As Istanbul’s cultural establishments continue to battle reputational issues, Kaya Genç advocates for greater accountability amid the country’s growing illiberalism

Last year was supposed to salvage the reputation of the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts (IKSV), one of Turkey’s leading art institutions. And yet, despite an initial bout of optimism and a visionary roadmap resembling some sort of progress, recent events have swiftly brought the institution back to reality.

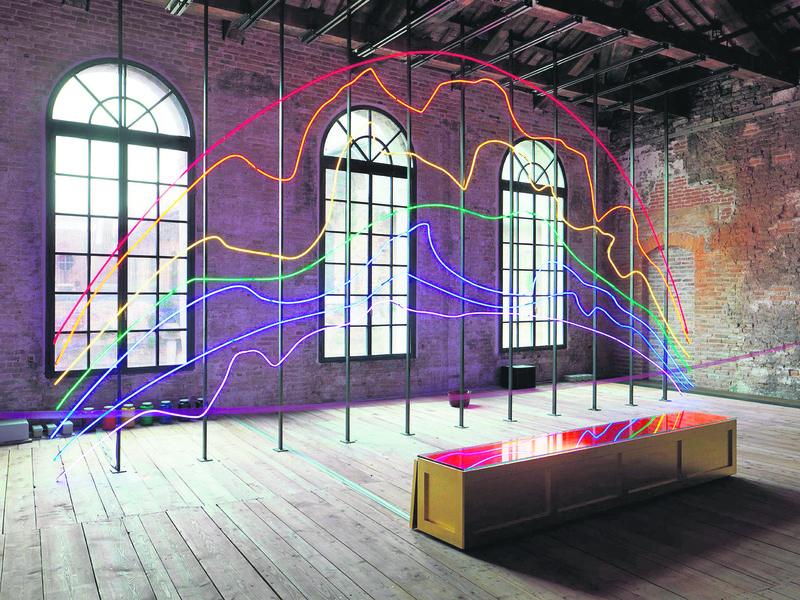

The 2024 edition of the Istanbul Biennial, organised by IKSV since 1987, was postponed until 2025 following the biggest crisis in its history. Defne Ayas, a widely respected Turkish curator who had been selected by an advisory committee in 2023 to organise the event, was replaced by Iwona Blazwick, who is currently an employee of the Saudi government. IKSV, it appeared, deemed Ayas too risky for such a largescale event. (At the 2015 Venice Biennale, the Turkish government intervened in an exhibition Ayas had curated by the Turkish-Armenian artist Sarkis and halted the publication of the exhibition catalogue, which included a reference to ‘the pains of the Armenian Genocide in 1915’; Sarkis and Ayas responded by displaying the catalogues in a coffin inside the pavilion.) Turkey’s art community was incensed and Istanbul-based artists pulled out of Blazwick’s biennial. In the end, IKSV had no option but to cancel the event.

And so, 2025 put the Istanbul Biennial back on the map, internationally and locally. The announcement of the Beirut-based Christine Tohmé as the curator of the cursed 18th edition was met with optimism. Tohmé wasn’t a ‘super-white European’, as some complained after Nicolas Bourriaud was commissioned to curate the 16th event in 2019. This ‘curator-director’, who focused on the Global South’s perspective and who founded Ashkal Alwan (the Lebanese Association for the Plastic Arts) in 1994 to initiate contemporary artistic practice, could inspire Istanbul’s creative communities. Tohmé’s proposal, The Three-Legged Cat, promised a ‘quarterly public programme in close collaboration with local art initiatives’. Exhibitions, publications, performances and discursive gatherings awaited Istanbul in three consecutive ‘legs’ to run over the course of three years.

The promise of progress, as far as I could identify at the time, felt real. At the biennial’s launch in September last year, Tohmé spoke about genocide, ecocide and the patient resilience of locality, to a standing ovation. The opening week’s live performances, including Selma Selman’s Motherboards and Ahmad Ghossein’s So your heart aches, huh?, among others, were encouraging. Tohmé wanted the second floor of Zihni Han – the HQ of a former Istanbul shipping agency newly opened to the public in 2025 as a key biennial venue – to serve as ‘a shared hub for gatherings and events’, inviting the city’s artistic communities to pitch ideas.

However, this dialogic, expanding vision of a collaborative city biennial never really solidified. The initial optimism finally faded when, in December, IKSV announced ‘Tohmé’s decision to step down [from the biennial] due to personal circumstances’. The wording was familiar in its cryptic language: ‘in line with her current decision, the programme will not continue as originally planned, and the 18th Istanbul Biennial will come to a close after its first leg’. The advisory board – comprising Ahu Antmen, Lydia Gatundu Galavu, Gözde İlkin, Renan Laru-an and Sally Tallant – are due to announce the curator for the 19th Istanbul Biennial, scheduled for 2027, this year.

Of course, the period of confusion about what happened and why is not Tohmé’s fault. IKSV’s approach was to keep a stiff upper lip: never apologise, never explain. What happened to the other two legs of Tohmé’s biennial? Speculation inevitably followed: that Tohmé was ill, taking care of her ailing mother, or both. An IKSV spokesperson said the decision was ‘unexpected’ for them as well. “I was genuinely surprised by the news,” a person who worked for the event told me. Another culture worker, from the biennial’s production team, characterised Tohmé’s exit as a “shock wave”. Those who were prepared to work at the 2026 and 2027 events had to alter their plans.

In her initial proposal, Tohmé said her extended three-year time frame would allow the biennial to ‘engage more deeply with the local scene’ and ‘support generations of artists in connecting with their regional and international peers, building alliances, and confronting new realities’. Many might worry that the cancellation will now halt such a possibility. But Istanbul’s artistic communities already know how to conduct dialogues with their peers and confront ‘new realities’. They are well-connected and articulate realists who can see through the corporate speak of IKSV, which, in the wake of Tohmé’s exit, promised to ‘continue to advocate for greater accountability and transparency’ – values that Istanbul’s artistic communities have been desperately, consistently demanding. At the same time, these artists need institutional support: funding for projects, established mechanisms that will help disseminate their finished works to larger audiences locally and internationally. This opportunity of funding and support, offered by the biennial, has vanished this year under opaque circumstances. That the biennial already lost its former ‘Production and Research Programme’ (ÇAP), run by Istanbul-based artist Zeyno Pekünlü from 2018 until it was ‘concluded’ in 2024, will only feel heavier in years to come.

It is increasingly clear that IKSV wishes to appear apolitical while it consistently pussyfoots around issues linked to Turkey’s growing illiberalism. The imprisonment of Osman Kavala in 2017 (charged with ‘conspiracy to overthrow the government’ through his art patronage) traumatised a generation of culture workers. In 2015, IKSV cancelled the screening of the documentary Bakur/North after the Ministry of Culture issued a warning about the film’s political content; 22 films consequently withdrew from the Istanbul Film Festival to protest what was widely viewed as censorship. As much as they require funding to realise their projects, Turkey’s art communities also need an institutional determination to protect their works from the censors. Standing up to censorship requests may demand courage, but it also builds prestige.

Six months before the opening of The Three-Legged Cat, Istanbul’s mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu was imprisoned, charged with ‘corruption, extortion, bribery, money laundering, espionage, and supporting terrorism’; three weeks before Tohmé delivered her opening speech, the mayor of Beyoğlu, the area of the city that is the setting for the biennial, was put behind bars, charged with ‘membership in a criminal organisation’. Not one word of protest from IKSV for its local partners, the Beyoğlu Municipality, who allowed the biennial team the use of the Garden of the Former French Orphanage as the venue for the press briefing. That IKSV is aware of its reputational crisis is apparent from its recent appointment of Yeşim Gürer Oymak to the role of its new general director. For the first time in its history, a woman will lead IKSV.

IKSV, in the past, was a different foundation – reason for us to expect it to do better. The first Istanbul Festival, held in 1973 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Republic of Turkey, primarily featured classical music. Film screenings, theatre, jazz, ballet performances and exhibitions held in historical venues soon became part of the programme. The year 1987 marked the beginning of the International Istanbul Biennial. Other festivals followed: Film and Theatre in 1989, Jazz in 1994 and Design in 2012. IKSV’s former chairman Şakir Eczacıbaşı acknowledged the vitality of local solidarity. A leftist photographer and the cofounder of the Turkish Cinematheque Association, he boldly faced the Turkish military junta in 1980 when it shut down his Cinematheque for political reasons. In the face of the state, he continued to show resilience, demanding the respect of IKSV as a cultural foundation after taking its reins in 1993; he also took steps towards institutionalisation that helped IKSV gain prestige among artistic communities.

Obviously, the current political climate in Turkey has made such speaking up harder. But when numerous independent actors and cultural institutions do so, despite all of the risks involved, the foundation’s silence becomes all the more audible. Case in point: in August last year, just weeks before the biennial’s opening, a new wave of MeToo-style harassment and abuse allegations swept across Turkey. Women and LGBTQ+ people accused prominent men in the arts sector: several art critics, editors, artists and a prominent collector were named and shamed over the course of a few weeks in August. The progressive contemporary arts publication Argonotlar suspended its operations following such allegations made about its founding editor (it was later revived under new leadership); the Turkish branch of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA) announced it had expelled three members. Actions had consequences: complaints about bad practices led to responses and results.

This is how Istanbul’s artistic communities might operate in 2026, boldly and transparently, in a period of convalescence from a decade of authoritarian rule. Sadly, each edition of the Istanbul Biennial seems to bring with it a new layer of opacity. To truly salvage its reputation in 2026, IKSV, under its new leader, needs to embrace this spirit of Istanbul’s independent initiatives and youth groups. It needs to treat accountability and transparency as guiding principles, not just cryptic words in press statements.