Before Musk and Thiel, a shadow history throws the often idealistic hopes of progressive science-fiction cultures into stark and unstable relief

Common wisdom has it that science fiction can’t necessarily predict the future, but that it can certainly work to defamiliarise the present. There’s an almost cosy reassurance to this idea, one that risks reducing the genre’s interpretative potency to a self-congratulatory fable. What’s more, it seems increasingly discordant with science fiction’s uneasy proximity to real-world technopolitical weirdness. A world that’s seen Grok – a chatbot developed by xAI and named after a phrase coined by veteran science-fiction novelist Robert Heinlein – spout antisemitic tirades and praise Adolf Hitler. Or encountered Peter Thiel’s data analytics company Palantir derive its name from a scrying stone in JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings (1954). Or witnessed Elon Musk don a T-shirt for the alien-eradicating survival-horror video game Dead Space (2013–23) while live-streaming on ‘migrant issues’ from the US–Mexican border.

Much stranger than prediction or allegory, the cultures of science fiction are increasingly interwoven with a technofascist milieu in ways that appear to exceed superficial inspiration or trollish dogwhistle. Instead, they furnish an absurd and programmatic literalism in which the genre’s allusive capacities for caution and speculation have been rewired as blueprints and schematics by reactionary world builders. How, then, do we discuss the uses of science fiction at a moment when the genre’s ideas and imagery are captured by biohackers, accelerationists, effective altruists and AI evangelists?

In his recent book Fluid Futures (2024), the theorist Steven Shaviro observes that science fiction ‘moves towards both utopia and dystopia’ in imagining how things might be different from real-world circumstances, highlighting the genre’s particular knack for thinking through contingency via techniques of speculation, extrapolation and fabulation. But it’s a strange state of affairs when a common dystopia might be monopolised and pressed into service as a utopian business plan by a wealthy individual, as recently seemed to be the case when the conservative columnist Ross Douthat was left aghast while grilling Thiel on his transhumanist beliefs for The New York Times. Asked whether or not the human race ‘should endure’, Thiel couldn’t muster an answer that didn’t leave him looking like a cyborgian antichrist with his thumb placed firmly on the species’ kill switch.

Thankfully, there’s a recent spate of popular but rigorous scholarship that tracks the sci-fi beliefs of the reactionary right with equal parts sniping humour and pragmatic urgency, from Gil Duran’s web resource The Nerd Reich to comedian Kate Willett and academic Emile P. Torres’s rousing podcast Dystopia Now. My attention has been particularly drawn to the work of Jordan S. Carroll, whose book Speculative Whiteness: Science Fiction And The Alt-Right (2025) documents the insidious recuperation of science fiction by racists and conspiracy nuts. In his telling, he cites myths of white interstellar heroism and the threat of a ‘great replacement’ in which white people are supposedly facing extinction through interracial relationships. It makes for harrowing but necessary reading, and its contributions to the field have recently been recognised with a prestigious Hugo award for Best Related Work in an award process that has historically honoured writers as challenging and diverse as Charlie Jane Anders, Philip K. Dick, Cixin Liu, Tamysn Muir, Dan Simmons and Emily Tesh.

Speculative Whiteness illuminates a shadow history that throws the often idealistic hopes of progressive science-fiction cultures into stark and unstable relief. Since Ursula K. Le Guin suggested that science fiction’s fundamental role was to imagine alternatives to capitalism, progressively inclined writers and artists, myself included, have strip-mined the late author’s 1986 essay ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’ ad nauseam (often pairing it with the writings of Octavia Butler) in search of conceptual resources that offer empathic and ecologically sustainable toolsets for artmaking and community formation in a world of accelerated capital: racialised, carceral and terminally extractive. Carroll’s book tells a startling counternarrative of what the right was up to while these admittedly noble efforts were underway. And while the alt-right no longer exists in the form that buoyed Donald Trump’s first ascension to power – a turning point that Carroll locates in the Charlottesville demonstrations of 2017, beyond which it morphs into various shades of MAGA fanaticism, Q-inflected conspirituality or poisonous tributaries of the manosphere – its ideological legacy can be traced in the tangle of beliefs that constitute the tech solutionism that seems to define the present moment, from the exclusivity of transhuman enhancement to the apartheid imaginaries of intergalactic migration.

For Carroll, the intimacy between extreme rightwing politics in the US and Europe and science fiction isn’t a contemporary phenomenon, but one that has deep roots throughout the twentieth century. The first significant neo-Nazi party in the United States was led by a science-fiction fan, James Madole, who had used the genre’s fanbase as a recruiting ground prior to leading the National Renaissance Party in 1949. Madole’s ideas were influenced by a racism that delimited the future as the preserve of white folks, suggesting that it was only when the gene pool had been ‘purified’ that the white race could fulfil its true destiny in the furthest reaches of space. Carroll perceives this myth recurring throughout science-fiction fandom, ‘whose members often saw themselves as the earliest ancestors of a new hyper-intelligent species destined for space’.

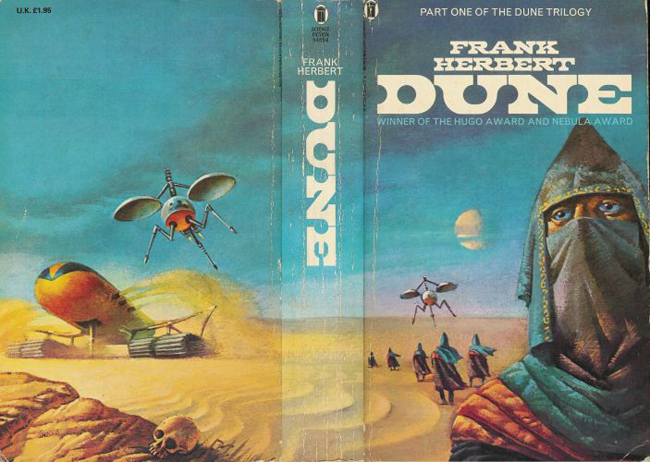

As such, Carroll identifies its influence on the geeky accelerationism of Dark Enlightenment philosopher Nick Land, who sees ‘autistic nerds’ as the destroyers of the idiotic masses, inducing an antidemocratic, Terminator-like singularity from the future. He also sees it in the surprising turn to science-fiction criticism of neo-Nazi activist, antisemitic conspiracy theorist and punchbag Richard Spencer, who reconfigures the deep space travel thematics of Frank Herbert’s 1965 novel Dune into a racial myth of whiteness’s supposedly innate ‘low time preference’ (the ability to defer instant gratification in the hope of future reward). For Spencer, such ambitions are evidence of a Faustian trajectory of whiteness that replaces what he terms ‘Star Trek liberalism’ with an ‘updated feudalism’. Carroll astutely observes that while most people think of the far-right as promising ‘stability and permanence’, Spencer’s intention ‘is to convince European civilisation to recover this “desire for exploration, for risk-taking, for shooting the stars”’. It’s not farfetched (even if his ideas are) to see Spencer’s cosmic delusions echoed in the sieg heil-ing Musk, beneficiary of over $38 billion in government ‘aid, funding and orders’ for his companies (including SpaceX and Tesla).

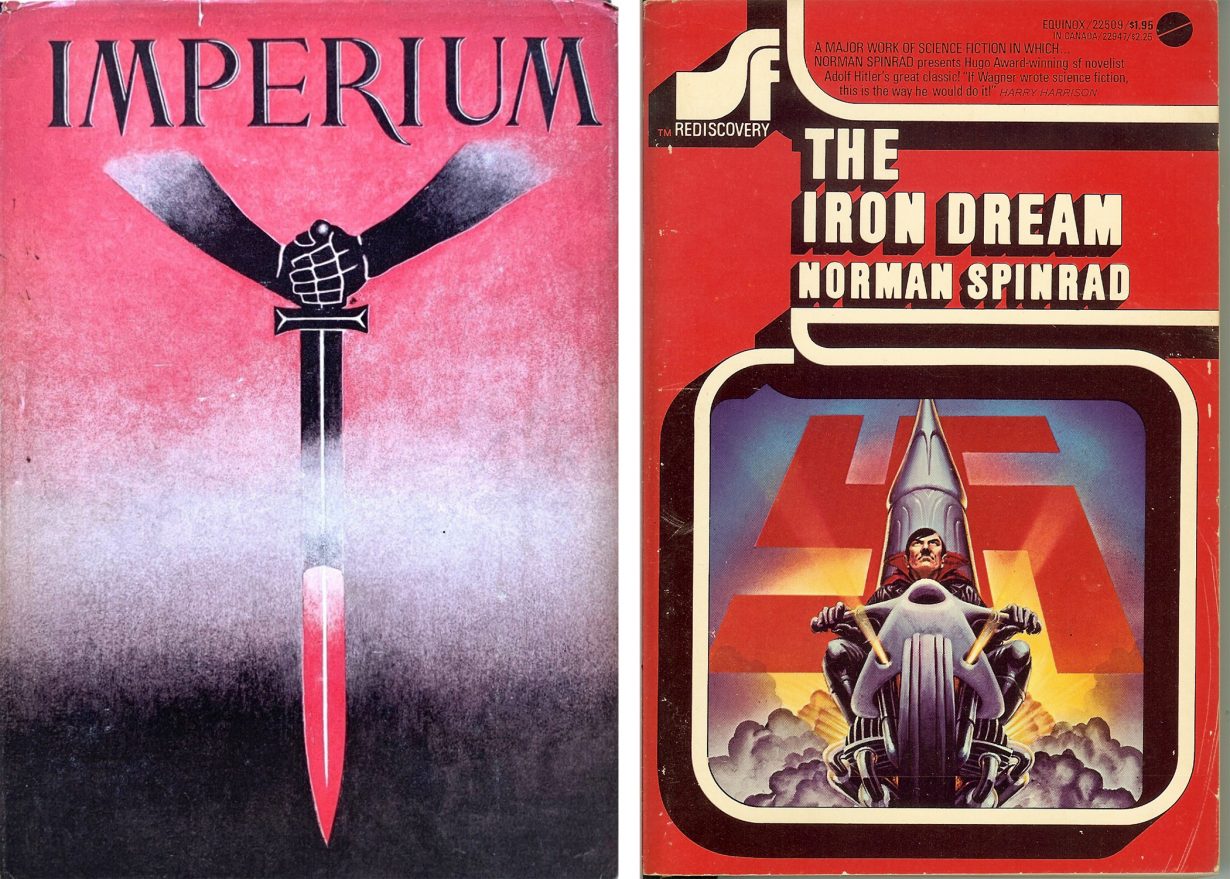

Through cases such as these, Speculative Whiteness identifies a common tendency on the right to glorify the power fantasies in cautionary tales like Alan Moore’s Watchmen (1987) or Herbert’s Dune series. It’s evidence of what Carroll dubs an ‘irony bypass’, perhaps no better illustrated than Musk’s widely mocked post on X back in November 2024 of a shot from Paul Verhoeven’s anti-fascist science-fiction movie Starship Troopers (1997). In uniform reminiscent of midcentury Italian Fascists, one character touches the body of an alien adversary and utters, “It’s afraid”. Musk’s interpretation labelled the alien as a ‘Big Government Machine’, the target of his own now failed firebrand war to erode governmental institutions. Verhoeven, of course, widely publicised his intention to ‘make a movie so painfully obvious in its satire that everyone who understands it lives in perpetual psychological torment inflicted on them by all the people who don’t’. For Carroll, such tendencies betray a metapolitical strategy that perhaps exceeds their apparent stupidity. While the contemporary right’s flirtation with science fiction might build upon a history of racist speculative novels such as Francis Parker Yockey’s Imperium (1948) and William Luther Pierce’s The Turner Diaries (1978), it retools the thematics and aesthetics of the genre for broader appeal in a postironic age. What’s more, perhaps readers like Thiel and Musk can simply afford to ignore the intended nuances of the genre, turning its contents into tools for their own forms of memetic warfare.

right 1977 edition of Norman Spinrad’s satirical work of speculative fiction The Iron Dream, 1972

That Speculative Whiteness has been awarded a Hugo is its own source of interest. Since their inception in 1955 in honour of legendary editor Hugo Gernsback, the Hugos have been a battleground not only for various and contrasting flavours of science fiction – from the stylistically traditional to the politically progressive – but for a culture-wars manoeuvring that has seeped into the popular imagination. In recent years the reactionary group the Rabid Puppies, led by alt-right science-fiction author Vox Day, have attempted to flood nomination slates via strategic voting with conservative and anti-diversity texts in an attempt to undermine the successes of nonbinary authors of colour such as N.K. Jemisin. The awards, meanwhile, have also been used to retrospectively honour the work of persecuted trans authors like Isabel Fall, author of a potent story about weaponised genders titled ‘I Sexually Identify as an Attack Helicopter’ (2020), which repurposed a notorious anti-trans meme as a provocation for one of the most affecting short fictions of recent years.

This year, Speculative Whiteness sat alongside nominations for anti-imperial works by novelists Ann Leckie and Adrian Tchaikovsky that develop languages of radical difference and inclusivity. In Tchaikovsky’s Alien Clay (2024), for example, an extraterrestrial planet rich in parasitic biota defies a fascist authority’s crude typologies, its endless mutations and evolutions appearing as ‘Bosch chimera until the very concept of taxonomy becomes inadequate to the task’. It’s an ultimately hopeful prospect, so at odds with the exclusive categorisations and racial hierarchies documented in Carroll’s analysis of rightwing imaginaries. Nonetheless, Speculative Whiteness offers its own cautionary fable of sorts, one that sits alongside tales such as Tchaikovsky’s and Leckie’s, illustrating the hateful utility that certain folks might make of science fiction’s speculative possibilities, where the genre’s capacity for a poetics of fabulation are reduced to vulgar solutionist schemas and delusional racist plots. The book’s recognition reminds those who perceive in the genre any hope for envisioning a way forward through present crises, to pay more attention to where its ideas and influences land across a much broader political universe than the localised galaxies of progressive fandom.

Jamie Sutcliffe is a writer, curator and codirector of Strange Attractor Press