Her latest work examines how displaced cultures might envision brighter futures

Born to a Bosnian mother and Yemeni father who emigrated to the US, Alia Ali draws on a question that often concerns diasporic communities: how to identify with your heritage when physically separated from the nation, or nations, in which it was born. But in the case of Yemen it is a question that is perhaps more urgent than it might otherwise be. “Where is the place for Yemen when the land is being erased?” Ali asks during a Skype conversation between the two of us last summer. In 2019 the UN described Yemen as the site of the world’s worst manmade humanitarian crisis. An ongoing civil war, US-backed Saudi bombing campaigns, food and medicine blockades, cholera and widespread famine have, in concert, brought a suffering population ever closer to death. But such atrocities too rarely transcend such reports to register in our collective imagination. When they do and we are confronted by the sheer enormity of the situation, it can be difficult to imagine – as Ali prompts us to do – a different future for Yemen. But it is precisely this that is the focus of her latest work, titled The Red Star (2020).

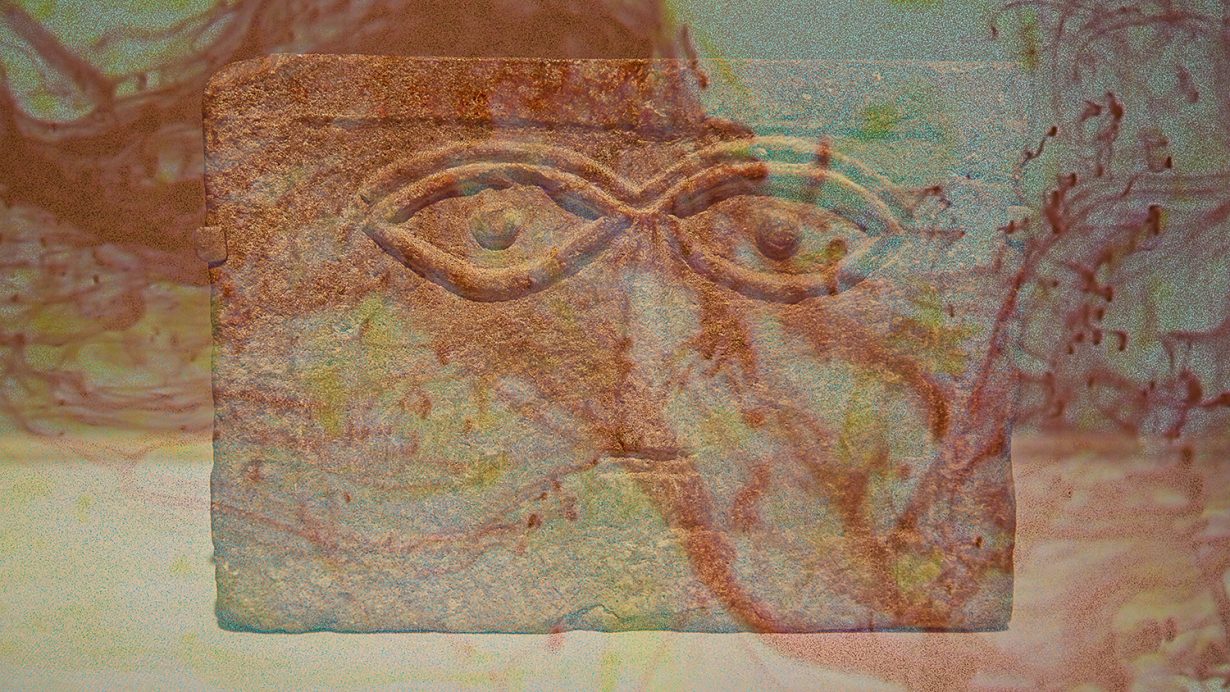

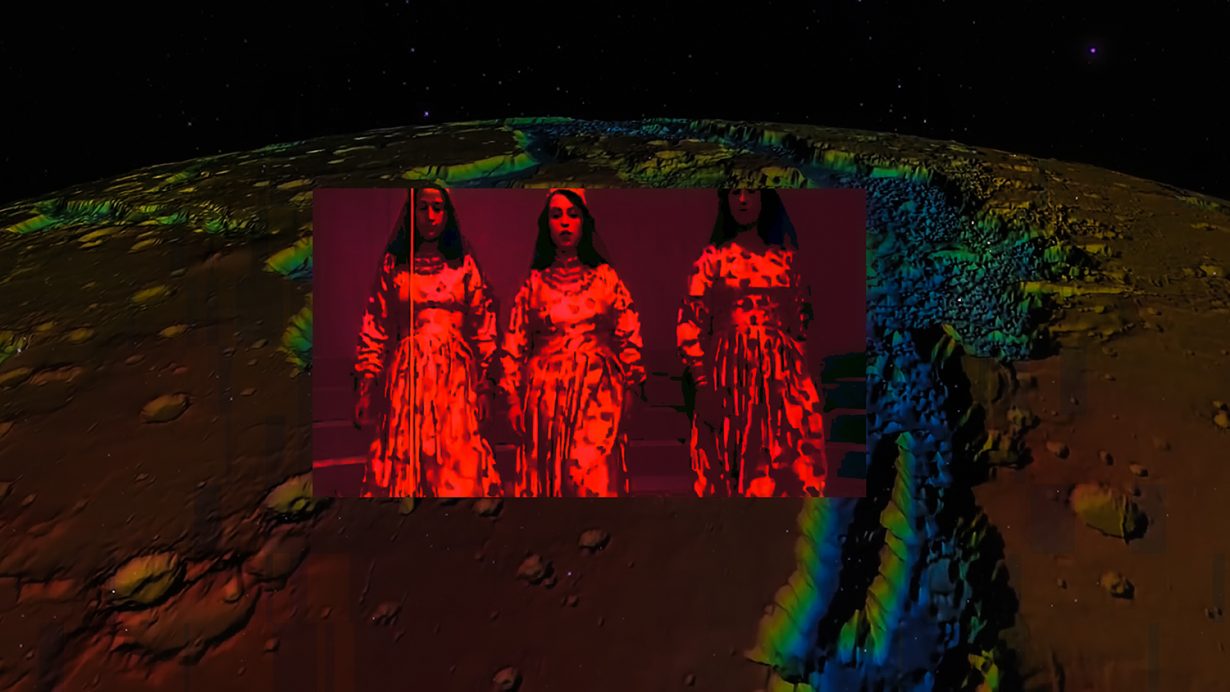

The 13-minute video installation is a psychedelic, multimedia vision of Yemen that pulls together contemporary imagery recognisable to Yemenis – footage of traditional Yemeni dancing, the back-streets of Sana’a’s Old Town, the lively sounds of strumming oud music – while also drawing on references from further back in time and space, to weave archive footage, mythology and storytelling in order to address the question of the country’s future. Against a jarringly fluorescent digital backdrop, we see a live spider moving across a web while a voice – Ali’s – recounts (in English and Arabic) the legend of Queen Bilqis.

In contrast to the biblical version of the legend, in which Queen Bilqis of Sheba travels across Arabia to lavish King Solomon of Israel with splendid gifts, in the Yemeni telling, Solomon crosses the continent and is granted an audience with the queen on the condition that he bring her a gift of equal size to her power. His gift is the Red Star.

Back in the installation, the collected sounds from a 1997 expedition to Mars accompany a CNN news report of three Yemenis who that year sued NASA for their incursion of the planet – the Red Star – that they say their country has owned for 3,000 years. Towards the end, we hear the voice of a Yemeni refugee who recounts his last sight of Yemen as he left on a boat that delivered him from the current civil war to the United States.

Ali’s Bosnian relatives were forced to flee during the Bosnian genocide of 1995, and while some of her Yemeni family, with whom she most closely identifies, remain in Yemen, those who left before the start of the war in 2014 have been unable to return. “What is it that makes a Yemeni?” Ali asks during another of our interviews. From the summer into the autumn, against the backdrop of the worsening pandemic and spiralling of American politics, Ali and I speak several times over Skype – Ali from her home in Los Angeles; me from London – as we discuss her art and the role fantasy might have in imagining a different world.

The urgent issue diasporic Yemenis face is that much of their homeland is being destroyed. In the face of that, Ali says, they must look beyond the physical to other aspects of their shared heritage in order to construct a Yemeni identity. “Talking to Yemenis in the diaspora, I realised the story of the Red Star that we’re told as children is something we all share. I thought this was profound: the idea that there could be something cosmic that pulls us together.”

If the attempted colonial erasure of Africa’s past gave rise to Afrofuturism, Ali’s The Red Star might be thought of as a kind of Yemeni-futurism: present reality is dominated by an oppressive force; any thoughts of a future must be reimagined shorn of these. It’s a kind of futurism that would distinguish itself from the lens of Arab Futurism, which, Ali says, flattens the particularities of life in cultures and communities across Arabia. “In Afrofuturism, Sun Ra started thinking about another planet. To him there was no more room or potential for future generations of the African diaspora to imagine themselves because of the baggage of colonialism and imperialism. Because of the trauma, you’re sort of paralysed. You ask yourself: where else do you see yourself?”

“Happy Arabia. It’s known for being the land of plentiful; in architecture, jewellery, textiles, salt, coffee, honey, frankincense, myrrh,” the narrator, Ali, says in the video as a spider dangles from a web. The arachnid, Ali says, is the incarnation of one of the Quran’s most quietly influential figures, who once saved the Prophet from a mob by weaving a web across the door of the cave in which he sought refuge. No one could have entered the cave and left the cobweb intact, his pursuers surmised. It is through Ali-the-spider that we learn the disastrous consequences of Queen Bilqis’s acceptance of King Solomon’s gift; the gift of the Red Star led to the march of organised religions across the Arabian Peninsula and thus, Yemenis believe, precipitated the subjugation of Yemen’s people by foreign invaders.

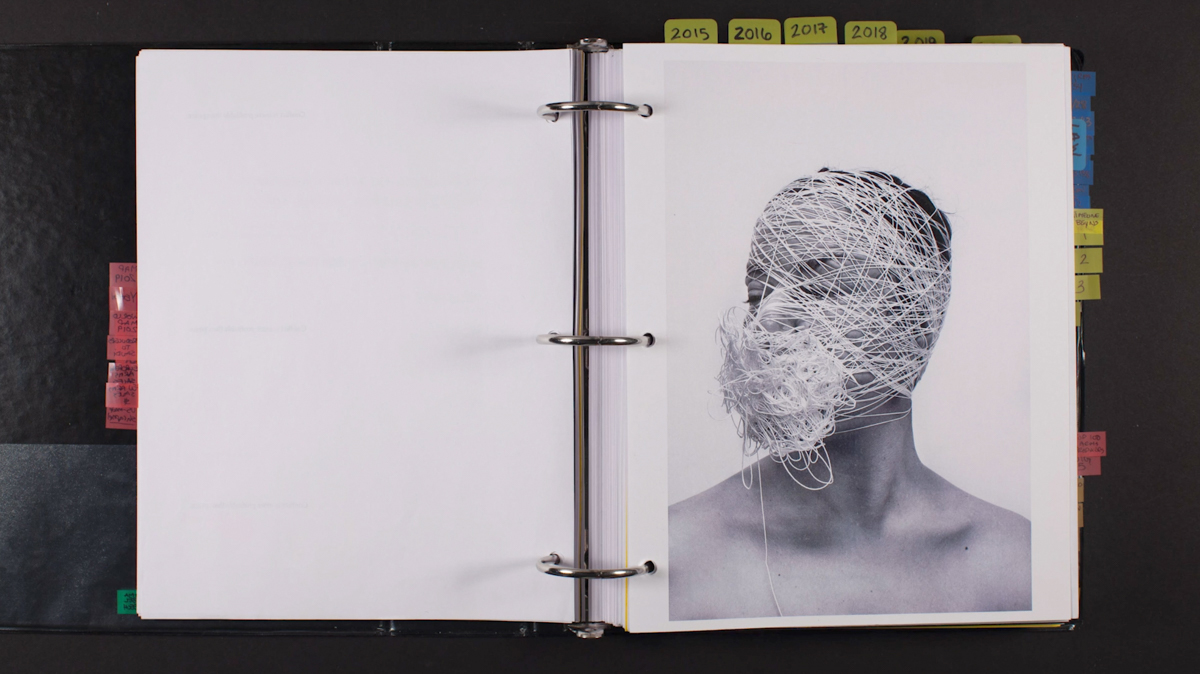

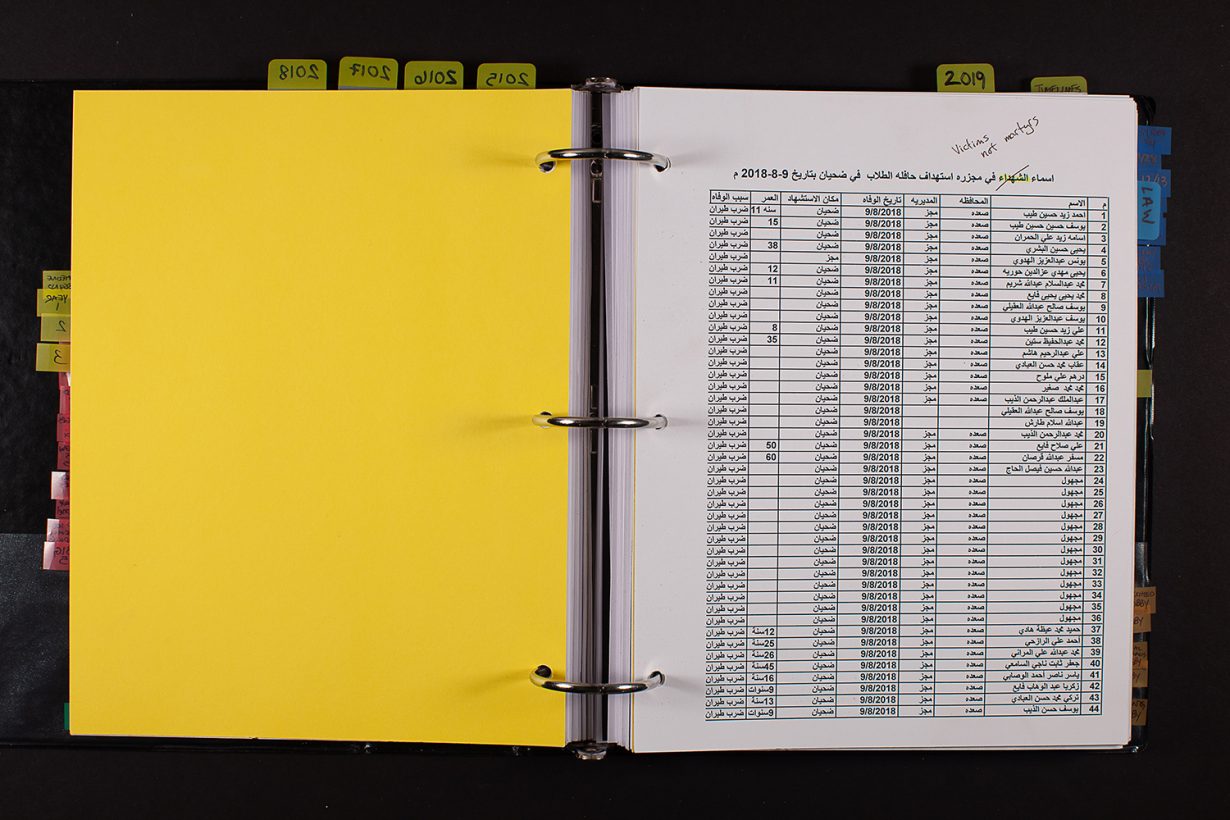

No assessment of modern Yemen would be complete without acknowledging the involvement of the United States and Saudi Arabia in its plight. Subtly, Ali makes their consistent, oppressive presence known: through snippets of the American national anthem; through photos of Yemeni artefacts on display in American museums; through fireworks exploding over footage of Sana’a’s Old City. In one of Ali’s earlier video installations, from 2018, the artist is filmed standing on Capitol Hill reading out the names of Yemenis whose lives have been lost during the war; it was made to coincide with a US Senate vote on whether or not to stop the supply of arms to Saudi Arabia. The 17-minute video, spliced with photos, starts with the Saudi-led airstrike that killed at least 26 children onboard a bus in Dhahyan earlier that year. “I wanted to name the victims but also the culprits; the weapons-manufacturing companies, the lobbyists,” Ali says. Her latest work is the inverse of this. Rather than an explicit presentation of their crimes, in The Red Star (which also nods to the fact that between 1969 and 1990, the People’s Democratic Republic of South Yemen, as it was then known, was the only socialist state in the Arab world), Yemen’s invaders are merely inferred. There is a kind of defiant self-determinism at play here: by the oblique reference, Ali recognises the hand foreign powers have had in shaping Yemen but chooses not to dwell on it as a part of what it means to be Yemeni, instead giving space to the elements of traditions and histories that present Yemeni culture as dignified and joyful.

This is necessary when language can work as much to obscure as to elucidate. “During the Iraq War, language became propagandised,” Ali says. “I grew up seeing how language can be used as a weapon and how it and other things – the camera, translation – can be used against cultures. If you type madrassa into Google [in Roman letters] you’ll often see it as a training camp for terrorists, but it’s the only word we have for ‘school’.” Like many Muslims and Arabs in post-9/11 America, Ali’s immigrant family felt the newly strengthened hand of Islamophobia; two weeks after the attack, her father was illegally fired from his job. Arabic, the language with which Ali would communicate with her father, ceased to be spoken in their home. To be American, the family was forced to cut its links to its past.

“I wanted to make a work that was above all for Yemenis… Yemenis watching this can think: ‘Oh, we come from something bigger, a place that had projected beautiful things for us, and what we’re living right now is the projection of our colonisers’.” It is an act of aspiration and puts on the table the notion that Yemen, and indeed any community at risk of erasure, could still have a future, one shaped not by outside oppression but the imagination of those who will live it.

Nadia Beard is a journalist and pianist based in Tbilisi