In Watch Movements at Patricia Fleming, Glasgow, the artist explores the threshold between artistic intervention and architectural decay

The mid-renovation site of the new Patricia Fleming gallery offers a fitting setting for Sara Barker’s latest exhibition: literally, in some cases, as many of her new works are site specific to recessed spaces within the walls and floors, or inserted into rectangular gaps created by removed sections of tilework. Barker’s work often occupies the borderland between painting and sculpture: pieces that start out (or so it seems) as abstract landscapes or dreamy figurative scenes grow thin metal limbs extending outwards into space. But the chance to work in, and into, a still-dilapidated network of rooms – part of a former police station and training centre built in 1895, more recently used for underground raves – has allowed the Manchester-born artist to move away from this and to explore the threshold between artistic intervention and architectural decay.

In a former shower room, tilework has been selectively removed, with other sections of the ceramic wall-surface coated in copper leaf. From a hollow in the floor a little metal tree sprouts, while a couple of the voids left by the wall extractions contain Watch Movements I–IIII (all works 2023), delicate arrangements of antique watch faces, suggesting branch or leaf patterns. In another set of rooms, an eye-level stripe of tiling has been removed from the walls, leaving a scratchy channel that the artist has filled with little bundles of wood and bent-wire curios, many, like Surround, suggesting skeletal floral forms. Once you spot these tiny interventions you start to assign aesthetic value to what might be random accretions of concrete fragments, little accidental smears of paint, fragments of desiccated duct tape that suggest a microscopic version of the gridwork pattern of the tiles. The point at which creative intervention ends is intriguingly tricky to fix.

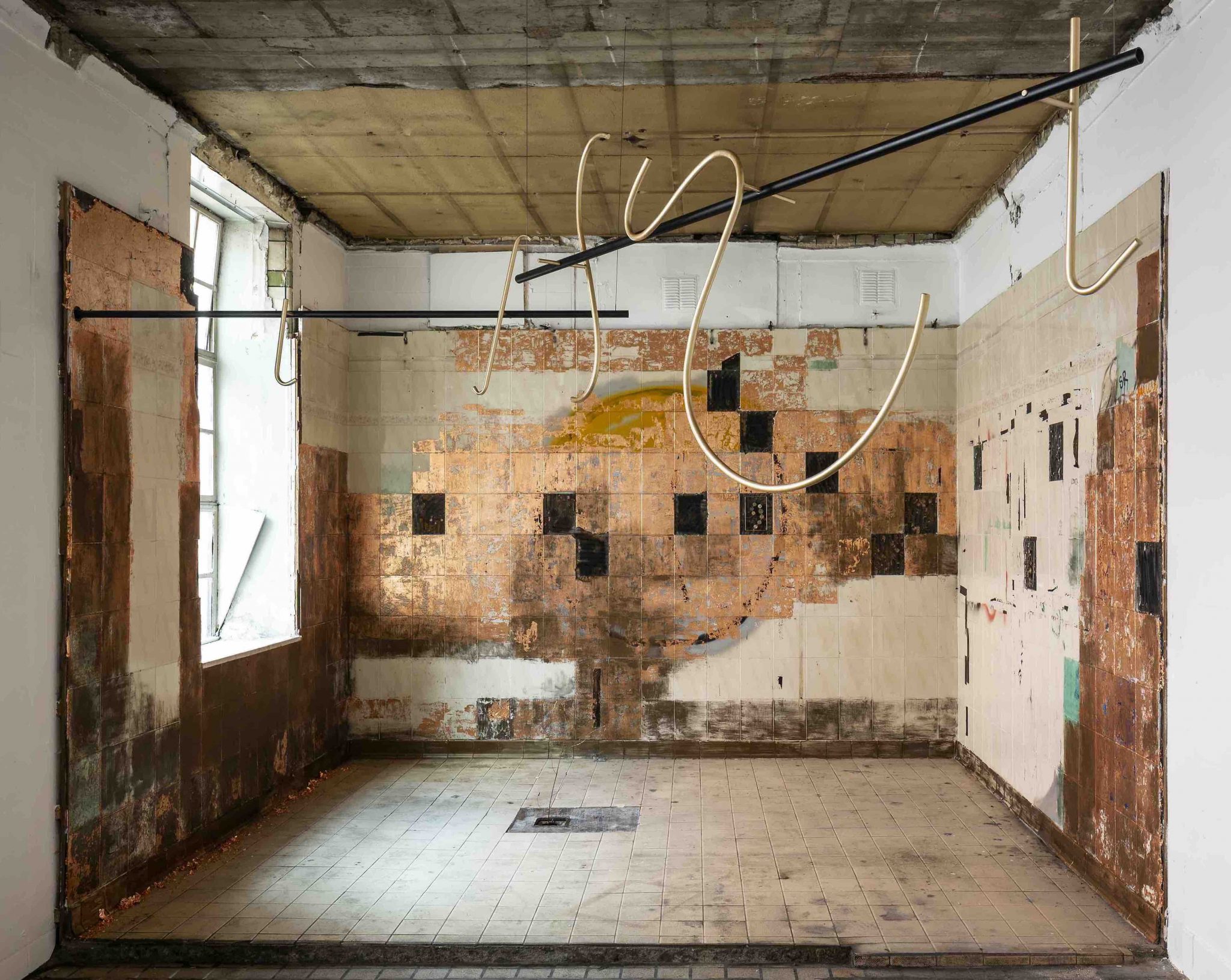

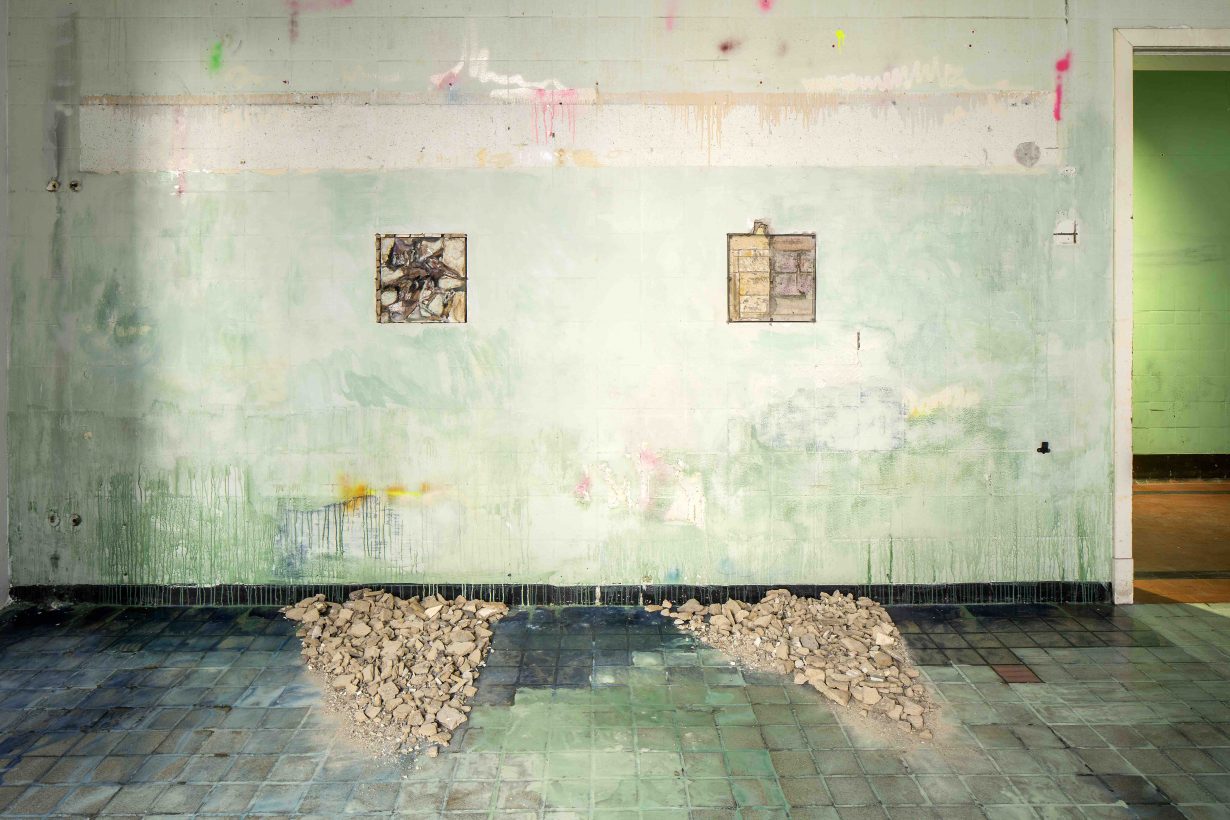

There are also works that slot more neatly into their physical boundaries, including various chunky reliefs like Oxford House and Cleft, created with rubble and ceramic shards extracted from walls and floors, combined with foil, paint and other materials, and bound with mortar to form rough, Dubuffet-esque friezes. The central space of one gallery is given over to Reenactment, a mobile of curved poles that sways gently in the breeze from an open window, some of the bends hinting at the dancing bodies that might previously have occupied these rooms. But these more conventional pieces are complemented by a setting imbued with a pervasive sense of aesthetic intrigue.

Many of central Glasgow’s grand Victorian and neoclassical buildings are in a perilous state, the city’s postindustrial decline legible in this architectural degeneration. Barker’s interventions convert one such building into a speculative cross-section of its varied former lives, sensitising us to the structure’s real and possible histories in the very act of aestheticising its decay. If anything, this might initiate conversations about the future of such sites, in a way that resists the easy answers of private capital.

Watch Movements at Patricia Fleming, Glasgow, 9 June – 16 July