A pioneering voice in Afrofuturism speaks to his mentee and now-curator about tradition, contorted systems and paying homage

This month, Bahamian-born conceptual artist Tavares Strachan curates the first solo exhibition in the United States by his mentor Stan Burnside, one of the most revered practitioners in the Bahamian art scene and a pioneering voice in Afrofuturism. Burnside’s reputation evolved from his work in Junkanoo, the carnival-style street parade and sacred cultural rite that takes place across the Caribbean – generally on Boxing Day – and that originates in West African religious practices. Burnside was the principal artistic director of the Junkanoo groups Saxon Superstars and One Family. Alongside that, Burnside has pursued an individual practice as a painter. Having studied for an MFA at the University of Pennsylvania during the late 1960s, he returned to Nassau in The Bahamas in 1979, where he decided that the multidisciplinary, collective nature of Junkanoo ‘was it’, a practice he shared with the students he taught at what was then the College of The Bahamas through to 1990, when he began to focus more on disseminating his message through his own practice.

ArtReview Tavares, when did you first encounter Stan’s work?

Tavares Strachan I think that it was on a studio visit with a class at the University of Bahamas when I was seventeen. I was blown away by it. I was already a huge fan of Junkanoo and Stan was basically a mythical entity in that community. I started seeing his painting as I got into more formal art myself. But I think Junkanoo was more egalitarian. Stan, you were having a studio practice at the same time, right – doing the Junkanoo stuff and then making individual paintings?

Stan Burnside Yes. I found that Junkanoo just created incredible energy to take back in the studio after Junkanoo season. It was working on a much larger scale than in my studio, and spending a whole lot more energy to produce works, so I would take that into my studio and just explode.

The visit Tavares was talking about was to an exhibition I was hosting at my home. The students were all asking just those simple questions, but there was this one voice that was somewhere behind the majority of the students that kept asking me very penetrating questions. And when I would answer, he would follow up with another question. Eventually, it became just the two of us in the room because he was asking questions on a different level completely than the other students. But from the very beginning it was very obvious that he had a very curious mind and a very active mind. In fact, he wore me out.

AR Can either of you remember what those penetrating questions were?

SB Well, I think one of them was how the Junkanoo influenced the work I was doing in the studio. None of the other students were on a level where they experienced the whole process of creating festival arts but he understood it and so he was curious about it. And he talked about the fact that the majority of my work has to do with empowering Black people. Very, very intelligent questions way beyond his years. It was very engaging.

AR What was it, Tavares, specifically about Stan’s work that attracted you to it?

TS I think at the time I was very curious about the hierarchies set up between ‘East’ and ‘West’. Specifically, when you are from an Afro Caribbean community, there’s this idea that Western value systems were more important than the ones that we were growing up with, and specifically with regard to the art form of Junkanoo versus the art forms of traditional painting or traditional sculptors in the Western canon. Here was this guy who was actually solving that problem. He was involved in Junkanoo at a high level, he was also involved in the painting thing at a high level. He opened up this possibility that you could do both.

This hierarchy didn’t really matter except again, when you think about how works were being discussed, how works are canonised, now they’re talked about in a public, or in a more international realm, there’s this limitation put on indigenous ways of thinking, making, being. I think a lot of my questions even then were about things like, ‘Is there a voice for me?’ and Stan was answering that question quite emphatically.

AR Given that we are talking Junkanoo, does that involve a collective practice or collaborative practice?

TS If you think of almost any West African traditional events – and I say West African because this is where most of the Bahamians descend from – they’re all an amalgamation of poetry, colour-production, mass making food, sound. It’s only when you leave and you go to the West, where there are these traditional segregations of painting, sculpture, etc, that these things are split. Junkanoo is a good example of when all these things smash together, when you have everything happening at once. I think the challenge for the West is that Junkanoo basically contorts the language system because you can’t describe it. If you ask anyone to describe what Junkanoo is, you’re going to get like 100 different definitions of it. But that’s what’s beautiful about it.

AR So, how would you define it, Stan?

SB Well, I think I remember when Louis Armstrong was asked ‘What is jazz?’ by a very well-known New York critic. He said something along the lines of, ‘Well, if you have to ask what it is, you would never understand even if I explained it to you’. I guess that’s what Tavares is saying. The whole collaborative approach to art is something that in Junkanoo really tells it all, and it ties us, it binds us to our African heritage where works of art are created almost as community events rather than as works for the individual artists.

AR How does that work alongside of more conventional Western studio practice for both of you?

TS I think my entire career has been un-learning what I’ve learned in these Western institutions. I’m trying to get back to that other way of thinking and making and being. I learned all this stuff. I learned that it was bad. I learned that it was not valuable. Now, I’m having to get back to my roots and to learn that all these ways of thinking and being and making are more valuable. I think my whole process has been about just basically unpacking and getting back to all the things I learned when I was fifteen.

SB For me, I think when I was in graduate school and I had artists like Alex Katz come in and sit down with me, spend a whole day talking about my work, I realised that we had a lot more in common than our differences. I found that even though there are many roles leading to great art, the sensibilities of the individual artist are pretty similar. Alex Katz, is for me, a brilliant technician. I went into the studio and he showed me his whole process. It’s very formulaic, but it’s very definite. It’s fast, it’s energetic, a lot like Junkanoo. The spirit in Alex Katz is very physical and very clear, quick decisions. It makes you realise that even though we are very unique in what we’ve created in the Bahamas collaborative approach, that’s only one community of artists and there is a global community of artists.

I think the brilliance of Tavares, even more so than me – I’m pretty provincial and regimented – is that he has this ability to cross cultural lines and communicate with all of these different languages.

AR Is there a sense, then, Tavares that your putting on the exhibition of Stan’s work in New York is an act of translation in itself?

TS In the West, we have this way of thinking about value in numbers: like volume equals good. What happens to a language that only 250,000 people speak, which is the language of Junkanoo, and what happens when that language goes to the global scale? What happens when it goes onto that stage?

To see Stan’s work on a global scale I think challenges the notion that you need 100 million people to be able to speak the language for it to be valuable. What’s the value of language, and what’s the value of a language that only a few people speak? Is there any value? That’s not to say that Stan’s work is only for people like me. I think the question is the question of jazz, it’s a question of reggae, it’s a question of how do we engage with these forms on a global scale?

AR How do you then take the context with the work? I think gallery spaces have a tendency to strip context out of things.

TS This work is about humanity, human experience. When you say humanity and human experience, I think you have to contest that with the idea that, for a lot of us, we weren’t seen as people 150 years ago. When you say human experience and humanity, I think it has to sit within that context, that framework.

SB To add to what Tavares is saying, I never think of myself as speaking to a limited audience. In fact, to a great extent – I know it might sound egotistical – I think of myself as painting for history. I think that eventually, if my work lasts, people will find something truthful in how I have viewed the world. I’m not really interested in my market here in the Bahamas, or the market in the USA or in the UK. I’m really painting because I see certain things and I want to represent them.

The one thing that I am dealing with right now, is the idea of our people. When I say our people, people of African ancestry, and our place in the world in 2022. I’ll be seventy-five years old my next birthday. When I look back on my life, I don’t see the community of Africa as being any nearer to self-determination than it was when I was born. To me, nobody is speaking on that. This body of work really speaks to that. It’s an expression of the outrage that I feel. Then I have to accept that truth.

TS I think it’s interesting to look at Stan’s generation and my generation (and obviously, there’s two generations after), to think about how the status quo functions in the context of these generational dialogues about personhood.

To me, this is the idea that many, many, many, many years ago, depending on where you were from, you weren’t allowed to be called artists based on the Western canon. I think, obviously, that’s in the middle of being significantly changed. I think the framework of the West’s desire to hyperlabel you as a specific kind of maker or creative comes with a certain problematic edge, because it could be realised as another kind of colonialism: ‘Oh, by the way, I get to push you out and I get to welcome you back to the debate. To take credit for it all.’

AR As if it’s an external decision to say, ‘Now, you’re useful again’. But I think this goes back to what Stan was saying about writing your own narrative and your own history.

SB I was there long before Black Lives Matter. I was there in James Baldwin’s time. I think a lot of the world is opening their eyes now – the so-called ‘woke’ spirit that just enveloped the world. I was there a long time ago. The burden of seeing things, seeing that so clearly, and not to be able to get others to even take notice of the plight of our people is extraordinary. It’s just a human phenomenon.

AR Now that you’re seeing what you were trying to talk about years ago becoming relatively mainstream in terms of discourse, is that frustrating because of all the time no one was listening?

SB Not really. To me, the most important thing is that we can come and accept certain truths about how the world has been split up. If we agree that all men are created equal, then we’re a long way from really showing that. I don’t care who gets credit for it. I think if the world could move in a direction for equity and equality and all of that, I’m all for that.

AR Can you talk a little bit about the works you’ve selected for the exhibition? Some clearly have elements of religion in them but then there is also quite a broad-ranging series of decorative motifs and styles.

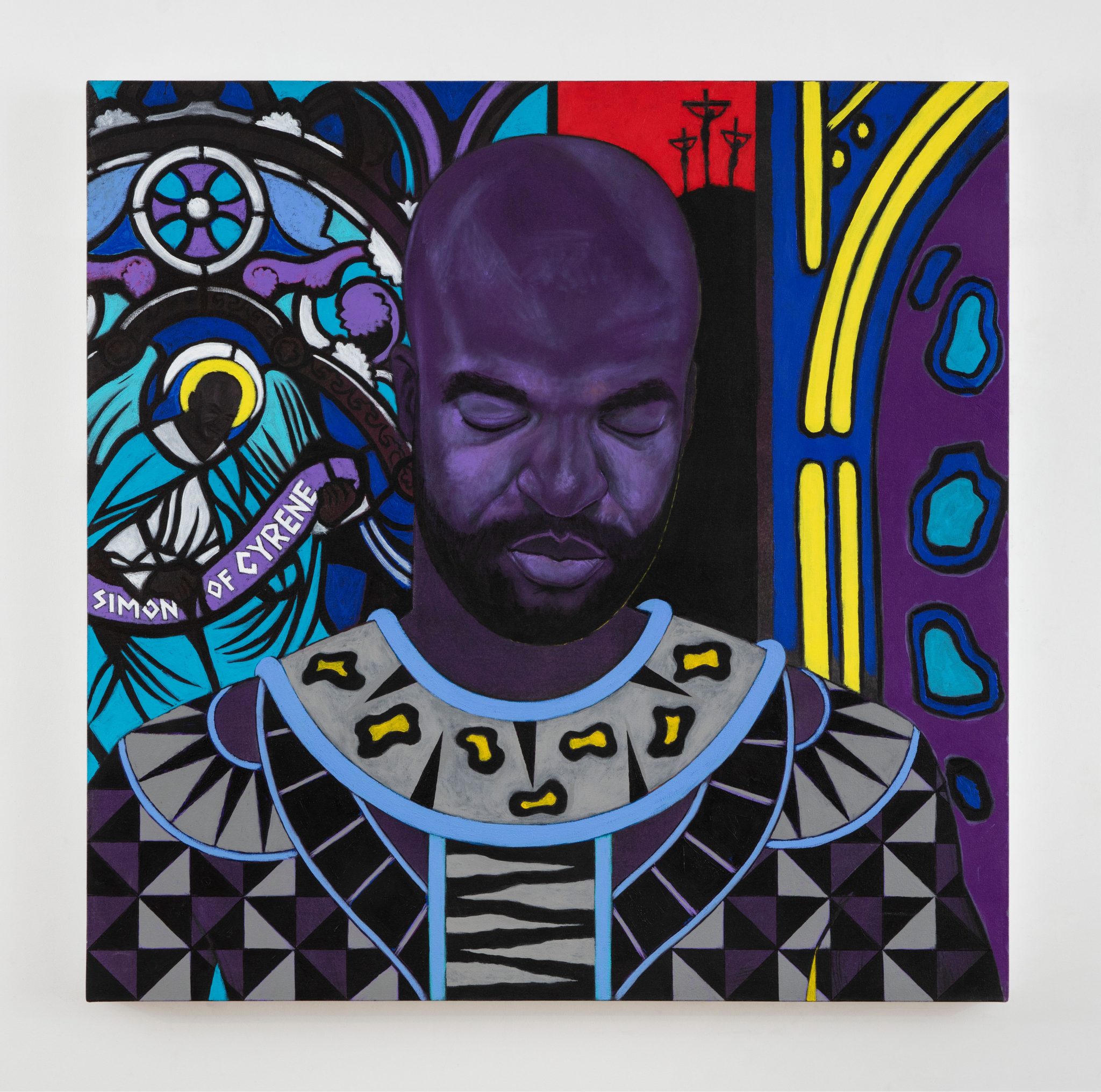

SB Simon’s Torment (2022) is all about Simon of Cyrene. When I painted it, I was thinking of the story told about how Simon of Cyrene was forced to help Jesus carry the cross. Knowing history and the way people of our hue are treated, if Simon of Cyrene sacrificed himself and went and volunteered his services to help Jesus carry the cross, that would be too heroic for a Black man. But I wanted to picture him. I wanted to see him as a hero that is not pictured as a hero. A Black man who sacrificed himself to help Jesus with the cross.

I thought it was a moment that showed the humanity of Simon. After Jesus was put on the cross, he went into his prayer room and was just in torment for the experience that he had. It has to do with as much the experience of Jesus carrying the cross as it has to do with the way Black people are treated and the way they are written about in history.

AR Do you see that as one of the works of reclaiming those narratives?

SB I think so. I think we have to be almost Disney-esque about writing our history. The facts that you know sometimes that are written down by others are not necessarily the true story. To a great extent, my father and Tavares’s father, and the older Bahamians, they have this habit of talking about historical figures, and of course, they’ve just created it in their own minds but it’s based on their experience of humanity.

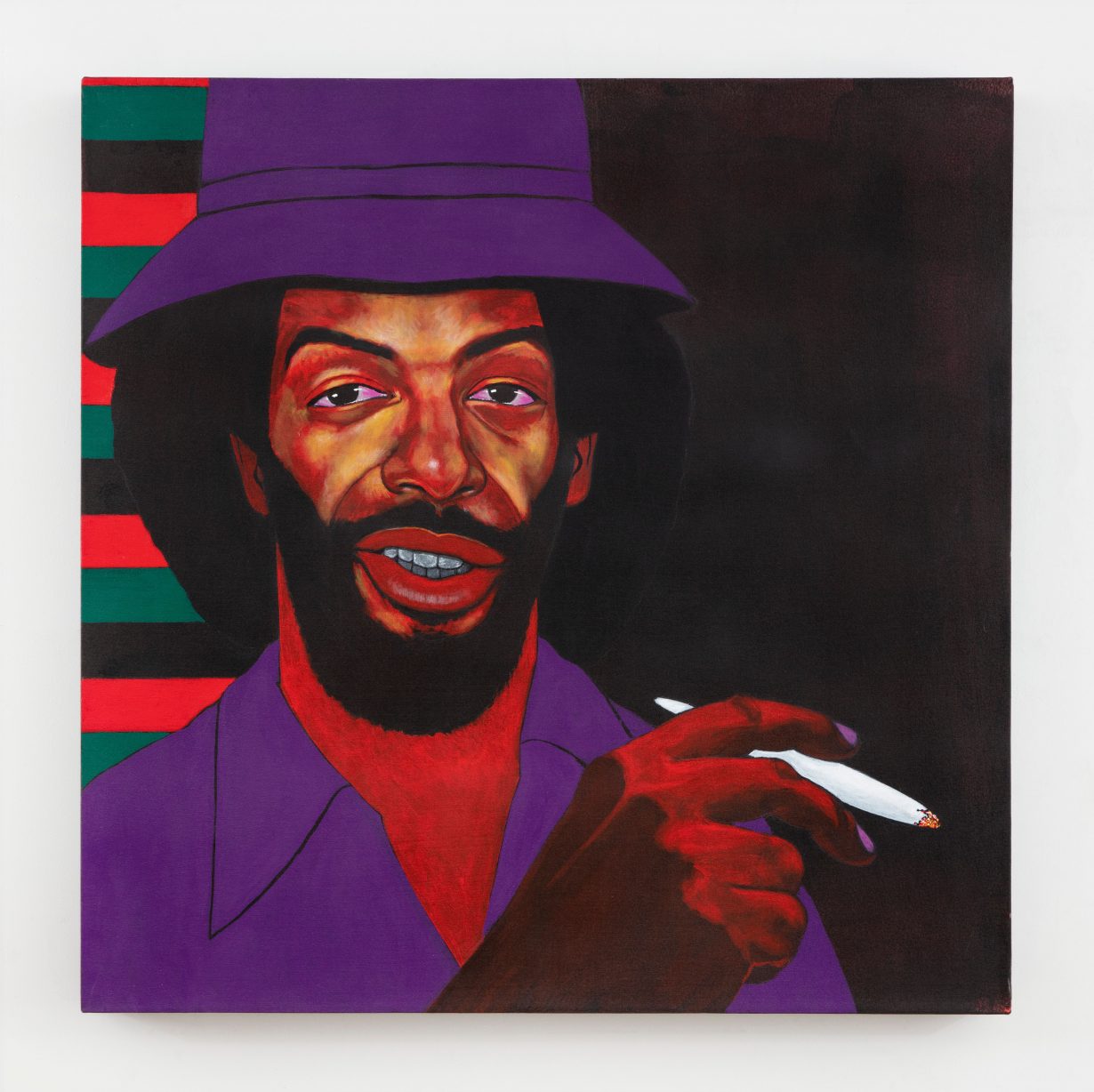

Badass MF (2022) could be anybody. Badass MF could be Bruce Springsteen. In particular, this painting is depicting the spirit of a young man born into a world where he is given certain hurdles that others aren’t given, and his ability to stand up and have the self-confidence to stare the world directly in the face without fear and to survive. To a great extent, Black people have to be badass motherfuckers in order to survive. There’s no way with the conditions and the circumstances that we’ve had to deal with that we could survive those just being normal individuals.

AR It seems like you’re talking about two things: one is the idea of individual personhood – the act of being acknowledged as a person, a human being; the other is this more general acceptance of human dignity that seems to come through the paintings.

SB I labour with that. I think so many things tell us exactly how people feel in the world. When we say ‘people’ in that sense I mean the powers that they feel in the world. The fact that Africans and to some extent non-white peoples never sit at the table when it comes to deciding what happens with the globe. Questions about the survival of the human species. You hardly ever see African communities sitting at those tables. That is something that I struggle with and that I have a lot of anguish about. The reality of that is what causes me to strike out in my work in a way that just acknowledges that I see that.

That thinking allowed me to do a body of work called Whispers and Screams and it was all about paying homage to those hundreds of thousands of people who were lost in the Middle Passage. One of the most moving experiences I’ve had was going to a Holocaust museum and seeing how the Jews never forgot those people who perished. I just feel the same way about our people and I don’t want to pretend like it was just a slave trade that happened years ago.

No, those were human beings and we need to call out their names and acknowledge what happened to them. It really has to do with that love and that empathy and that solidarity I feel with my people who’ve been through hell and who I love and who I think are as beautiful as any others in the world. I truly believe that all human beings are equal and all human beings are beautiful. I don’t judge anybody on the basis of colour or religion or sexual preference or anything like that. I believe we are all one family. That’s the name of our Junkanoo group, One Family.

TS I think, as people of colour, sometimes we get caught in the web of having to carry the burden of sadness. I also see a lot of joy in the work. Can you talk a little bit about that?

SB Joy is something that I feel in being alive and being able to face the world. I think the festival arts that we do helps us to feel that sense of joy, because there’s a certain release that happens when we are in the process of experiencing Junkanoo. The music, the dance, the artwork and the theatre, and the community of individuals all just releasing joy into the world.

My joy really comes from the sense of the resilience of my people. Joy is a very powerful word. In order for me to get the joy, I have to take a few steps because of where my mind is right now in my history. As I mentioned, I’ll be seventy-five years old my next birthday and so I’m on the other side of the mountain. I have a certain amount of time to say what I want to say, and I don’t want to pretty up the reality that exists. I love my people. I love the resilience. I love the fact that there is a community of human beings of all colours who are basically good people. I love that. There’s joy in that. However, I still come back to the fact that there is some young child being born somewhere in the world who happens to be Black and who is starting out with nothing because he’s Black and nobody seems to really care. For me, to get to joy from there is going to require me to take a few more steps. My joy is in my hope for the future. I don’t know if that paints a dismal picture.

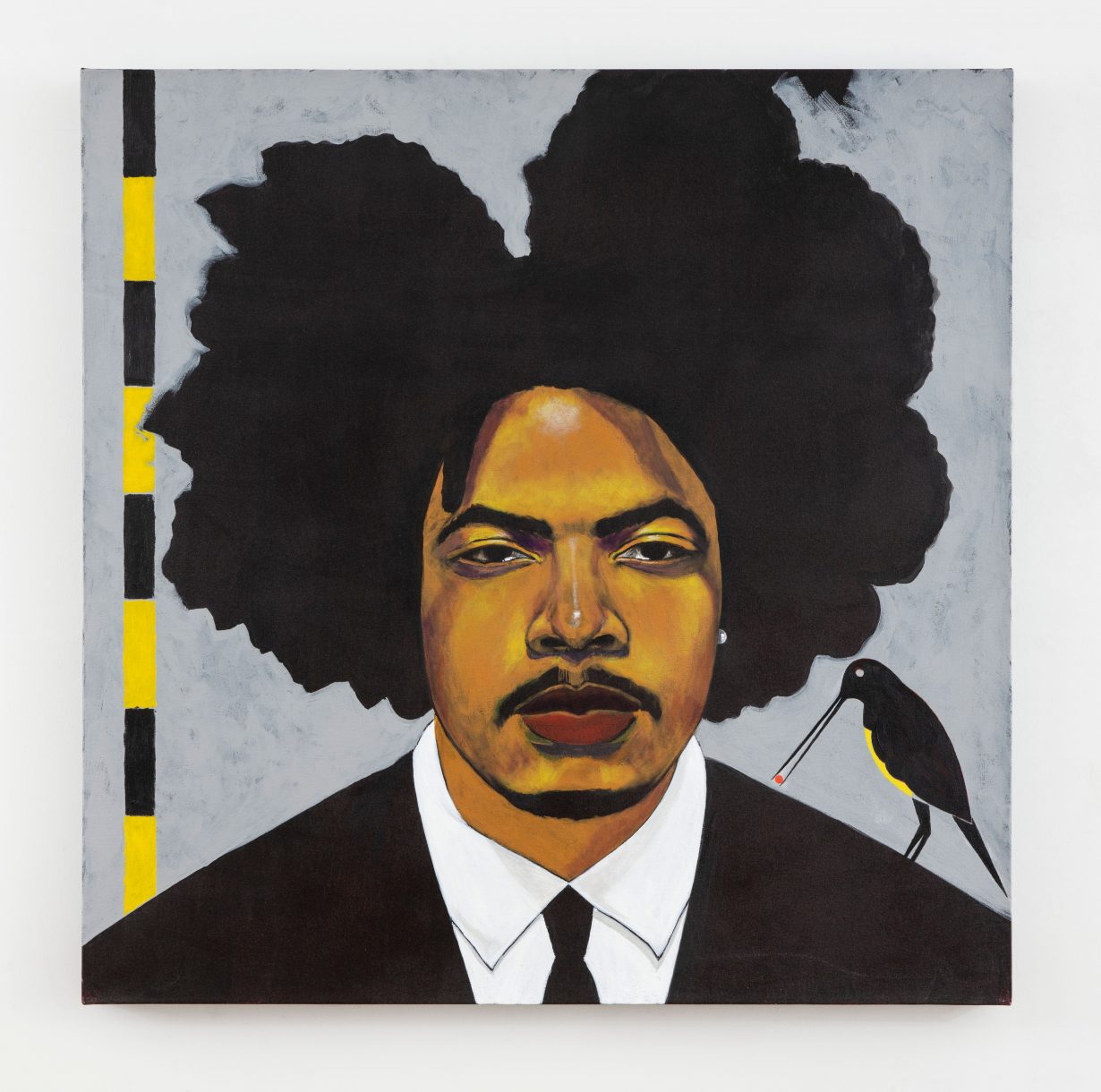

TS I don’t think it’s one or the other. I think it’s like trying to ask someone what their favourite colour is on the colour wheel. I think sadness and pain are parts of it. I think joy and happiness are parts of the whole experience. I think that’s not to discredit the suffering of anyone, but I think when I look at the paintings I see all of it. I don’t just see one side of it. That’s just my interpretation of it. I think you could see the appreciation for the characters and the love and the personhood and the paintings that are not all about pain and suffering. It’s about the human experience, which is varied.

I think that’s the beautiful thing about picture making. We’re not asking the painter to make meaning, we’re asking them to make the painting. We get to make meaning. The audience gets to make meaning. I think it’s a part of why art is so powerful, because if you think of it as a pyramid, you have the artist, you have the vehicle whether that’s an institution, or a gallery, or museum, or a public space, then you have the audience. I think if you take apart any of that triangle you don’t have a structure. I think all those things make the work. My reading of the work is to me as important as anybody else’s as a viewer. I’m seeing all of that pain but I’m also seeing all this joy. They could exist simultaneously.

SB Yes, I don’t think my work is completely joyless.

TS Stan, I’m not saying it’s joyless at all. I’m saying it’s full of joy.

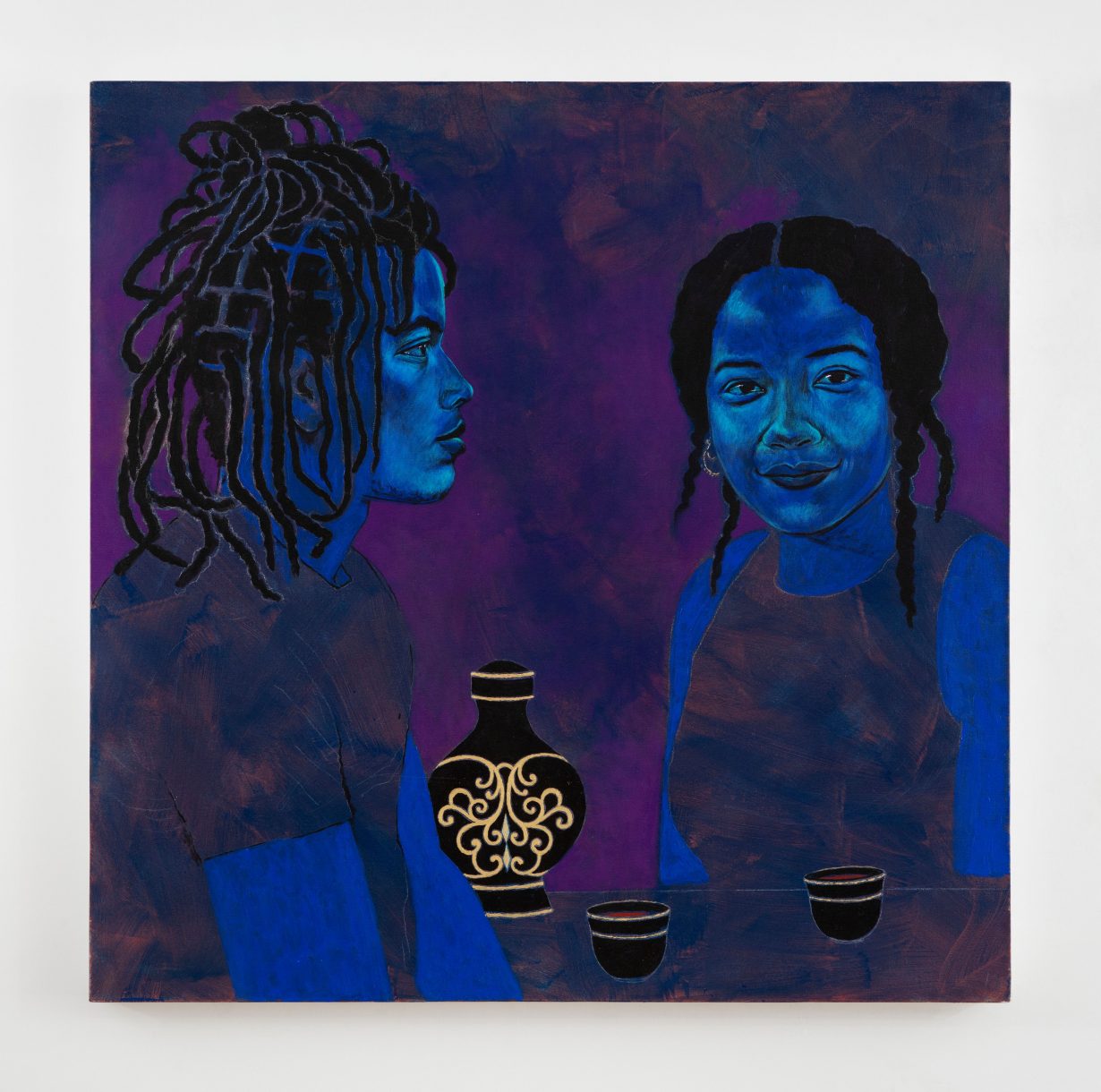

SB The way I express it, there’s a universal chord. Take a painting like Sibling Sanctuary (2021). It’s a brother and a sister who know what is going on in their individual lives, but they find a way to communicate and to be there for each other and support each other. That has very little to do sometimes with the fact that they happen to be Black, and more to do with the fact that they are siblings and they have this support system. They’re universal cords that I strike.

Tavares has this incredible ability. He has that Da Vinci thing, the odd in the science. He has an appreciation for the festival arts. He has almost the Romare Bearden thing where he’s able to riff and play with images and colour. He has a lot of different things going. When I think of it sometimes his view of the world is like when I’m maybe 30,000 feet in the air, he’s already all the way to Pluto in terms of the space that he has travelled. His view of the world is completely different than mine. I enjoy watching him travel the cosmos. To a great extent, I am an intuitive painter who is dealing with basic feelings about the world on a very, I guess, limited level. Limited in the sense that I can sometimes get so focused on the feelings that I’m trying to express that sometimes it becomes very narrow and provincial. What I’m saying is I’m very selfish when it comes to expressing myself. Hopefully, it doesn’t prevent people from recognising something in the work that they can identify with.

Stanley Burnside: As Time Goes On is on view at Perrotin, New York, through 23 December