Situated somewhere between obsession and disgust, attraction and revulsion, why slime became contemporary culture’s material du jour, from Fashion Week to Instagram

When I imagine my dream dinner party I can never decide the exact guestlist, but I’m certain Patricia Highsmith would be there. This is not because I expect the author of the Ripley novels (1955-1991) to be a charming conversationalist. Far from it. It’s because chances are the notoriously prickly Patricia would arrive with a handbag full of slime. The others around the table hardly matter, when, during a lull in proceedings, Highsmith might pull a snail or two from her purse, setting them loose amongst the hors d’oeuvres.

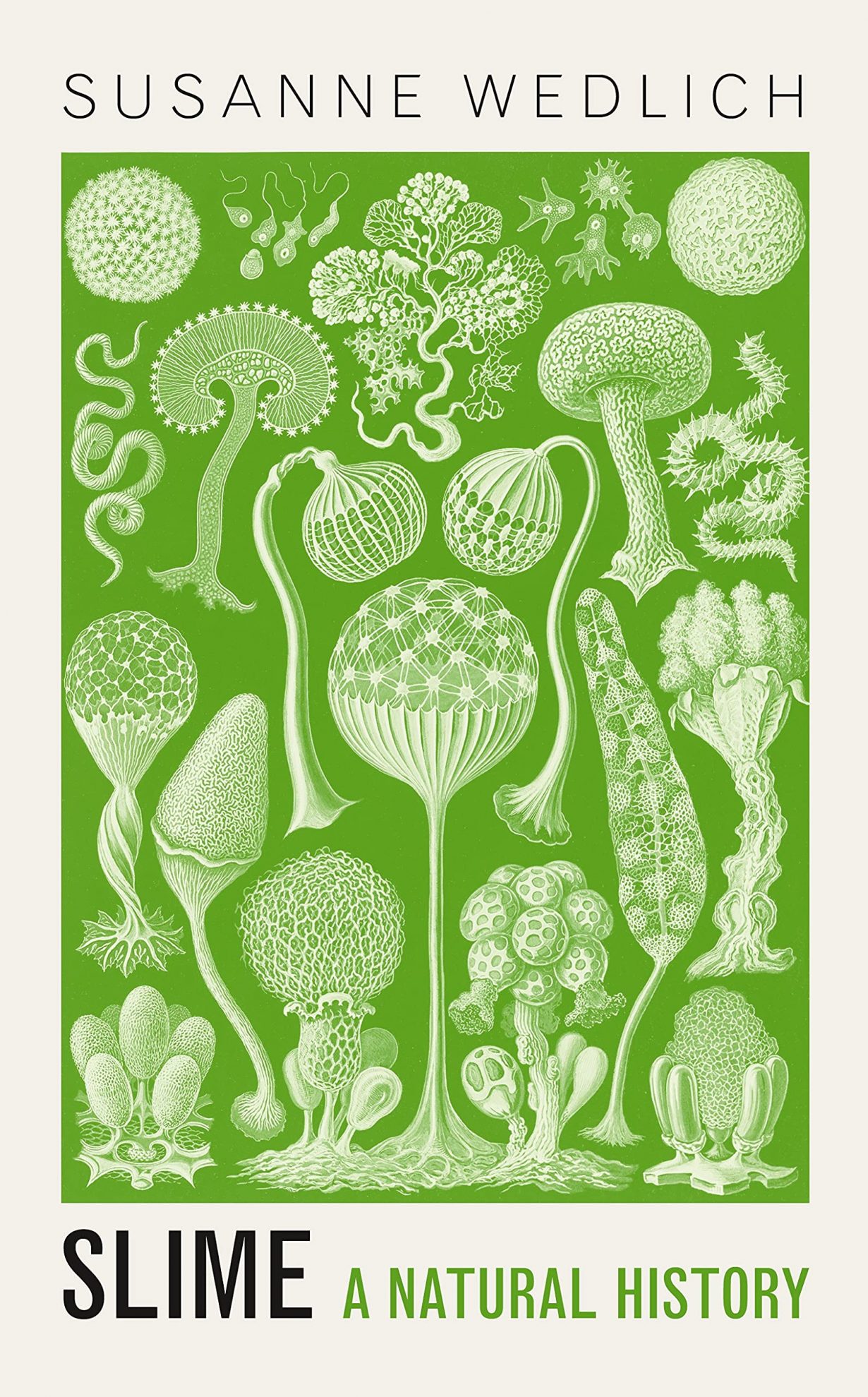

Highsmith was a shock artist; she had an instinct for provocation. But, as Susanne Wedlich suggests in her fascinating new book, Slime: A Natural History (2021), Highsmith’s love of snails went deeper than a desire to enliven dry dinners. If that was the case, why go to the trouble of smuggling batches of the gastropods across international borders by concealing them in her bra, their secretions oozing under her breasts?

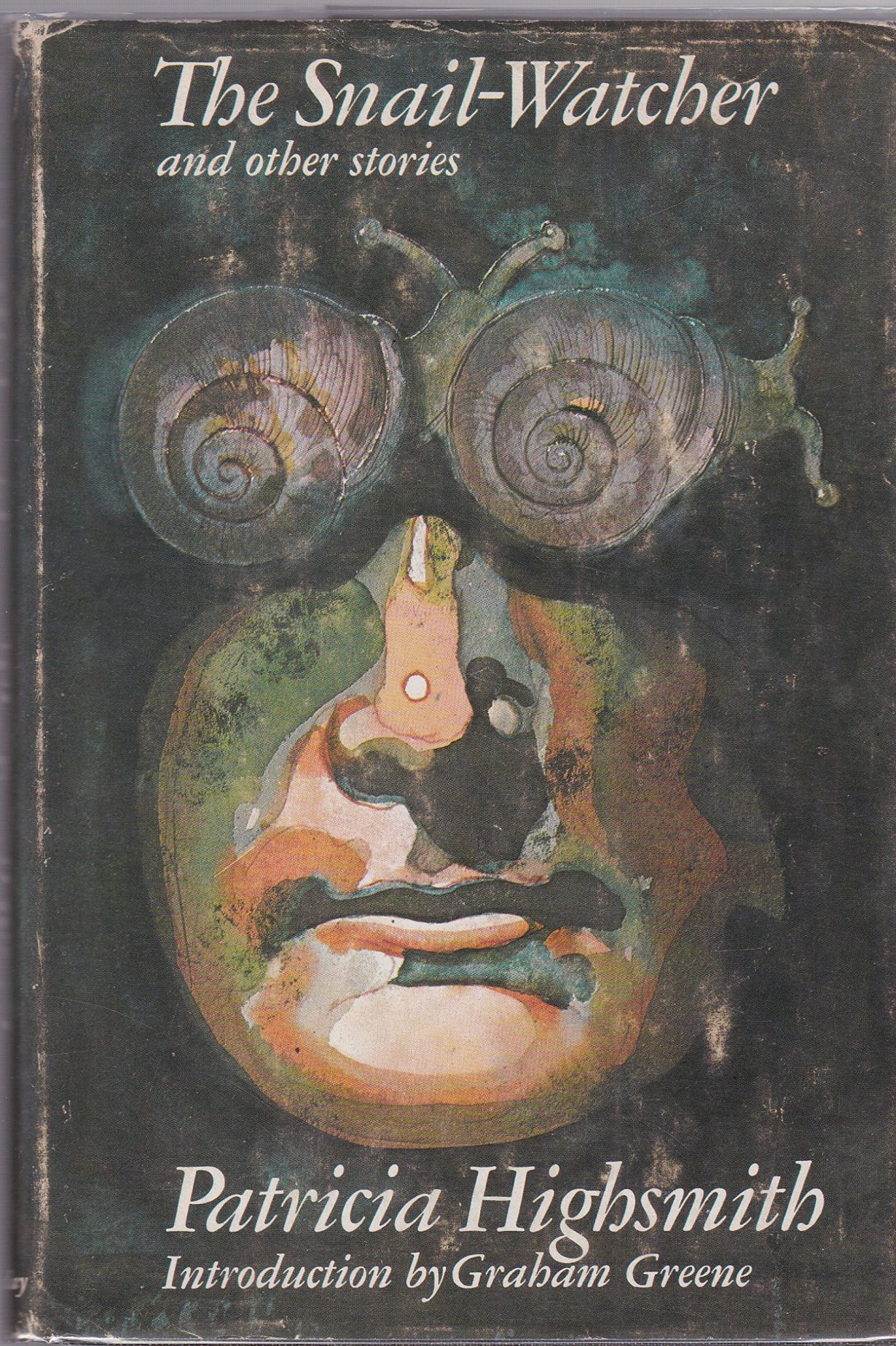

Wedlich suggests Highsmith’s subterfuge shows ‘a surprising degree of care, perhaps, for a woman with an abrasive personality’ – a care signalling an intrinsic appreciation for slime’s illicit appeal. Sometimes a snail is not just a snail. ‘There is’, Wedlich writes, ‘a long tradition of the snail as a symbol of transgressive feminine sexuality’ – something slippery that threatens to seep, gush and engulf. Certainly, while Highsmith said she found it ‘relaxing’ to watch the viscous hermaphrodites copulate, in several of her stories men are devoured by them, consumed by a ‘glutinous river’ (The Snail-Watcher, 1970), swallowed by slime.

Was it terror of just such a sticky end that lay behind French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre’s aversion to sea creatures? While Highsmith made snails her bosom buddies, Sartre was famously horror-struck by molluscs and shellfish. When, in an interview, Simone de Beauvoir asked which foods nauseated him, Sartre responded simply, ‘crustaceans, oysters, shellfish.’ Pressed to consider whether his disgust was connected with what he thought about mucus and viscosity, he agreed: ‘certainly’. And certainly, Sartre was preoccupied with slime – the substance he described as a ‘degenerated liquid’; ‘a soft yielding action, a moist and feminine sucking’; ‘like a leech sucking me’ (Being and Nothingness, 1943). How quickly the erotic slips into the neurotic. For Sartre, is the feminine like a leech? ‘This can’t and shouldn’t be more than speculation, but’, Wedlich speculates, ‘could slime have bridged the gap between [Sartre’s] deep-seated aversion to sea-life and sexual reserve?’ Some go further than speculate: Wedlich quotes Sarah Bakewell’s suggestion that Sartre ‘found sex a nightmarish process of struggling not to drown in slime and gloop’.

So, slime resides somewhere between Highsmith’s obsession and Sartre’s disgust; between attraction and revulsion; sex and death. This makes it truly an abject thing – not really a thing at all, but, as the philosopher Julia Kristeva describes it, that which ‘disturbs identity, system, order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules. The in-between, the ambiguous, the composite’ (Powers of Horror, 1980). Kristeva’s primary example is the corpse (both human and non-human, subject and object, decaying, of course, into slime), but she suggests other items that can elicit abjection: the open wound, shit, sewage, the skin that forms on the surface of warm milk. Fluid thresholds and unstable boundaries. All things gooey and taboo.

But, why be so concerned with slime? Why dwell on it? Well, because it’s everywhere. Slime belongs to the ocean bed and the roof of the mouth; it’s primordial and artificial; alien and deep in the guts. It accompanies disease, death, sex, and the start of life. It’s oil slicks, plastics, placenta, and ectoplasm. And, if you haven’t already noticed, it’s been seeping into the contemporary cultural scene for some time. It’s the material of the moment.

Wedlich’s book embarks on an eclectic and engrossing journey through the three-billion-year history of slime, connecting Highsmith’s snails and Sartre’s crabs to Ghostbusters (1984-2021), algal blooms, and the workings of the internal organs. But, when I think of slime, my mind rushes to Saturday morning telly. Being glued to the screen as grown-ups were plunged into litres of luminous gunge, or dumped in buckets of the stuff. As an early-90s millennial, I was raised on the gunge-filled British children’s TV gameshows Live and Kicking (1993-2001) and Get Your Own Back (1991-2004); I got to know slime as punisher and weapon, but also as illicit, anarchic thrill. Get Your Own Back. Swap the feminine for the childish (as many often do), and you have Sartre’s styling of slime as a ‘sickly sweet feminine revenge’ made manifest. Revenge served wet and slippery. Little did us ’90s babies know that we were entering the story at a late stage – at least a few decades on from slime’s cinematic peak. Referring to 1958’s The Blob and The Fly, Wedlich describes the mid-twentieth century as ‘a time when almost every film with a hint of spookiness was swimming in gunk’. Gunk: the perfect scare for the volatile Cold War era, when people legitimately felt under threat from radioactive sludge, fatal ooze. What could be better then, as a new century seeped into view, than to use the previous generation’s fears against them? The substance of their nuclear nightmares became a cause for celebration. The poles of revulsion and attraction shifted. Millennials absorbed the idea that gunge was something grown-ups feared – something nasty – but also, undeniably, something fun.

Slime has gone from being imagined as a threatening agent of chaos in the late twentieth century, to being embraced in the twenty-first. Consider the evidence. In 2017, Garage Magazine produced an ASMR-inspired film featuring Instagram star @craftyslimecreator, where hands decked in Chanel jewellery plunge perfectly manicured fingers into pots of slime. Two years later, Loewe launched its SS20 campaign with a shot by Steven Meisel: a blob of ‘green slime’ oozing between the fingers of another manicured hand (‘a play on symbols of popular protest’). The Zoe Report – a fashion site founded by infamous Hollywood stylist Rachel Zoe – pronounced slime green the ‘colour of the 2019 spring collections’, and ‘the trend that wouldn’t quit’ (the trend that engulfs). Not content with just the colour, at his spring 2019 show, Landlord creative director Ryohei Kawanishi sent models out with kaleidoscopic slime pouring down their faces. One topless catwalker was slathered with it all over his torso. Add to this already heady mix a sizeable dollop of Instagram’s #oddlysatisfying slime videos, slime influencers and entrepreneurs, and what emerges is a whole lifestyle industry gagging to drown in gloop. The fact that YouTuber Karina Garcia makes six figures a month through her ‘slime channel’ is perhaps less surprising when you remember Gwyneth Paltrow’s wellness and lifestyle brand is literally called Goop. Dollars are, after all, also slime green.

Can such a lucrative substance still be subversive? Can slime still cause a scene, like a snail trailing over a dinner set? Being hard to pin down is part of slime’s fluid allure. At the same time fashion fell for girlboss goop, fascists were getting milkshaked in the streets. Surely a few others saw the photos of Nigel Farage getting milkshaked and thought of Get Your Own Back? Alongside a persistent nostalgia for ’90s cultural products, the last twenty years have seen the emergence and increasing dominance of microbial and mushroom studies, burgeoning green movements, and a broad cultural fascination with fluidity, interconnectedness and the non-human. Perhaps this too can only be speculation, but could slime bridge the gap between these contemporary concerns?

The artworld is always poised somewhere between high fashion and the fungal underground, as artists attempt to make work that challenges the status quo, while the art market lubricates the global financial system. Yet, it is in this in-between space that slime’s potential as a positive disruptive force is being explored. Take, for example, the work of Jenna Sutela, Pauline Canavesio, Katya Bodrova, Nettle Grellier, Zhong Lin, Dom Sebastian, Craig Boagey, Maisie Cousins, and Honey Long and Prue Stent. Artists who, despite working across different mediums, create art that embraces the bodily, the messy, the gross, the gooey, and the fungal. These artists play with notions of taste and disgust, blending the digital and the organic to revel in futuristic surrealism and slippery in-betweenness. Their work is sensual and anarchic, beautiful and unsettling. They tackle mortality and animality, and all use the abject as a tool.

In a time when refugees are likened to ‘swarms’ by English politicians, borders are sites of violence, and bodies’ sexual characteristics are vigorously patrolled by the so-called ‘gender-critical’, surely there is a political imperative to create work that, in Kristeva’s words, ‘disturbs identity, system, order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules’. Indeed, Kristeva herself used the concept of the abject to analyse xenophobia and antisemitism, examining how particular groups of people are labelled as revolting figures, and how those individuals may revolt against their marginalization. By embracing the abject and revelling in the ‘revolting’, I would argue our slime-filled cultural moment attempts just such a revolution. At the end of her book Wedlich wonders whether, ‘instead of forcing our will on the rest of nature, perhaps we could try slime’s soft and slow approach for a change?’ Perhaps slime allows us to see the breakdown of boundaries as something that is not threatening, but liberating: no longer a source of terror, but radical joy.