The open-world adventure draws visual force from a multitude of influences – Star Wars, Hayao Miyazaki, London’s brutalist masterpieces – to imagine a desert planet that vibrates with deep, geological time

Sable (2021) is an open-world exploration videogame developed by Shedworks, a two-person team that began work on the project in their garden shed in London back in 2014. While over time many others have added their talents to the mix, including indie-pop band Japanese Breakfast who produced the game’s stirring original soundtrack, Sable remains a small, intimate experience, despite the fact it’s set in a vast, trackless desert environment.

The game has many inspirations – the beginning of Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015) where Rey abseils through the skeleton of a hulking, wrecked Star Destroyer on a remote sandy planet, Hayao Miyazaki’s environmentally-conscious anime Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), and the beautiful, vibrant line work of French comics artist Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud, who was himself obsessed with many a psychedelic desert. Add to this a profound love for architecture – temples reminiscent of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis House in LA, the soaring towers of artist Minoru Nomata, the pastel-pink stairs and walkways of Ricardo Bofill’s postmodern apartment complex La Muralla Roja in Calpe, Spain, the ritualistic steps and ornamentation of the Italian architect Carlo Scarpa (also present in the game’s logo), and even the sustainable desert ‘arcology’ of Paolo Soleri’s experimental town Arcosanti in Arizona all appear as major influences.

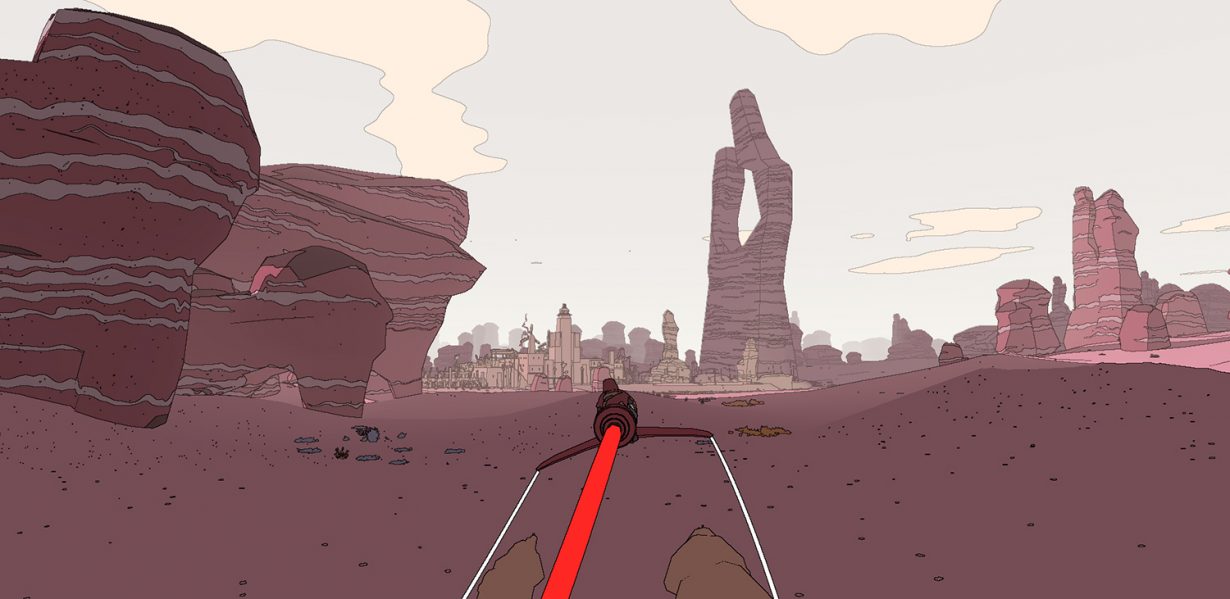

In Sable, you explore several distinctly arid zones, zooming through desert valleys and desiccated forests on your hoverbike, while also clambering up and over mountains and cliffs in order to delve deeper into mysterious ancient ruins.

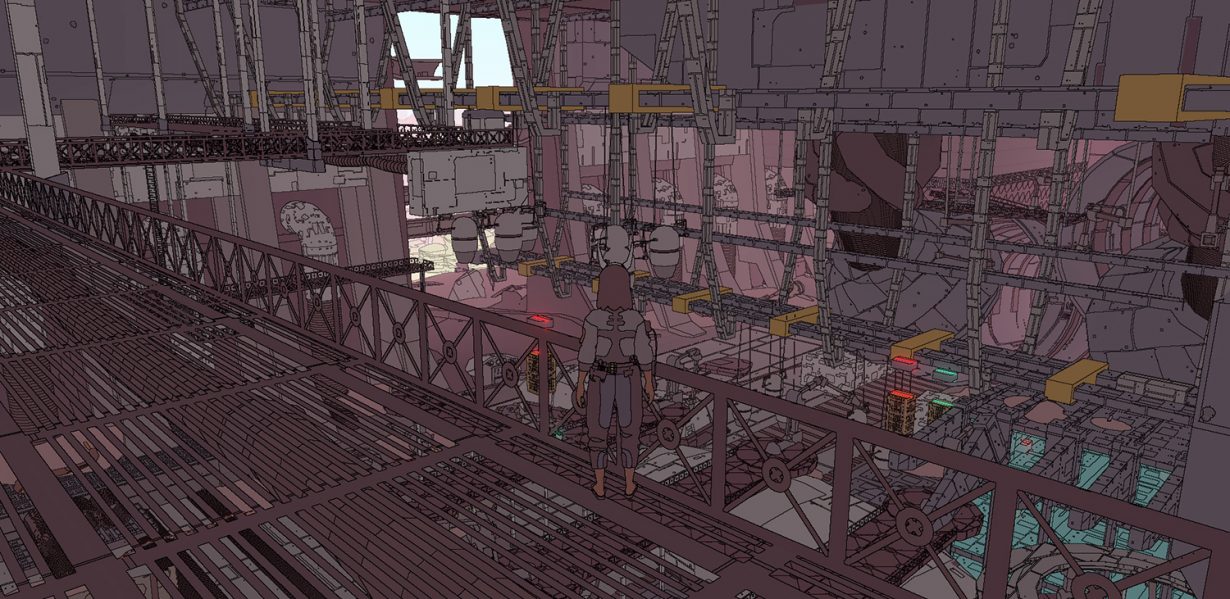

In the guts of one ruined starship, amongst tangles of rusted pipes and girders, thrums the aura of history. The ship’s structure is made of a complex, variegated metal, in contrast to the uniform sand dunes which surround it. Inside, you find a ghost – a hologram flickering blue. Their name is SARIN, a ship AI, who shares with you the last recordings of those that came before.

Later on I discover the starship’s name – the ‘Centre of Brunswick’. Immediately, my mind is sent reeling back to Earth, to outside the game itself. To the Brunswick Centre, a brutalist monument in the centre of London. Back in Sable, I find more names of other ancient spaceships – ‘Trellick’s Pillar’ and the ‘Balfron Connection’, both references to the high-rises of Ernö Goldfinger, two of Britain’s most famous brutalist buildings. There are others too: ‘Rowley’s Way’ (better known as the Alexandra Road Estate), the ‘Dunboyne’, and even the ‘Shadow of Neave’ – a clear nod to Neave Brown, the architect of these two concrete estates. Add to this the game’s three trading outposts: Burnt Oak, Seven Sisters, and Marrow Bone (Marylebone), after the London Underground stations.

Sable’s world, the desert world of ‘Midden’, is of course lightyears from London, but the historical connection seems important. More than a simple Easter egg. The starships of Earth are ancient, forgotten, and looked upon by the people of Midden as little more than the carcasses of ancient creatures, as ‘Whales’. Sable moves beyond the usual post-apocalyptic tropes, and past even dying earth narratives like those seen in Gene Wolfe’s sci-fi quartet The Book of the New Sun (1980-83), where spaceships have become citadels, and historical context is purged from the world by the long extension of time.

Time is everywhere in Sable. As you speed through Midden’s canyons on your jetbike, vivid bands of sedimentary rock are ever present, in each and every boulder, stack and cliff side. These chromatic rings and ribbons are a constant reminder of the presence of deep, geological time. Like cake layers, the strata of Sable’s world is differentiated only by the existence of man-made things – crashed starships, ancient observatories, hubristic statues the size of titans.

If the Anthropocene is the modish term for our current geological epoch – encompassing the significant impact we humans have had on the planet’s ecosystem, and its fossil record – then Sable’s Midden is a kind of post-Anthropocene world. One that has everywhere been touched by us, but retains the chance for hope and renewal. I can imagine the rocky layers littered with the debris of spaceships, of microplastics and nuclear waste. But Midden is also a planet in recovery. While much of what you do in Sable – delving into crashed starships, exploring ancient ruins, walking the bones of extinct megafauna – is thoroughly archaeological, there are just as many places where you’re tasked with repurposing the bones of the Anthropocene. Ruins in Sable are always to be used, not just melancholically pondered.

In the rubble and wreckage, you’ll find ‘Cuts’ – Midden’s currency – made from the harvested metal of spaceships. You’ll also assemble and cobble together various kinds of scraps, including parts for your jetbike. The ‘Machinists’ of Sable’s world are particularly enthusiastic salvagers. To them, technology, like a bike, already exists – the form takes place after you find the pieces and rearrange them into something new. ‘Our bikes are reborn in the ruined ships, in fragments spread apart,’ explains the machinist Sizo.

When I think of Sable, I think of salvagepunk. A kind of sub-genre of post-apocalyptic fiction, theorised by fantasy and sci-fi author China Miéville and writer Evan Calder Williams. Salvagepunk is all about recycling and repurposing the rubbish of capitalism. Like our own world, Sable’s Midden is scattered with our junk – a world recovering not just from one apocalypse, but likely many. We pick through the leftovers, with little idea of what these things once represented. Historical context has worn away like the surface of a weathered rock. But none of that matters now. The old world is done, and with Sable, it’s time to build something new.