Artists curious to understand what ‘commitment’ means in the practice, let alone the discourse, of the visual arts, would be wise to pay close attention to the work of Leigh Ledare, because no other young artist I’m aware of approaches artmaking with as much honesty as he does. But of course such words of praise demand defence.

This is easily mounted with the resources of the two projects presented at Mitchell-Innes & Nash. Neither body of work, Double Bind (2010/2012) or An Invitation (2012), is brand new, though this is the first time that either has been given a public airing in New York (Double Bind was shown in LA in 2012, and reviewed in these pages by Andrew Berardini; An Invitation has never before been shown in the US).

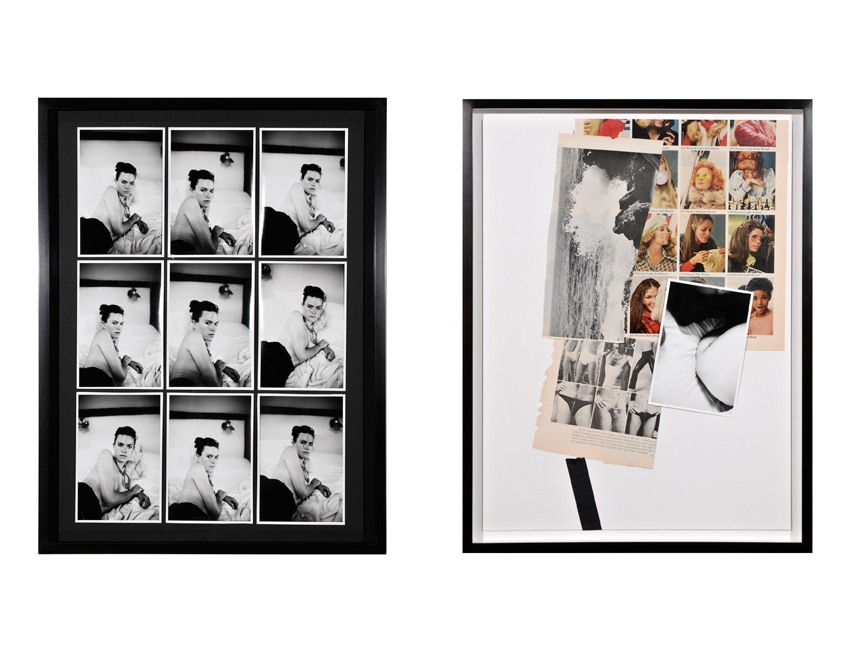

Both projects involve Ledare personally. For Double Bind, he spent time photographing his ex-wife during a short sojourn in a cabin in upstate New York. He then arranged for her and her new husband, also a photographer, to undertake a similar sojourn and photographic campaign at the same cabin. The results are juxtaposed against one another and clippings from old print magazines (from porno to fashion to culture). With An Invitation, Ledare accepted a commission from a European high-society couple to make erotic photographs of the wife (who is some 20 years her husband’s junior) over the course of one week in July 2011. A set of these pictures were kept by the couple, but as per their agreement, Ledare kept a set for himself and produced a series of screenprints that show the pictures, with the wife’s face redacted, juxtaposed against the front page of The New York Times from the days of the shoot.

Ledare hazards what we cheaply call ‘difficult situations’, not by staging them but by getting into them

There is much to be said about the language of photography in both cases, about questions of power, both statutory and otherwise (a redacted version of the contract and confidentiality agreement that subtends An Invitation is also on view, for example), and about the kinds of subjects that photographs and photographic imagery produce or interpolate. But in these projects – as well as others that Ledare has pursued, such as, perhaps most significantly, Pretend You’re Actually Alive (2008), a portrait of the fraught, Oedipal relationship that Ledare shares with his mother – there is always a palpable feeling of risk.

Ledare hazards what we cheaply call ‘difficult situations’, not by staging them but by getting into them. His aim isn’t transparency, however, but complication – at the affective rather than intellectual level. Ledare does work as much inside of photographic theory as practice, yet without his work becoming either esoteric or didactic, as so much contemporary conceptual photographic work does today. Perhaps this is because the central paradox of photography – this image is there, fixed; but its meaning can never be – serves Ledare as an amplifier of the many vulnerabilities – his own, those of his subjects, ours – that we all try to keep from public view.

This article was first published in the Summer 2014 issue.