How indentured labourers and their descendants might navigate the long and winding road back ‘home’

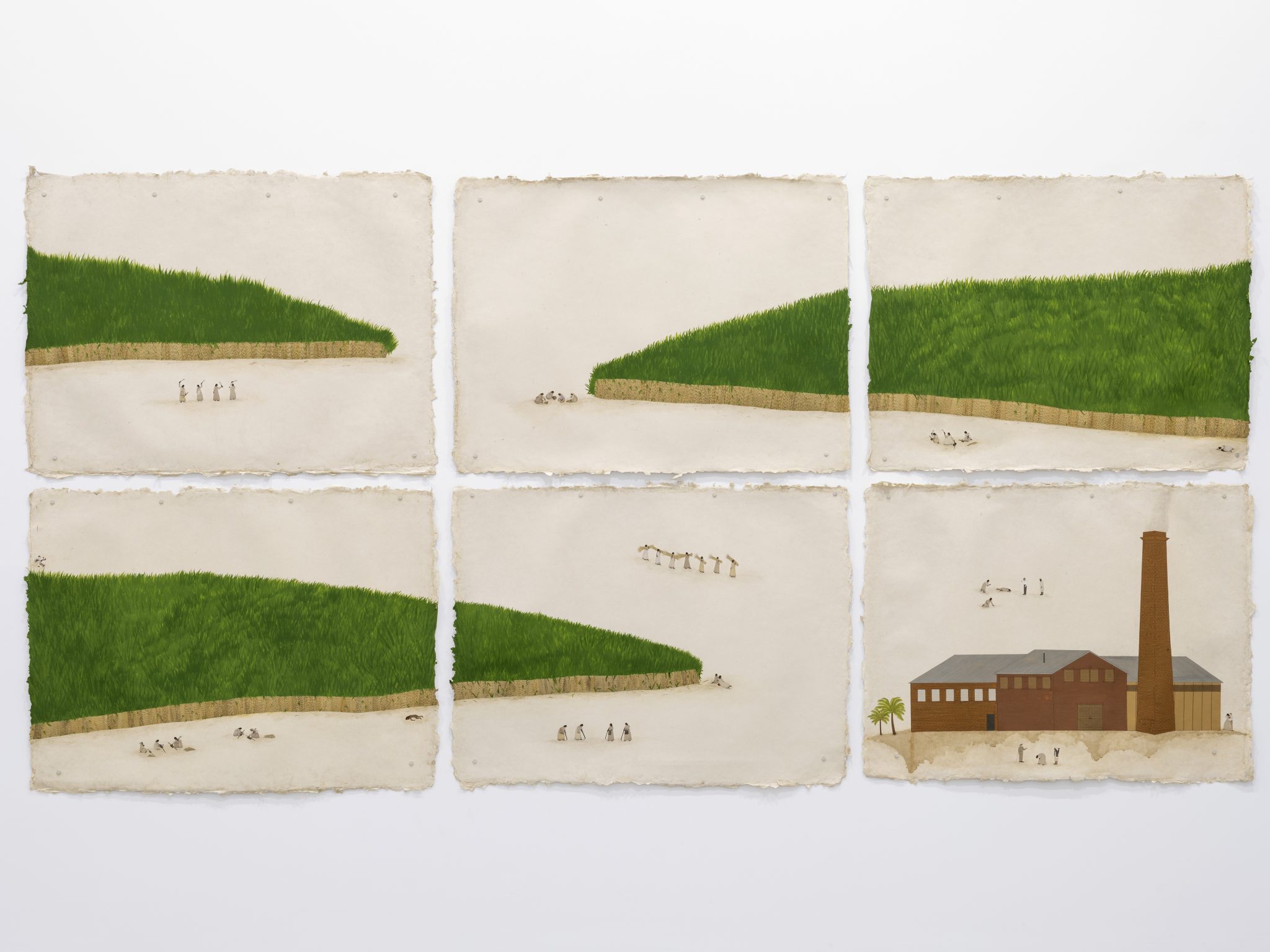

Sancintya Mohini Simpson is a first-generation Australian. She’s an artist. And a poet. And mixed race (Anglo-Indian). And, on her mother’s side, a descendant of Indian indentured labourers sent to work on the sugar plantations of Natal, part of present-day South Africa. Her watercolour painting Woman of Indenture no. 3 (2018) features a sari-clad woman, alone at the centre of an empty sheet of wasli paper (a tenth-century invention from Mughal India, traditionally used for miniature painting). She’s bent almost double, poised to hack into a sugarcane with a machete. The bottom of her white sari is dirty and stained. She floats on the page, floats in space. In the middle of nowhere. It’s part of a series of paintings executed in the flattened style typical of traditional Indian painting that map out the working conditions of labourers in Natal and their transportation across the ocean to get there.

Yet for all the apparent and overwhelming abjectness of this representation, there are some forceful countermoves. Where the Rajput and Mughal painting styles were slowly Europeanised (with appropriate forms of perspective, for example) into a style that became known as ‘Company Painting’ (because the patrons – the people who then held much of India’s money – driving influences on such works were employees of the East India Company and its equivalents) during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, here traditional Indian techniques are reclaimed. Taken back by a descendant of those who were taken away, displaced from their homeland and their culture. Do moves such as Simpson’s redeem what was stolen? Probably not. But perhaps it is a start.

Indentured labour became the primary labour source for colonial plantation owners once slavery was abolished throughout the British colonies ‘around the world’ in 1834. Prior to that, people from the southern part of the Indian subcontinent had made up 50 percent of the slaves across the Cape (largely today’s South Africa). And while many Indians ‘agreed’ to become indentured labourers, their main motivation was to escape the poverty and famine that were widespread in their homeland, thanks in the main to the actions of their colonial rulers. The effect of the colonial era and the indentured labour that it encouraged is the deepest historical root of the Indian diaspora as it exists today. And the main attraction in bringing Indians to Natal (where over 150,000 indentured laborers ended up) was because their labour was so cheap. When it comes to South Africa, the practice was stopped in 1911 (by the colonial government of India), ostensibly because of the poor conditions suffered by the workers in Natal, but in practice because it was suffering from a diminishing profitability and the British were far more concerned about rising Indian nationalism and the consequent threat to the ‘jewel’ in their crown. Everything was played out according to colonial logic and colonial rules. Fundamentally that’s a way of thinking that shamefully continues to inform the conditions and pathways of much migrant labour today, from East and Southeast Asia to the Gulf states and far beyond.

The show is titled ām / ammā / mā maram – am and ma maram meaning mango and mango tree in Hindi and Tamil respectively; and amma, the word for mother in Tamil and many other languages of the subcontinent. It’s a kind of diasporic linguistic mishmash. For although the history of migrant labour is one that is told in a multitude of languages, those languages are one of the first things of which labourers arriving in a distant land are stripped.

“I’ve realised that my practice has been very much for my mother or for the women in my family,” the artist says. Her mother heard her mother and grandmother speaking Tamil and Telugu, but wasn’t taught it herself. School meant English, meant Afrikaans. “I think there’s a sense of loss about that,” Simpson continues, “especially with identity for her as well.” Simpson’s Tamil pronunciation is, in her words, “terrible”.

When she returned to visit South Africa with her mother, the artist recalls that she was told that they would be able to find her mother’s childhood home because of the two mango trees growing in the garden. Mango trees that, like her mother’s ancestors, probably came there from India. But these stories are often hard to trace backwards. Memories are, for the most part, static; places change. Recalling her visit to South Africa, the artist remembers her mother talking about her recollections of beaches that were no longer accessible and markets that have moved. “It’s strange experiencing a place someone’s talked about for so long and then to find it and learn that it’s not still there.”

Simpson also recalls that when her mother was trying to prove her ‘Indianness’ in order to claim an overseas citizenship visa (a type of ode to bureaucratic exile), they found a copy of her uncle’s birth certificate (which stated that, even then, in 1954, he was ‘free or indentured’) and used the identification numbers listed on it to trace the ‘ship list’ on which her ancestors were transported. The numbers corresponded to details of caste, village and region. Things that, the artist recalls, weren’t really talked about within the family, for fear of what people might say and how they might be judged. The ship lists were carelessly written by the British and further information was hard to find; the pair eventually made a trip to India to see if they could reconnect to places, but what Simpson was left with was a series of gaps, a lack of representation in the archives and a picture that wasn’t complete. And thoughts about how those gaps might be filled. And most of the gaps with which Simpson is dealing relate to the stories and histories of women. “It’s about acknowledging these histories,” the artist continues, “creating space for discussion, rather than having shame surrounding them. But that acknowledgement also allows current descendants and generations to be able to move forward in positive ways.” The question, of course, remains how to reconstruct these histories when the traces of them are so faint and absent. How do you get from a lazily created ship list to the voices of these women and the reality of their lives?

‘Women outside the mode of production narrative mark the points of fadeout in the writing of disciplinary history’, the academic and pioneer of subaltern histories Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak begins her celebrated 1985 essay, ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’ One way of looking at Simpson’s practice might be as an attempt to create some kind of fade in. And in a language that’s somewhat more immediate than that used by academics.

Simpson’s new show comes with a poem written out in English:

Are our mothers

Mango trees

Or fruit

Fallen, slashed

Are they roots

Leaves or sap

Or branches we

hold onto.

In PICA’s galleries, the artist continues her exploration of the memories held in materials: black clay pots fired in sugarcane sawdust that marks and textures the vessels; two tables (made from scorched mango wood) measuring the length of her own and her mother’s body, objects that might conjure memories of the spatial arrangements of slave ship holds; scent made from mango leaves from her mother’s garden; paper made from mango fibres from her mother’s garden. All of which both trigger memories and mirror the migration of flora and fauna that was a part of colonial expansion. There are constituent parts of home that ‘travel’ with you. And part of this is a displacement of sorts – what is lost is conjured in objects, objects that might trigger similar memories or compatible sensations in an audience. When words alone, for the reasons previously discussed, might not be able to do the job.

ām / ammā / mā maram is on view at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, through 22 October