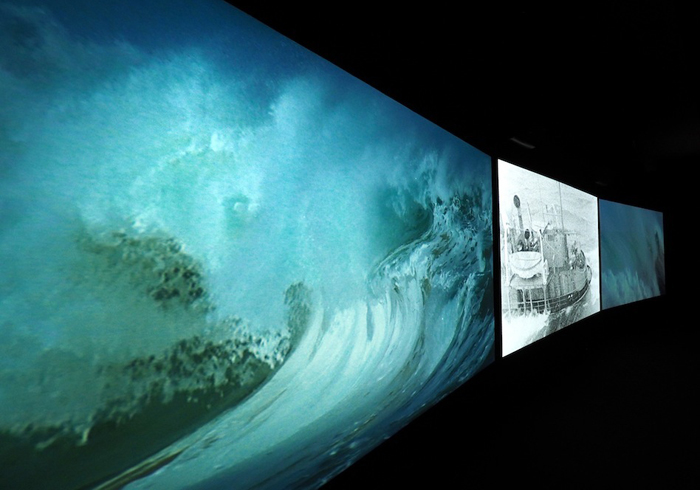

Strange Days is a hypnotic journey through immersive videoworks by 21 international artists (all of whom have shown at New York’s New Museum in the past decade), displayed in a maze-like structure across the three floors of this brutalist landmark. The number of issues and narratives threaded through these works is dizzying (and their quality not always consistent) but collectively they function as ruminations on the human and posthuman conditions – from Camille Henrot’s neurotic story of the universe, through Daria Martin’s sensual fantasy between human and robot, to Wong Ping’s fucked-up domestic tale rendered in technicolour animation. It’s worth the visit for John Akomfrah’s Vertigo Sea alone, an epic three-channel installation delving into the violent histories underlying the surface of the ocean – from colonisation to slavery, whaling and the migrant crisis – via archival footage and sublime, mesmerising shots of the sea. Louise Darblay

Francis Upritchard at the Curve

It’s nice, sometimes, to be perplexed. Francis Upritchard’s recent sculptures tangle fashion, craft and archaeology: there are multicoloured polymer humanoids, spindly and delicately featured, skin painted in hues of blue or desaturated anaemic tones, etched with rune-like symbols and standing on lilac pedestals like high-fashion druids. There’s a table of small gnarled bronze body parts, a vitrine of jewellery-adorned ears made from colourful leather, shelves displaying an assortment of felted hats, and ceramic and glassware artefacts. Finally, there are pseudo-Greek sculptures and reliefs of centaurs with melted faces and mangled bodies made predominantly from Balata, a wild rubber extracted (with the help of a local producer) from trees in Brazil’s Monte Alegre. You could say that Wetwang Slack (named after an Iron Age burial site in Northeast Yorkshire) references the ways in which history and culture can be invented and, in some instances, reinvented to suit particular regimes or belief systems. Or you could see it as a fantastical civilisation, a world that has evolved from myths made real. Either way, bring your imagination. Fi Churchman

Eliseo Mattiacci at Richard Saltoun

Richard Saltoun’s largely conceptual programme tends to focus on photography – recent exhibitions in his new space on Dover Street, where he moved in February, have included the group shows Women Look at Women and AKTION: Conceptual Art and Photography, the latter containing work by 26 artists from 13 countries during the 1960s and 70s; Victor Burgin: Voyage to Italy, a 2006 suite of photographs plus a videowork executed on the site of the Basilica in Pompeii, occupied the space throughout September. For its latest exhibition, the gallery stays in Italy but replaces the photography with an installation of 58 aluminium volutes conceived by Eliseo Mattiacci in 1980–81. Each a roughly human-height sculpture consisting of two spirals formed from and connected by a single, continuous staff, they crowd the gallery, hooked over a partition, hanging from walls and resting on the floor, their moulded shapes and surfaces bringing to mind fiddlehead ferns, a shepherd’s staff, a treble clef and the column capitals that were their inspiration: Mattiacci has described their omnipresence in Rome as a sort of objet trouvé. This is the first UK solo exhibition by the artist, now in his late seventies and a major figure of Italian sculpture – perhaps all the more so for resisting categorisation. David Terrien

Lawrence Abu Hamdan at Chisenhale Gallery

In a blacked-out and soundproofed booth at the Chisenhale Gallery two speakers broadcast stories from Saydnaya prison. Survivors of the Syrian torture centre, where an estimated 13,000 political prisoners have been executed since the outbreak of war, describe a regime of silence broken by the sound of brutal beatings being administered elsewhere in the building. The floor around this cell is cluttered with radio theatre props – a car door, a ladder, a catalogue of locks – used by Lawrence Abu Hamdan to mimic the sounds (slams, cracks, creaks) the prisoners remember from their otherwise silent incarceration, which helps to corroborate their testimony and serve the human rights advocacy that underpins the artist’s practice. Yet for all its diligent research the work succeeds as art because it takes advantage of the affective possibilities of sound and space that are denied to bare legal testimony: sitting through the silence that descends on listeners after the sound installation concludes – to disturb which in Saydnaya might give the guard a reason to beat you to death – is to appreciate Hamdan’s ability to translate forensic evidence into a representation of suffering which acts on the body through the senses. The exhibition is complemented by the video installation Walled Unwalled (2018) at Tate Modern, which further extends the artist’s investigation into the means by which state-sanctioned violence transgresses and redraws the structures – architectural, political and sensory – that shape our experience of the world. Ben Eastham

Anna Hulačová at Kunstraum

Anna Hulačová’s strange objects are leaky with the surreal. A four-legged table and an oversized skateboard are inlaid with glossy marquetry, crawling with anemones and amoebas. On top, concrete sculptures of writhing tentacles, one side cleaved flat like a node of quartz, a polished surface onto which the overlapped faces of two women are drawn in monochrome, holding a daisy collectively between their lips. The Czech artist’s sculptures are full of these jumps, from real to imaginary, from thing to image, from solidity to sensuality; as if carving and cutting dead matter might reveal a secret inner life – inert stuff made paradoxically organic and alive. J.J. Charlesworth

Online exclusive published on 5 October 2018