A new book on urban sprawl drops just in time for those fleeing city centres

The city has apparently ‘lost its appeal’ during lockdown. No space; too many people. Those who can afford it are looking to get out, many of them to that place of supposed refuge – the suburb. For those wondering precisely where to move, Jason Diamond’s The Sprawl, a conversational, at times personal, cultural history of the US suburbs, promises to be of help. Consider it a Sightseeing Tour of American Suburbia and its Famous Homes: highlights include the modernist Ben Rose House in Highland Park, Illinois, famous for its appearance in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986); the quaint town of Seaside, Florida, that provided the basis for the domed TV set of The Truman Show (1998); Bay City, Michigan, the quiet, neglected hometown of Madonna Louise Ciccone; or an unremarkable house in Lodi, New Jersey, where Misfits’ singer Glenn Danzig grew up. But beyond the famous, over half of the nation’s population already lives in what qualify as suburbs and so, as the author asserts, we are ‘still very much in the middle of the suburban century’.

This is not just about pandemic property speculation. The wider questions of where culture comes from and what stories we pay attention to are among the most important of our time: looking beyond the noise and jostling of the city is a necessary part of that. While other recent publications – such as Amanda Kolson Hurley’s Radical Suburbs (2019) and Marcia Chatelain’s Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America (2020) – have cast new light on the set view of the suburbs as trapped, stale and pale, The Sprawl, itself a sprawling overview, seems happy to affirm the stereotype of suburbia as a place of anxiety, boredom and alienation.

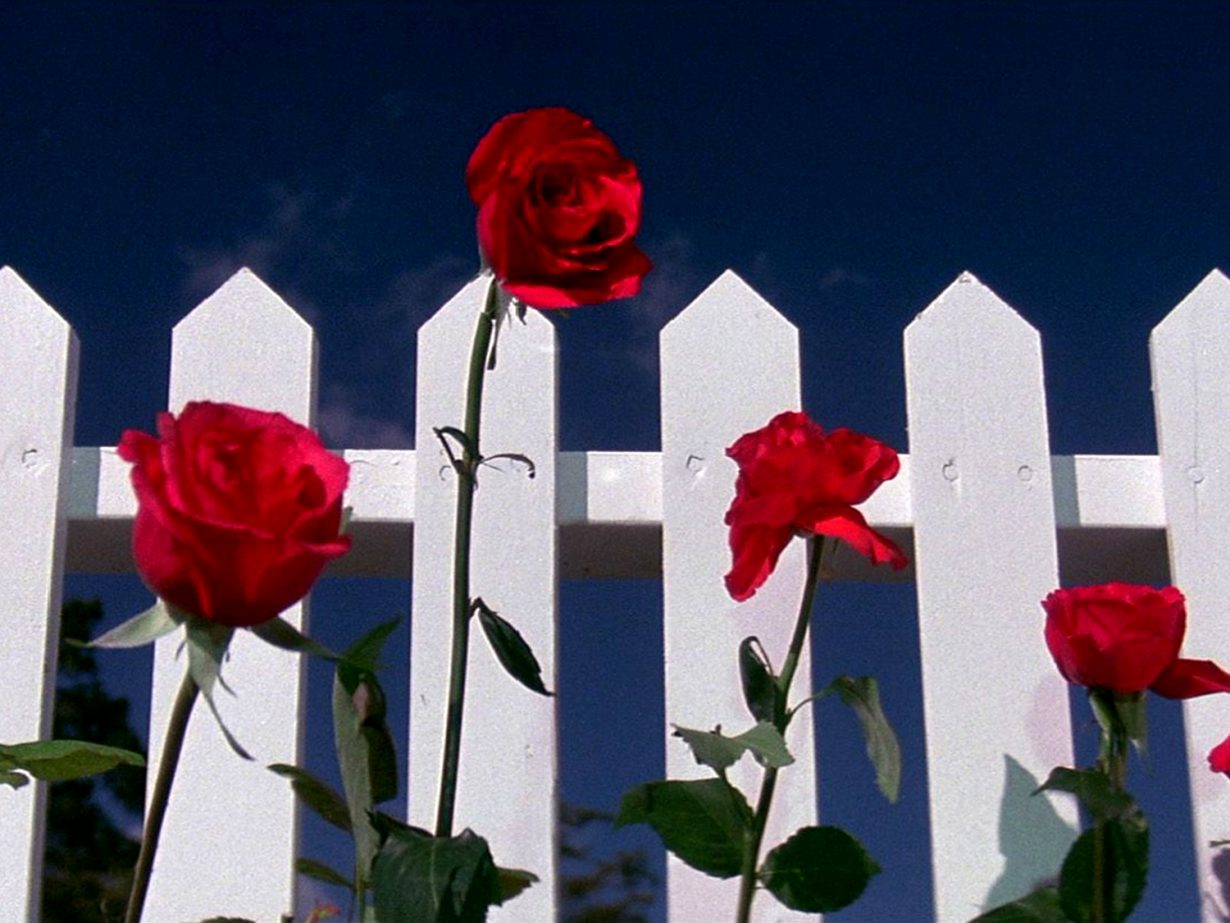

Setting itself primarily among the enclaves of the ‘Chicagoland’ area in which the author, now a journalist, grew up, the book is useful as a primer on some of the policies and politics that shaped the American ’burbs. Diamond charts the origins of several suburbs, among them Zion and McHenry in Illinois, that all share the same fate: pastoral utopias designed to be an escape from the industrial grit of the city that soon became trapped within their own picket fences. William Levitt, one property developer he explores in detail, set up a series of planned towns across the US from the 1940s onwards, all of which had active policies to ensure that buyers would be Caucasians only. Levitt, a Jew who claimed not to be racist, blamed his customers for the policy, describing it as ‘their attitude, not ours’. Diamond is keen to stress the tensions and shifting diversity of the suburbs, but his book never moves far beyond long-established (white) portrayals: the films of John Hughes (a biography of who Diamond has previously written), the stories of John Cheever, the static images of the suburb in Blue Velvet (1986), The Virgin Suicides (1999), Back to the Future (1985). There are interesting asides – like Mr. T getting into a landscaping dispute with his neighbours in the 1980s after felling a few oak trees that he claimed triggered his allergies; or how Leave it to Beaver (1957–63), The Munsters (1964–66), The ’Burbs (1989) and Desperate Housewives (2004–12) were all shot on the same Hollywood set – but their wider cultural and racial implications are never really followed up. While Diamond gestures to the limits of constantly showing the suburbs as a place of homogeneity and stagnation, he doesn’t move beyond them.

Perhaps this book’s most insightful contribution, whether intentional or not, is the way in which it embodies a suburban mindset: Diamond’s first points of reference and main focus are on wellknown films, music, books – pop stuff made in places other than the suburbs. At one point he likens the latter to Anakin Skywalker: full of potential, but also with a dark side. It is only once the author reveals a bit of himself – a practically homeless teenager drifting between separated parents – that this project achieves a greater resonance. His previous posturing – hiding behind a ream of cultural references – is part of the suburban mask that Diamond seems reluctant to investigate. ‘It felt so surreal, like something out of a movie,’ he writes of a ‘McMansion’ his father has settled into. ‘But so did everything else, really,’ he shrugs, not examining any further that peculiar aspect of the snake eating its own tail.

But that’s part of the rub: the suburb is, at this point, primarily a cultural commodity, regurgitated and re-ingested in the US and exported internationally over generations. While any examination of the suburbs has potential as a reflection on fringe conditions, on power and agency, reinforcing these familiar representations of the suburb only reinforces its role as a normative, Spielbergian vector that has infected large parts of the globe. ‘The future is still in suburbia. We just need to reclaim it,’ The Sprawl blandly concludes. Why not start by trying to find those stories and songs, dreamed up in some quiet, poster-lined basement, we haven’t already heard?