How does Firestone’s text read, three decades after it was first published, in a world where popular understanding of ‘mental health’ has fundamentally changed?

Shulamith Firestone’s Airless Spaces, the radical feminist writer’s collection of short stories, begins with a dream. A ship is sinking – a ‘luxury liner’, to be specific – and the narrator, fleeing the ‘hysterical’ forced gaiety of the wealthier passengers ‘dressed to the nines’ on the upper decks, is searching in its bowels for ‘something that would supply an air pocket’. She climbs into a refrigerator, hoping to be saved when rescue teams are dispatched to the submerged vessel. Upon waking from her dream, the narrator discovers that a real liner has actually sunk in the night, but, as the disaster happened in the Bermuda Triangle, ‘no attempt would be made’ to recover it.

Blackly humorous and seriously claustrophobic, this story – called simply ‘Frontispiece’ – is a tonal microcosm of the book itself. Firestone’s first (and only) work of fiction, initially published by Semiotext(e) in 1998, Airless Spaces is split into five parts: ‘HOSPITAL’, ‘POST-HOSPITAL’, ‘LOSERS’, ‘OBITS’ and ‘SUICIDES I HAVE KNOWN’. Apparently linked by their shared nameless narrator, each section follows its characters through the unforgiving landscape of psychiatric hospitals, cockroach-ridden New York housing and the various inadequate institutions tasked with providing some form of safety net for those who find themselves on society’s margins.

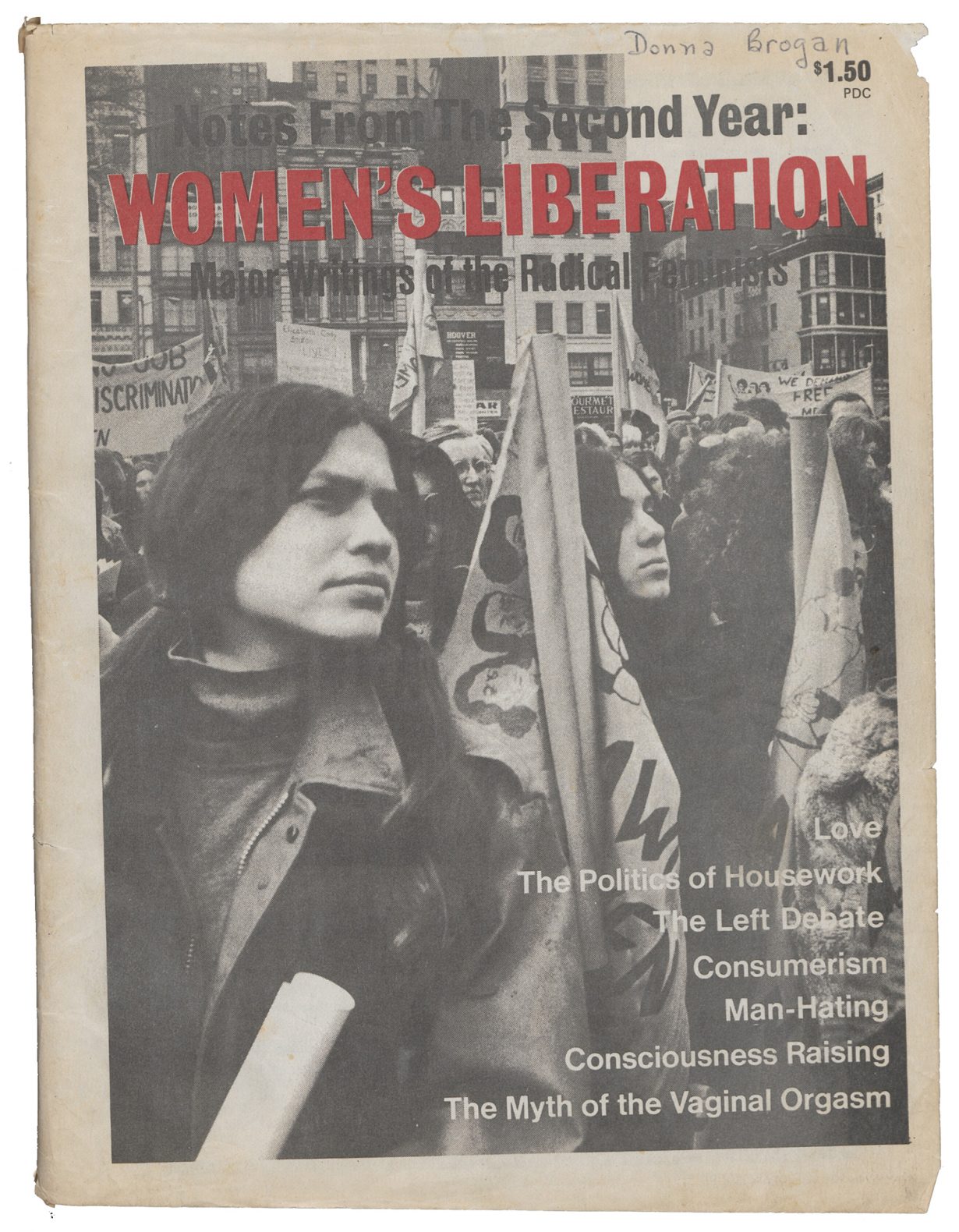

Firestone was drawing on her own experience. A lodestar of the 1970s radical feminist movement, her polemic The Dialectic of Sex (1970), which argues that reproduction is at the heart of patriarchal oppression and envisions the liberated future that developments like the artificial womb might bring, remains a controversial but essential touchstone of feminist theory. Yet she was badly burned from her experiences in the women’s movement, as Susan Faludi’s essay ‘Death of a Revolutionary’, first published in 2013 and collected in the ‘Reader’ that closes this new Silver Press edition of Airless Spaces, makes clear. After being ousted in 1969 from New York Radical Women, a group she had cofounded two years prior, which was also the first women’s liberation organisation in the city with a particular commitment to the second-wave practice of consciousness-raising, Firestone withdrew from organising and, increasingly, from social life; after a nervous breakdown, she was diagnosed with schizophrenia and spent the rest of her life in a cycle of hospitalisation and release. Her body was discovered in her apartment in 2012. In this context, the frontispiece to Airless Spaces reads almost prophetically. Yet Lourdes Cintron – who was part of a support group of younger feminists who cared for Firestone during the 1990s and were instrumental in getting the text to publication – warns against, in her contribution to the new edition, reading the story simply as an allegory of Firestone’s psychological ill health. It’s as much about those passengers on the upper decks ignoring the rising waters as it is about the narrator cramming herself into a refrigerator that might as well be a casket.

Airless Spaces is an exercise in paying attention. Elsewhere in the reader, Firestone’s sister Laya F. Seghi writes that when ‘My Sister Shulie’ was composing the stories, she ‘wanted her deadpan vignettes to be a window into a world most people would rather ignore’. To really look at these characters is to see how fragile the links are that connect ‘normal’ people to their lives. A repeated motif in the text is how rapidly a hospital stay alters your physical appearance: our narrator can no longer fit into her Levi’s; another character, after a forced shower and haircut, ‘began to look like a mental patient, not an attractive woman who just happened to be thrown into a mental hospital’. In ‘Passable, not Presentable’, the narrator describes ‘the ghastly difference’ her ‘lost looks’ make to the way people respond to her: ‘people turned away from her after one glance in the street’.

Although Airless Spaces may be, as cultural historian Hannah Proctor writes in her accompanying essay ‘Unaccustomed Tenderness’, a significant departure from the ‘grand scales, zooming velocities and sweeping temporalities’ of The Dialectic of Sex – in its ‘stifling atmospheres and small rooms’, time ‘barely passes’ – it shares the inquiry into power and its abuses, both individual and systemic, that characterises feminism as a project. Alongside the litany of institutional failure and neglect, Firestone also observes how social reproduction and hospitalisation interact: ‘Loving the Hospital’ tells the story of Mrs Brophy, whose voluntary stays are her only respite from the labour of ‘juggling the cares and worries of a large family’. Indeed, many of the tales are populated by women who, left by their husbands and ignored by their friends, find that after exhausting themselves caring for others, nobody is left to attend to them (in ‘The March Fracture’, the bones in the arch of a woman’s foot literally collapse under her weight during a trip to the supermarket).

This is also a book about what happens when movements fragment. The history of feminism is also a history of recrimination and loneliness, of wounds that won’t heal. As Airless Spaces progresses out of the hospital corridors, Firestone’s experiences become more legible in the text: by the time we reach the ‘OBITS’ and ‘SUICIDES’ sections, stories of the lonely deaths of Myrna Glickman and Valerie Solanas, who both orbited the same feminist circles as Firestone, gesture towards the dissolution of the fantasies of solidarity and sisterhood that characterised the movement at its most optimistic. Writing in the same year the book came out, Kate Millett – the author of Sexual Politics (1970) and a key figure in the movement herself – reminds her readers of the feminists ‘time forgot’, who ‘disappeared to struggle alone in makeshift oblivion or vanished into asylums and have yet to return to tell the tale’.

Airless Spaces resists consolation. In the three-decade interim between its publication and this reissue, the way ‘mental health’ is understood in the popular imagination has changed: bastardised self-care proliferates, compounded by the TikTok-ification of trauma, in which pathologisation and diagnosis are only a 60-second attachment-styles-video away. This does little, however, for those who, like Firestone’s characters, can’t ‘look passable’, who can no longer write or think or do anything at all. This is not to say that the book refuses to engage with the resurgence of traumatic experiences as a cause of psychic fracture. In the final story, which is the most identifiably biographical, Firestone theorises that the inconclusiveness of her investigations into her brother Danny’s sudden death ‘contributed to my own growing madness – which led to my hospitalization, medication and a shattering nervous breakdown’. But this is only one story of the many collected in this text. There is a radical equality of loneliness here: to lack consolation is not to lack power. In ‘My Sister Shulie’, Laya recalls that from her very earliest memories, Firestone was an astute observer of her environment. She perceived people and dynamics in a unique way. Her perspectives were often unwelcome at home or school, but she remained undeterred.

It’s difficult to describe Airless Spaces as a ‘welcome’ text, but it is a significant and necessary one. Its persistence in spite of hopelessness gives us something: an air pocket, after all.

Helen Charman is the author of Mother State: A Political History of Motherhood (2024)