A history of Southeast Asia, as told through 6,000 years of objects, succeeds in capturing a more diverse and complex story

On the face of it, you might think, as this reviewer did when it thumped through the ArtReview letterbox, that this book is just another in a series (previous volumes cover India and the Islamic World) that seeks to perpetuate an anthropocentric view of the world (via a focus on the products – and hence productivity – of humankind) and simultaneously boost the somewhat flagging cause of the ‘universal’ museum. The idea that museums – and 300-page books produced by them – can collapse time and space to bring everywhere and everywhen together in a manner that supports the fundamentals of globalism while masking the colonialism, looting and economic and sociopolitical inequalities that, in reality, sustain it. It’s much to her credit, then, that for the most part Alexandra Green, the British Museum’s Southeast Asia curator, does not do this.

Of course, almost all of the objects – which range from a cave painting to motorbikes and televisions – come from the British Museum collection (the cave painting did not). And many of them list donors (the likes of H. Ridley, Adelaide Lister and A.W. Franks) that make you wonder as to the exact circumstances of their provenance. After all, many of the items on show here arrived in Britain at around the same time (the second part of the nineteenth century) as naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace was busily blasting orangutans out of Borneo’s jungle canopy – and making locals climb up to fetch their shattered corpses – to fill the display cabinets of other British museums. But many of these issues are highlighted in the author’s breathless stampede through 6,000 years of Southeast Asian history.

First up, Green introduces the idea that, because of its diversity of language, cultures and religions, because of the mix of mainland and island communities, ‘Southeast Asia’ might not be such a useful cultural grouping as it is a geographical one. Second, if Europeans are introduced as traders and art collectors in the early parts of her accounts, they are certainly colonialists and extractivists by the end (and occasionally idiots too, as was the case with Charles Hose, a Cambridge dropout who occupied administrative positions under the White Rajahs of Sarawak, and whose large collection of ethnographic souvenirs from that place was acquired by the British Museum in the early twentieth century, and who tried to wean the indigenous peoples of that part of Borneo off headhunting by organising rowing competitions). Third, she concedes that there is a ‘difficulty in using objects to tell full histories’ of the region as a result of a tropical climate that renders many such objects ephemeral. Finally, at a time when historians such as Sunil Amrith are reimagining South and Southeast histories as being shaped by the forces of nature (more particularly water in his case) rather than culture and politics alone, Green takes time out (in the form of a thirteenth-century ritual water vessel – ‘exact ritual purpose unknown’ – from Java) to acknowledge that too.

What Green manages to do as a result is capture something of the diverse and complex group of histories and cultures that have formed what we call Southeast Asia today – from the influence of trade routes that spanned Persia to China in the first century BCE, to waves of religious influence encompassing Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam and Christianity. And of course the ability of the peoples in the region to accommodate and assimilate all of this – via multiple forms of storytelling, ranging from carving and weaving to architecture and performance art – into a series of unique and fascinatingly diverse cultural forms. If ever you need a quick guide to Southeast Asia’s history, this is it.

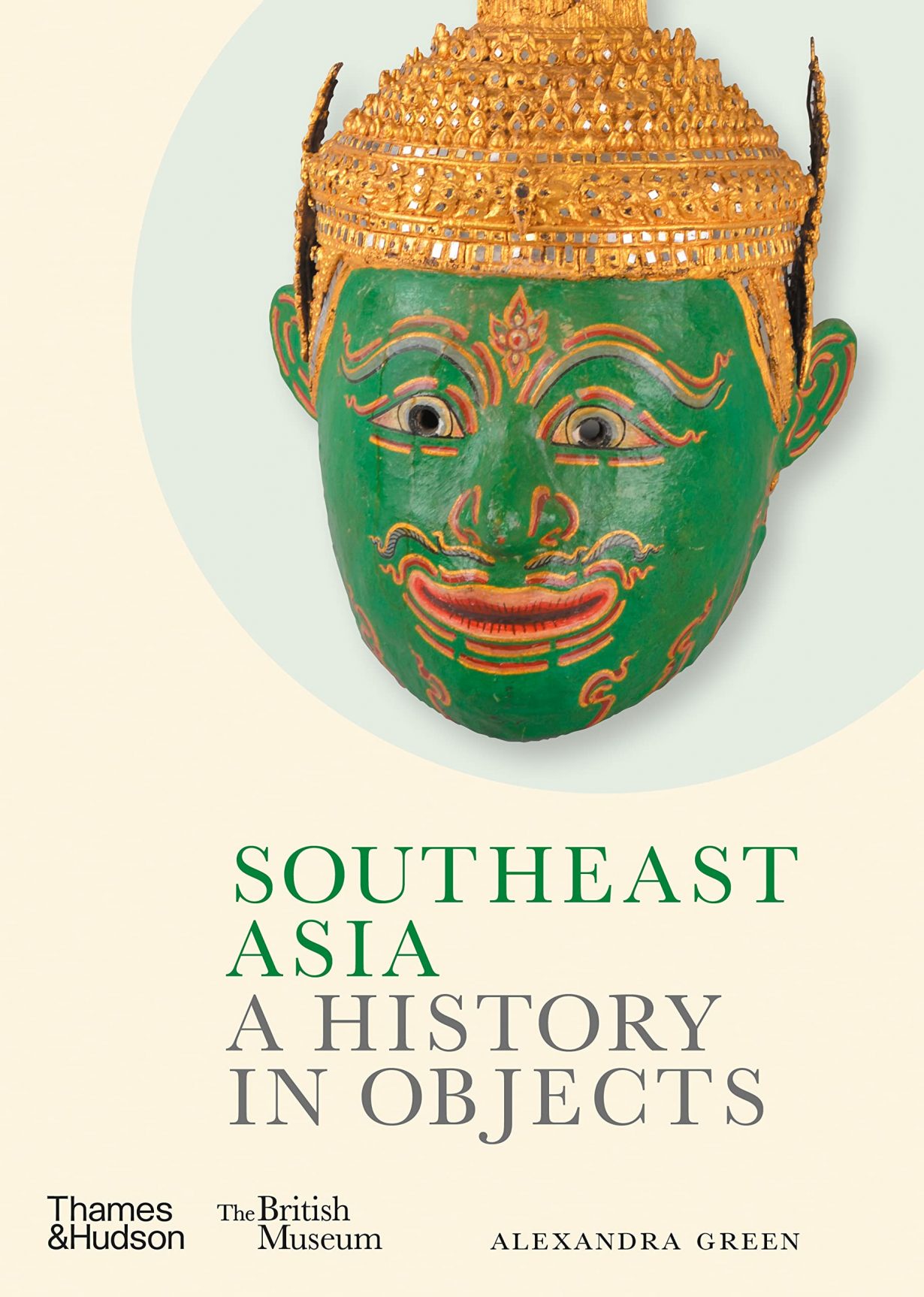

Southeast Asia: A history in objects by Alexandra Green. Thames & Hudson / British Museum, £32 (hardcover)