A people living under dictatorship stand fundamentally distanced from their government. The populace is not only disenfranchised, but also cut off from any means of defining its own society. Dictatorial authoritarianism will penetrate culture, commerce, family life and all the other means by which individuals construct a society. While the ‘leader’ appears to embody the society, he is in fact keeping himself apart from society, often using violence or the threat of violence to keep these boundaries in place.

Artur Barrio spent much of his early life living under a dictatorship. So perhaps it’s no surprise that ideas of what it means to be an outsider or on the periphery are central to his work. And that despite the fact that he is now represented by a commercial gallery in São Paulo, that his CV includes biennials, museum shows and major awards, that he lives in a comfortably furnished flat in Rio de Janeiro and that he has a sailing ship to further his interest in diving, the artist continues to cast himself as an outsider.

The consequence of an early life in which oppressive regimes – ones that fragmented and divided the society he lived in – seemed to follow him around

This is not a piece of subjective role-making, however, but the consequence of an early life in which oppressive regimes – ones that fragmented and divided the society he lived in – seemed to follow him around. In 1952 his politically progressive father emigrated, with his young family (including seven-year-old Artur) from Portugal to Rio de Janeiro (where they arrived three years later by way of Angola), in order to escape the authoritarian Estado Novo regime. Nine years after the artist settled in Brazil, that country’s democratically elected government was felled by a dictatorship too. Barrio himself doesn’t like to talk about this formative time. “I don’t want to take advantage of the history,” he tells me through a translator. “I don’t want to use it as marketing.” Yet from the outset his work, if not always expressly set against the political authorities, of necessity had to circumnavigate them. The most significant consequence of this was the artist’s almost exclusive use of public space to present his early works, among which are sculptures made from impermanent materials intended to be found by passersby, and various open-air performances and anarchic ‘actions’, some of them documented, others left in the memory of their author alone. “It wasn’t that I was necessarily looking for a wide audience, but going to these places meant working with new boundaries, new limits and new types of interaction between myself and the public,” he explains.

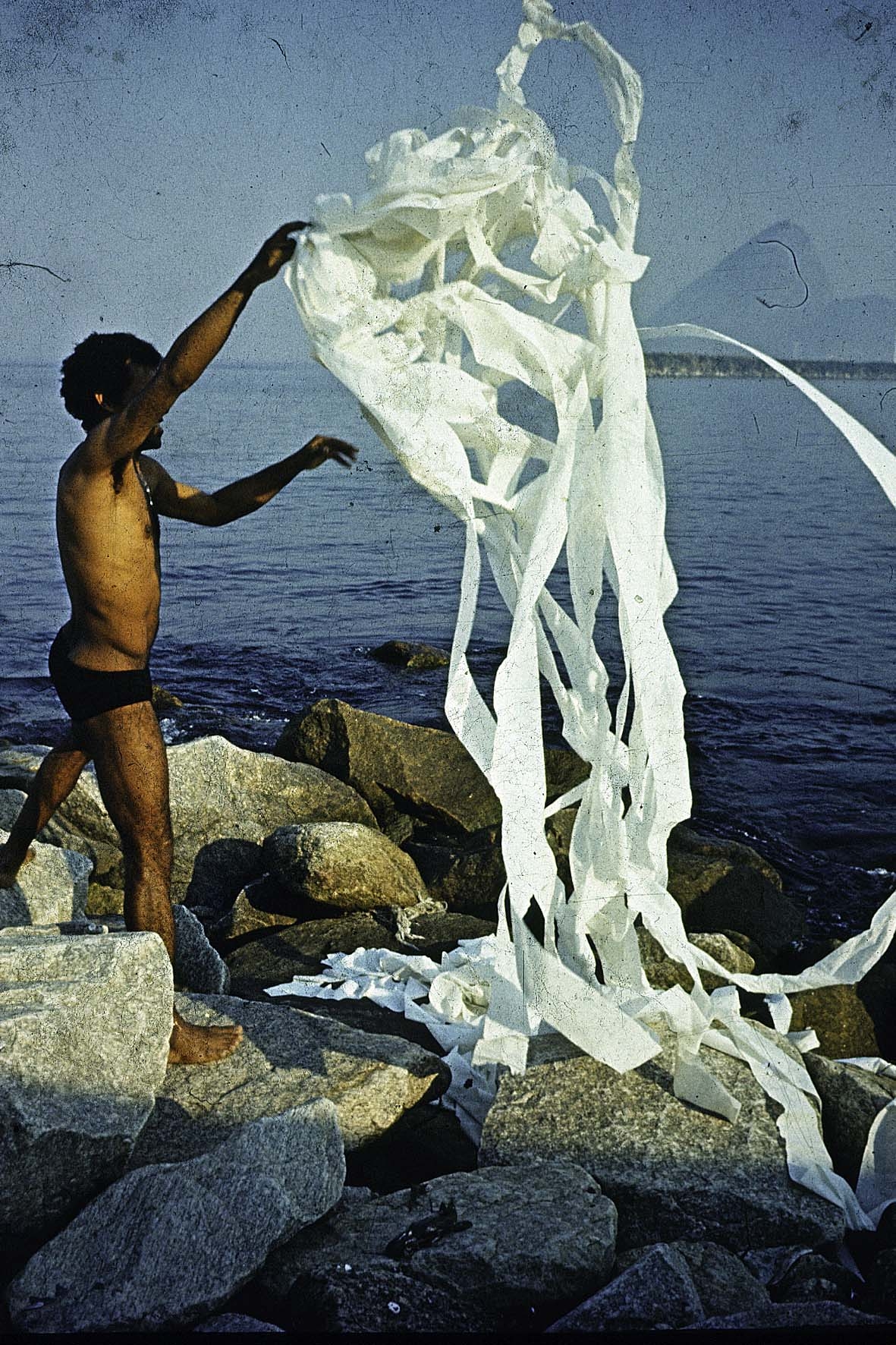

P…H… (1969) – a performance in which the artist, stripped to his trunks in the gardens of Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro, threw armfuls of toilet paper into the sea – is a rare occasion when Barrio got close to an institution (though it’s telling that he never entered the building and remained on the periphery of the property). Even if the toilet paper almost instantly disintegrated and was washed away, there is photographic documentation of the work. 4 Dias 4 Noites (4 Days 4 Nights), on the other hand, remains entirely undocumented and without any record of its even having had an audience. In May 1970 Barrio walked the streets of Rio for four days and four nights, not stopping for food or rest, and without any planned route or destination. While he has recounted his increasingly hallucinatory memories of the performance – interacting with the people and places he passed by – no images or firsthand spectator reports exist. What the work did engender, however, is a change – catalysed by sleep deprivation and hunger – in terms of the way in which the artist perceived his surroundings. The assumed reality of the surroundings was broken up, rewired and undermined by the tricks his mind played on him. Indeed, this idea of rupturing preconceived assumptions is one of the enduring aims of Barrio’s work. Where 4 Dias 4 Noites was an entirely personal experience, the works that brought the artist to greater prominence within the generation of artists – among them Antonio Manuel, Cildo Meireles and Lygia Pape – that came to attention during the late 1960s and 70s were the sculptural bundles he left in the streets for as wide a public as possible to stumble across. In 1970 the artist distributed no less than 500 of these ad hoc sculptures around Rio, a series he titled Situação (Situation). The aim of these works, made from stained blankets, meat, bones, blood, shit, condoms, tampons and other such items associated with animal effluence, was to provoke in others a similar rupture of perspective that 4 Dias 4 Noites had triggered in the artist himself. Ultimately Barrio wanted the discovery of these horrific-looking things to shock certain elements of the public out of their complacency about the political status quo. “I never put the bloody bags in the poorer areas, the favelas, though,” Barrio points out. “They’re used to seeing violence and dead bodies, whether they’re killed by the drug dealers or the police. I would never have put them in places where violence happened. They must be in places in which such things are out of the regular order, to make people see things out of the regular order.” While politically dangerous – the police were frequently called to investigate the bundles – Barrio avoided censorship (or arrest) by observing the reactions from afar, though the artist is at pains to note that his observance and the documentation of the action is secondary to the action itself.

In May 1970 Barrio walked the streets of Rio for four days and four nights, not stopping for food or rest, and without any planned route or destination

Barrio explains that he has paid little attention to the aesthetic qualities of his work – he used waste materials for pragmatic reasons – “there was no cost, they were readily available and it meant I could work anywhere” – as well as for their innate material qualities: they deteriorate quickly, leaving little evidence. This suggests parallels to Arte Povera, but Barrio points out that while in Europe there was a choice as to whether to aestheticise the ‘poor’ materials, in Brazil, where industrialisation was developing slowly, it was more a necessity. “The paint that was made in Brazil was of very poor quality; it would not endure,” he says by way of example. “If you were a painter and you wanted your work to last, you had to spend money on imported paint.” Barrio’s interest in impermanence is not only influenced by his adopted country (he retains Portuguese citizenship) but also by the few childhood months he spent in Angola. The artist owns a large collection of traditional art from the country, part of which he inherited, but the rest of which are his own acquisitions. Gesticulating at the crowd of traditional masks that dominate his living room in Rio de Janeiro, Barrio says, “While great skill went into their making, these objects were not meant to last or endure; they were supposed to have a limited existence.”

How does the artist’s protest work – which often verged on anarchy – hold up now that its original target, the Brazilian dictatorship, has collapsed? How does the work made since the transition to democracy in 1985 react to an arguably far more slippery and wily enemy: neoliberalism? The artist continues to make his work from cheap materials – and his exhibitions deliberately avoid any objects that could become fetishised or easily subsumed by the market. His Brazilian Pavilion at the 2011 Venice Biennale consisted of what looked and smelt like piss up the wall, alongside a real box of fish heads, reeking in the Italian heat, and other similarly unattractive installations. The walls were covered in lines taken from the artist’s various artist books – which he refers to as CadernosLivros (‘notebooks’) – that he creates to accompany actions and performances. Installations for the São Paulo Bienal in 2010 and for Okwui Enwezor’s Documenta 11 (2002) had a similarly chaotic, degraded quality. Smaller works that might occasionally surface at art fairs have a violence to them: for example, …Situation…Town…y…Country… (1970) is a bundle of breadsticks resembling a collection of high explosives. Or they might include materials that could put off the average collector: the burnt, untreated cardboard, erratic scribbling on paper and unidentified brown mulch present in a series of framed wall-mounted bricolages made throughout the 1970s and recently revived, their collective title Os Meus Desenhos Heterodoxos (My Heterodox Drawings), is perhaps a sly fuck-you to the doctrine of capitalism. “My work has stayed the same, even though the world has changed around it,” Barrio says. “It is the system that changed, it has accepted the work into its institutions.” He goes on to reaffirm the mindset of anarchy from which his work is generated. “It’s not directly ‘political’. It exists outside that… it is about resistance. So if it is now about resisting the art market or the artworld, then fine.”

This article originally appeared in the September 2013 issue.