The American artist melds performance, community and exchange in quietly subversive works that invite the collaboration of her audience

While watching a performance of American artist Sarah Pierce’s work Future Exhibitions (2013), as part of her ongoing retrospective, Sarah Pierce: Scene of the Myth, at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, one of the five performers came up behind me, placed their hand on my back and gently pushed me into the centre of the room. They carried out the same action on a person who’d been lurking in the doorway, the only other member of the public apart from myself present in that gallery to witness what was taking place. Up until that point, I’d felt more or less like a detached observer. Participation and inclusion are two central terms feeding the development of art institutions today, but whether these concepts function as buzzwords or the starting point for a genuine transformation of the museum is the subject of much debate. They are also key elements of Pierce’s work.

I’d followed the group of performers up from the museum’s mezzanine,

where they’d begun by performing another of Pierce’s works, Campus

(2011). I’d watched them stride purposefully and quickly through galleries housing other works by Pierce, such as the largescale installation Towards a Newer Laocoön (2012), which features an enormous plaster replica of the Ancient Greek sculpture Laocoön and His Sons that has undergone countless, debated restorations (this replica was gifted to Dublin’s National College of Art and Design in 1790 by David La Touche, a wealthy banker, and was used up until the 1970s to teach drawing classes at the institution, where Pierce is a teacher), surrounded by paint-splattered worktables strewn with rubble and newspaper clippings relating to student protests. Continuing though, the performers chanted unexpected slogans like: “It’s not just the seeing, you have to feel”, or “These kinds of structures need attention and finesse”. The group had paused for several minutes in a long light-filled corridor of the museum’s east wing to pull back and forth a series of large red square curtains, jumping in and out of the hanging fabric while stamping and making gestures associated with protest movements, such as raised fists, which in an Irish context correspond most recently with the ‘Repeal the Eighth’ movement leading to the legalisation of abortion in 2018.

Pierce’s quietly subversive and purposefully unorthodox exhibition involves an overlapping and eclectic mix of materials and forms of presentation. It represents 20 years of art practice that includes installation, performance, archives, talks, papers, workshops and the activities of self-publishing and teaching. References and themes in the exhibition are equally diverse and often intentionally difficult to fully grasp: the work and legacies of artists such as Kazimir Malevich and Bruce Nauman, the history of radical pedagogy and protest, Irish nationalism and the diaspora, new models for ethical collaboration. Linking Pierce’s varied work is a common motivation to disrupt the learned behaviours ingrained within the institutions of art, from the gallery to the academy. Placing the visitor off-balance and unsettling their habits is precisely the point. Pierce is attempting to destabilise how we’ve grown accustomed to viewing, interpreting, classifying and understanding art.

One performance melded into the next, as we arrived in a room painted black, with an adjoining room painted white. In both rooms various objects related to the making of exhibitions – such as picture frames, wooden plinths, wire stands, cardboard sheets, tubes, tarpaulin, Styrofoam and packing tape – had been stacked in carefully assembled sculptural forms and positioned around the space. This was, apparently, a separate work, Future Exhibitions: amidst the clutter, the performers read aloud from texts that seemed to offer accounts of a series of exhibitions that had already taken place. One read a description of what they said was a photograph of The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0,10, in which Malevich’s works were shown in 1915: “This is a photograph of an exhibition,” they began, “the paintings are hung in groups, salon style. Hung in the upper corner, near the ceiling, is a black square on a white canvas. On the floor, placed next to the wall, is a modest black chair.” Another gave an account they claimed was taken from the catalogue for the 1969 Conceptual art exhibition One Month, organised by curator Seth Siegelaub in his New York gallery. Hearing the texts being read, it was impossible to ascertain whether any of them was entirely factual. But given the straight-faced commitment of the performers to their delivery, that somehow didn’t seem to matter. As the performers moved slowly around the room, they adopted a series of different right-angle poses that appeared to be in dialogue with the geometric forms being created by the discarded exhibition objects. After being guided into the centre of the room, my fellow museumgoer and I were effectively added to the accumulation of materials making up this artwork.

But despite all the disruptions, dismantling and intentional confusion at play, Scene of the Myth doesn’t come across as a cynical attempt to pull apart and expose the false promises or pretensions of the artworld. Preserving some forms of inheritance, while resisting others, Pierce seems intent on encouraging the visitor to question how they should act or interact in the company of art and what the possibilities of the gallery space might be. For Pierce, that potential lies in what she has referred to as the ‘community of the exhibition’, a kind of unpredictable coming together of diverse people, histories and ideas that art seems uniquely capable of facilitating. It’s an optimistic view of art’s continued importance and relevance, and it makes me think about whether I had felt part of such a community during my two days visiting the exhibition. It’s been a long time since I engaged in as many conversations about an exhibition, its ambitions and difficulties, with as many people: from performers in the works, to invigilators, to visitors and other artists. In some ways, I have to acknowledge that I did feel part of something.

Pierce considers pedagogy to be an integral part of her work, rather than a parallel or lesser activity. Figures such as philosopher Hannah Arendt and the American Sociologist C. Wright Mills inform both her teaching and her artmaking. In ‘On Intellectual Craftsmanship’, the appendix to his most famous work, The Sociological Imagination (1959), Mills instructs his students to periodically dump their research files onto the floor, mixing up and reordering their contents. This allows, according to Mills, ‘fruitful developments’ and new forms of cross-classification to emerge.

One can clearly see Mills’s thinking at work in Pierce’s practice. Standard institutional conventions and protocols are often jumbled, reconfigured or abandoned. In the work The Square (2017), a large black square is handpainted on the wall of a traditional white-cube gallery space. Viewing the painted shape, Malevich is again evoked, but this square is even more wonky than some of his iterations of the shape. A museum bench is positioned in front of the square, a conventional frontal viewing arrangement to encourage visitors to sit and spend time looking at it. Nowhere in the room are details pertaining to the circumstances of the painted square displayed, and it’s only by reading the zine that accompanies the exhibition that we learn that it was painted by a group of workshop participants. The collective act of painting the square is, according to the text, the starting point for the development of a ‘play without a script’, inspired by Bertolt Brecht’s experimental Lehrstücke ‘learning play’, consisting of unspecified chants and gestures, and to be performed without an audience. Here, in this mostly blank room, which is also apparently a theatrical stage for a performance we will never see, we are left with questions – not least, ‘what am I supposed to make of this?’

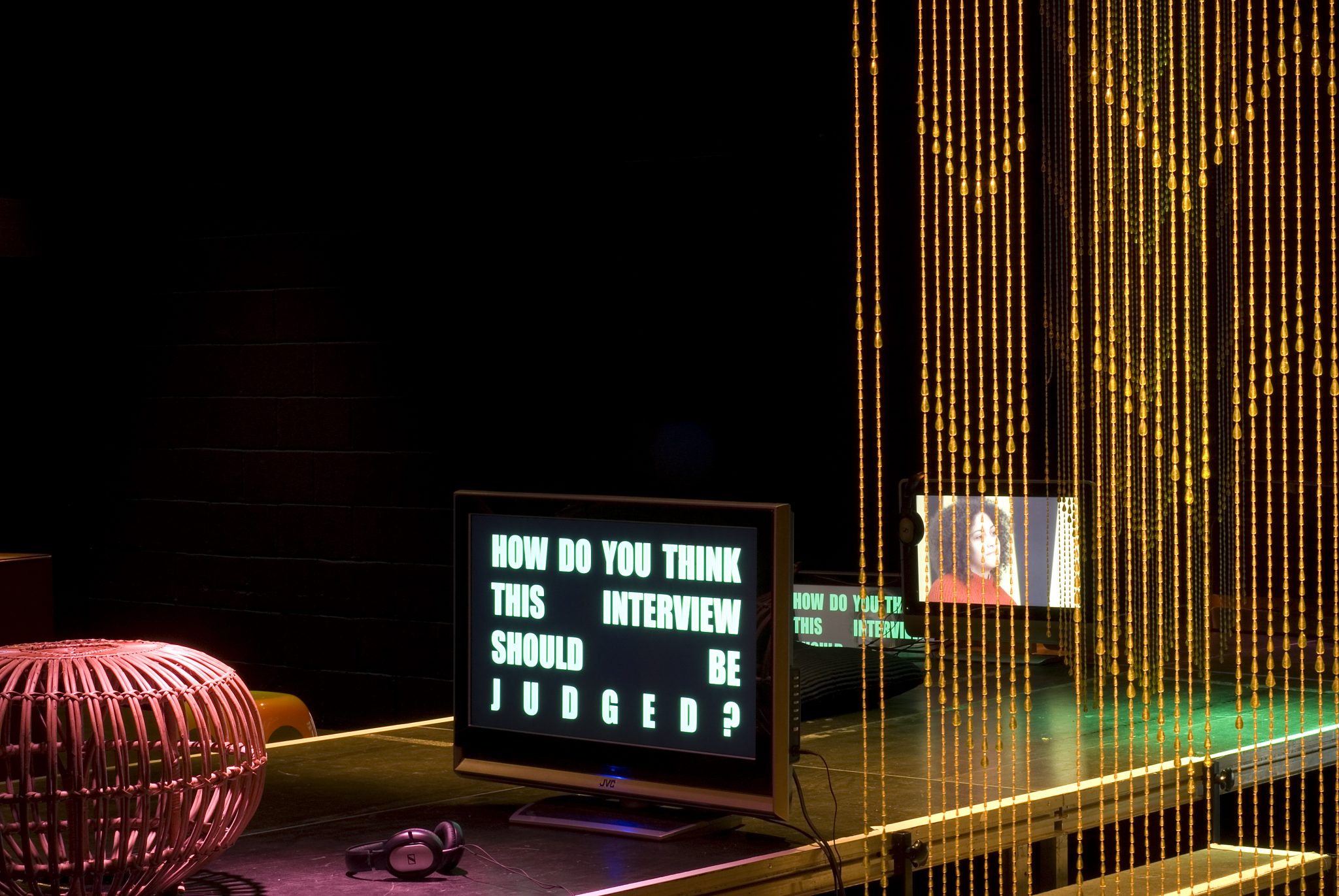

This encouragement of questioning without explicit or authoritative guidance is an underlying ethos of Pierce’s project, as is the restaging of other artists’ works and the reexamination of art-historical legacies. In An Artwork in the Third Person (2009), Pierce references a videowork by British artist Kevin Atherton entitled In Two Minds (1978), in which the artist engages in a tongue-in-cheek question-and-answer session with himself on the topic of making and exhibiting art. Pierce borrows Atherton’s questions, using them to interview a group of students, firing questions at them in quick succession. “What is this about?”, “Are these questions difficult?”, “Are exhibitions the same as theatre?”, “Where are you going as an artist?”, “Does an artwork change when it’s remade?” The questions flash up intermittently on a series of eight flatscreen monitors in brightly coloured text set against a black background, all of it staged within a black cube with theatrical props and lighting. On each screen, we see a closeup of a student’s face, capturing all the hesitancy and insights that result. Attached to each monitor is a pair of headphones and in front is placed a small rectangular piece of carpet that invites the viewer to kneel or sit and listen to the students’ thoughtful and carefully considered responses, despite the speed of the questioning. “A performance,” one student muses, “if it is in front of an audience, needs to have that exchange, it doesn’t mean that its ready or completed, but without that exchange, you don’t know how it works.” Another offers: “Sometimes it doesn’t matter if things are true or not, just the fact that people relate to them as such makes them true.”

Precisely what kinds of knowledge and forms of community might emerge from the encounters that Pierce stages, both within and beyond the gallery space, are not always clear. The artist seems genuinely comfortable with this uncertainty. Her wager is that it’s this unpredictability and disorientation that provide the conditions for new forms of dissent and self-determination to be generated. That leaves open the question, however, of whether the various exhibition visitors, performers and workshop participants involved feel equally comfortable with this experience of uncertainty. My discussions with the museum invigilators revealed that they’d been receiving fewer information requests from visitors than usual. Viewers, they said, seemed to be comfortable “just to get on with it”. Indeed, one group of visitors had apparently taken down and reordered all the items on the shelves of Pierce’s work Affinity Archive (2000), a collection of objects, including magazines, scripts and informal artworks, donated to Pierce by other artists, writers and curators; another group had repositioned all the carpets in the installation An Artwork in the Third Person. Despite the exhibition’s sometimes confounding nature, from my observations, the visitors to IMMA appeared at least willing to engage, discuss and think about what was being presented to them. They, like me, seemed to navigate the exhibition as they chose, even after a push, remaining open to what the works might offer, deciding if they wished to investigate further, determining which questions to take up and which to leave unanswered. At a moment when museums and institutions are rethinking how they’re organised and run, Pierce’s interventions may not present any straightforward solutions, but they do invite audiences to ask themselves what role they might want to play in that process.

Sarah Pierce: Scene of the Myth at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, through 3 September