Not here

Throw open the windows of Galeria Jaqueline Martins, look across the street and see the letters ‘aqui’ appended to the housing blocks opposite. The ‘a’ graces the window of an apartment on the same road; the rest of the word is on the back of a building located on the street behind, just visible through a gap in the otherwise crowded architecture. This long-term architectural intervention by Renata Lucas is one that frustrates purposefully. ‘Here’, it says, in its native tongue. Yet when one stands on the site of ‘here’ one cannot view the work: one can only appreciate it at a distance, over there.

I’m here – aqui – in Centro. Praça de República, the palm-laden square that forms this area’s epicentre, has become a home-from-home ever since I arrived on my first visit to São Paulo six years ago. It’s a recent novelty, however, to be able actually to see art around here. The galleries have come, as have new bars and restaurants. Yet gentrification in São Paulo is never a foregone conclusion. The botecos and kilo buffets do brisk business alongside the newcomer eateries. Still, the prostitutes work R. Marquês de Itu. Still, the city’s homeless congregate in tents, around fires, playing chess, lounging within this rare oasis of foliage in an otherwise concrete jungle. As the weekend wears on, the streets get a bit more shifty – a result of the new city mayor’s attempts to ‘clean up’ nearby Cracolândia and its community of drug users. The residents are momentarily dispersed, but they’re still here.

Afros, the 1980s and being there (or here)

Inside Martins’s gallery Ricardo Basbaum has a solo exhibition of work from the early 1980s to mid-1990s. Basbaum is associated with the Geração 80 group, named after the 1984 group exhibition Como Vai Você, Geração 80? (How Are You, 80s Generation?) at the Parque Lage art school in Rio de Janeiro. Yet while the official art-historical narrative of that generation – Basbaum’s peers include Beatriz Milhazes, Leonilson and Barrão, who came of age during the emergence of Brazilian democracy – highlights an almost postpolitical identity in which art is primarily a mode of self-expression as opposed to a form of social consciousness, Basbaum’s sculptures, drawings, photographs and actions see the artist tie self-affirmation to the notion of the (still) political subject. In the first of two rooms, the walls are painted in pastel blocks. On each a different ‘manifesto’ is painted, typically a single line, or line repeated, written in the first person: ‘I re.fuse’, the artist states on a background of yellow. ‘I am against’, he repeats 22 times against a wall of pink.

Much of this work falls under Basbaum’s ongoing project ‘New Bases for Personality (nbp)’, initiated during the 1990s, which the artist describes on his website as a ‘general motivation or pretext for work (almost a program of action), a means for impregnating space’, implemented under the subheadings of ‘immateriality of the body’, ‘materiality of thought’ and ‘instant logos’. In the gallery, this is materialised in the form of diagrammatic wall drawings that refer to the artist’s own body; a cagelike steel-mesh ‘capsule’ sculpture with two seats inside (a work that also harks back to the participatory legacy of the previous generation: Lygia Clark, Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Pape); and video documentation of Basbaum’s 1987 ‘eye’ project, for which he designed a pseudo-corporate eye, distributed across São Paulo (in the form of stickers) as a means to interfere with, or brand, the external world (in the vein of the modern pixação tags sprayed in spidery, heavy metal-inspired calligraphy throughout the city). Basbaum’s work can be dense, academic, at times to its detriment. But at its most accessible – of which type there’s plenty on show here, such as Untitled (1989), a photomontage of the artist varying the manner in which he styles his afro, accompanied by Cabelo (Hair, 1986), six drawings on paper of irregular forms made up of curling scribbles in Indian ink – it can be thought of as something akin to conceptual self-portraiture, through which the artist explores his own subject. ‘I am here’, it cries.

A whole lot of absence

Presence – or rather the notion of presence highlighted by an absence – is also a running theme through a group show staged a few blocks away in the Biblioteca M.rio de Andrade. Curators Jacopo Crivelli Visconti and Olivia Ardui have installed mostly international works, many of them by canonical artists, including Guerrilla Girls, Hans Haacke and Mario Garc.a Torres, across two rooms of the art-deco building; both art objects in their own right, and documentation of performances past. Central to Acordo de Confiança is Helmut Wietz’s video recording of Joseph Beuys’s performance I Like America and America Likes Me (1974), in which the Fluxus artist travelled to New York, was stretchered to the Reneé Block Gallery and spent three days incarcerated there with just a wild coyote for company. The work has been interpreted and reinterpreted constantly within art history, but we can consider the position of Beuys as both absent and present. ‘Absent’ from America – in that the artist didn’t physically ‘set foot’ on us soil – but present in the gallery. If so much of Brazilian art has historically featured the active artist, or the activated art object, it is the absent artist, or the absent art object, that is central to this exhibition. Is presence – a thing, a material gesture, obvious labour – prerequisite for artmaking? Further historical works (the show, otherwise an education in early Conceptualism, also features contemporary names such as Maria Eichhorn, Alessandro Balteo-Yazbeck and Maria Loboda) demonstrate that it is not, and has not been for some time. Works on show range from 5 Telepathic Pieces, by Robert Barry, in which a handwritten note from the artist to a curator describes how the artist will psychically ‘transmit’ highly ephemeral ‘works’ for a 1969 exhibition in Vancouver (one of the works will apparently manifest itself as ‘particular emotions’; another consists solely of a ‘secret desire’), to Ian Wilson’s There was a discussion with Lawrence Weiner in New York City (walking up 6th Avenue to Kosuth’s place) (1968), in which the event described is only evidenced through the work’s title typed on a piece of plain paper, installed here in a glass display cabinet, and September 15, 2009 (2009) by Alfredo Jaar, an envelope, apparently containing a photograph of Karl Marx’s grave, with a note from the artist stipulating that whoever buys the work may only take the photo out to look at it once a year.

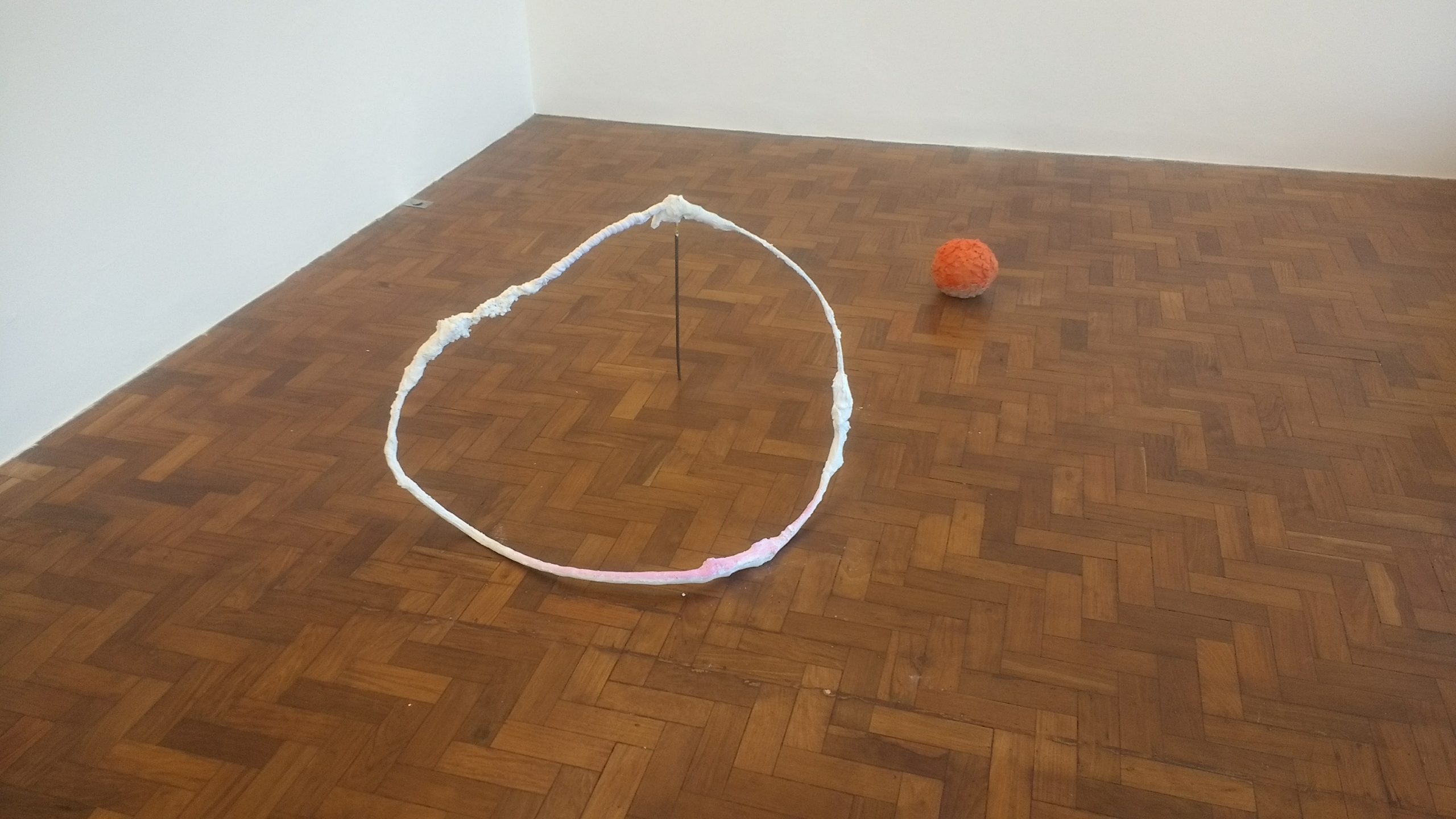

A large knobbly hoop

Holes are a preoccupation of Daniel Albuquerque (do I need to point out that a hole is the presence of absence? Well, you can never be too sure). Oral is the young Rio-based artist’s exhibition at BFA São Paulo and comprises loose-woven wallworks, each with a painting semivisible behind (a little less coy than Jaar’s photograph, but only slightly), that look down upon delicate floor sculptures of messily combined industrial materials.

Daniel Albuquerque. Photo: the author

Daniel Albuquerque. Photo: the author

Bandage (2017) is a large knobbly hoop consisting of built-up polyurethane, plaster, fabric and cement massaged and manipulated by Albuquerque, painted in white acrylic and propped up at an angle by a steel rod. Dashes of spraypaint (sickly fluorescent pink) dart across the sculpture’s surface. This hoop, depending on one’s perspective on the work, either frames the gallery’s parquet floor or Sunset Bazooka (2016), a 20cm-diameter orange-and-yellow-spraypainted ball of cement, likewise rough and lumpy, installed a metre or so away. The exhibition text describes the works as having ‘sexual nuance’. Perhaps that is going too far, but Albuquerque’s labour, and by extension his body – contorting to manipulate his materials, his hands mucky – can be felt throughout the work. In every detail of the sculpture, the artist is present.

Relief

I travel by subway to the leafier, wealthier Jardins area for a varied trio of painting shows, which range from the austere, self-reflexive works of Valdirlei Dias Nunes at Casa Triângulo, to the rich, densely textured canvases of the late Maria Leontina at Bergamin & Gomide. Hovering somewhere between the minimalist and maximalist is Rodrigo Andrade at Galeria Millan. There is a lot of work here and, given the amount of the material piled onto each mdf surface, a lot of paint used. Approximately half the 30 works on show feature just two colours, used in compositions of flaglike simplicity: Untitled (2017) is typical, in which half of the 20-by-25cm MDF sheet is covered in yellow oil paint, which crashes, with a thick impasto curl, into the dark blue paint that pervades the remaining half. The rest feature strange cartoonish characters, simply rendered, but likewise with an excess of paint: a girl with straggly hair, a silhouetted and mournful-looking ogre. The latter stares at a white cloud. This uncomplicated formalist – and joyful for it – painting resists any great critical interrogation bar the acknowledgement of Andrade’s impressive paint handling. Dias Nunes’s work is likewise simple, but to such an extreme that Recent Paintings and Reliefs invites the viewer to ponder questions concerning framing and deconstruction, infinity and existence. This is a monochrome show in which roughly half the paintings are uniform matt black with a golden yellow grid painted over the top. In some of the grids, the artist has left an irregular gap. It’s an absence within the composition that draws my eye, a black hole through which the viewer is sucked, a simple formal gesture that leaves us contemplating nothingness (and being). The ‘reliefs’ of the exhibition’s title are mostly painted (white enamel) sheets of MDF, framed with pale cedarwood. Sections of the latter, however, have been either removed or extended beyond the white composition. Likewise, for me, this neat move gives rise to questions of physical and metaphorical edges, mental borders and external control.

Identity politics

It would be nice to say that Leontina’s work follows the neat abstract turn from early-twentieth-century figurative Modernism to mid-twentieth century Concretism. In truth the artist, who died in 1984 (in her late sixties) yo-yoed back and forth between both movements – as this excellent exhibition demonstrates. Natureza Morta, from 1948, is, as the title states, a still life, rendered in peach, pale orange, murky yellow and reddish browns, depicting a coffee table complete with cups and saucers, water jug and fruit bowl. Yet while these objects are identifiable as such, there is the beginning of a fuzzy kind of geometric abstraction in their composition. Blocks of paint divide up the canvas, such that the viewer is drawn to consider this formal device as much as the ostensible subject. One can see the leap from this work to a painting such as Os jogos e os enigmas (1954), a roughly painted deep and dense red-and-green jumble of rectangles. The walls on which some 30 of the artist’s paintings are hung have been painted a variety of colours, picking up on Leontina’s typically dark, warm palette. It’s an unnecessary, annoying curatorial device, though one that ultimately (and happily) does not detract from this vital exhibition. Leontina’s work has never received its just recognition – thanks to old-fashioned (or not so old-fashioned) sexism, her career was largely overshadowed by that of her husband, artist Milton Dacosta – so one hopes this show might go some way towards raising her profile.

A diagonal groove and the prospect of jail

The walk to Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel, high on the hill of R. Fradique Coutinho, is always a bit of an effort. The road is steep and, because each property owner in São Paulo is responsible for the patch of pavement outside their building, in changeable states of repair. And though the gallery’s architecture is a pristine white cube – walls freshly painted, features attentively designed – it houses a series of ruins. Declive, one of four works from 2017 making up Manoela Medeiros’s show Swept Dust, mimics one’s walk to its venue. Five concrete steps protrude from the wall, a partial floating staircase that leads nowhere. There are a further five chiselled rectangular gaps in the walls, as if more steps are to be added, or perhaps evidence of steps that were there, but have since disappeared or been removed. Six concrete pillars, each with diagonal grooves carved into them, stand in the middle of the gallery: impotent and useless, holding up nothing. This exhibition-in-a-state-of-disrepair is completed by the artist’s removal of the plaster in two sections of the gallery’s wall, appending it to the wall alongside the respective excavations. The allusion to ruins, the slow, melancholic disappearance of something – and this, admittedly, is me projecting onto the artwork as opposed to being led by it – chimes with Brazil’s political situation right now. The slogan of the Worker’s Party during the 2000 elections was ‘São Paulo Dá a Volta por Cima’ (‘São Paulo rises from the ashes’). During the run of this show, Lula, the former Worker’s Party president, wildly popular during his time in office (2003–11), was convicted for accepting bribes and now faces jail. The hope of that period feels absent now, as increasingly assiduous policing reveals more and more corruption every day.

On the bright side…

It is hard for architecture not to become a reference at Galeria Leme, across town, located next to a busy road in Faria Lima. The gallery, designed by Paulo Mendes da Rocha, is a cleaned-up brutalist cuboid, the 1sqm concrete blocks used in its construction left plain and unpolished, their joints combining to create a gridlike-effect on both the exterior and interior of the gallery. Here are four works by Osmar Dalio, who is taking part in his first exhibition after a 17-year hiatus. These are hulking, angular, multifaceted Corten-steel sculptures ostensibly made in the minimalist tradition. There’s something grimy and nonprecious to them, however – little lines of rust speckle the gallery’s gleaming floor – they feel like elements of the building that have fallen, perhaps Tetris-like, to sully this meticulously designed space. One, Planar III (2016/17), uneasily balances at an angle. In a way, describing these works is similar to describing the city that hosts them: messy, pragmatic, decaying and yet, despite all this, still possessed of a certain elegance.

Oliver Basciano is editor (international) of ArtReview. This article originally appeared in the September 2017 issue of ArtReview

Osmar Dalio. Photo: the author

Osmar Dalio. Photo: the author