How can India renew itself without properly coming to terms with its past?

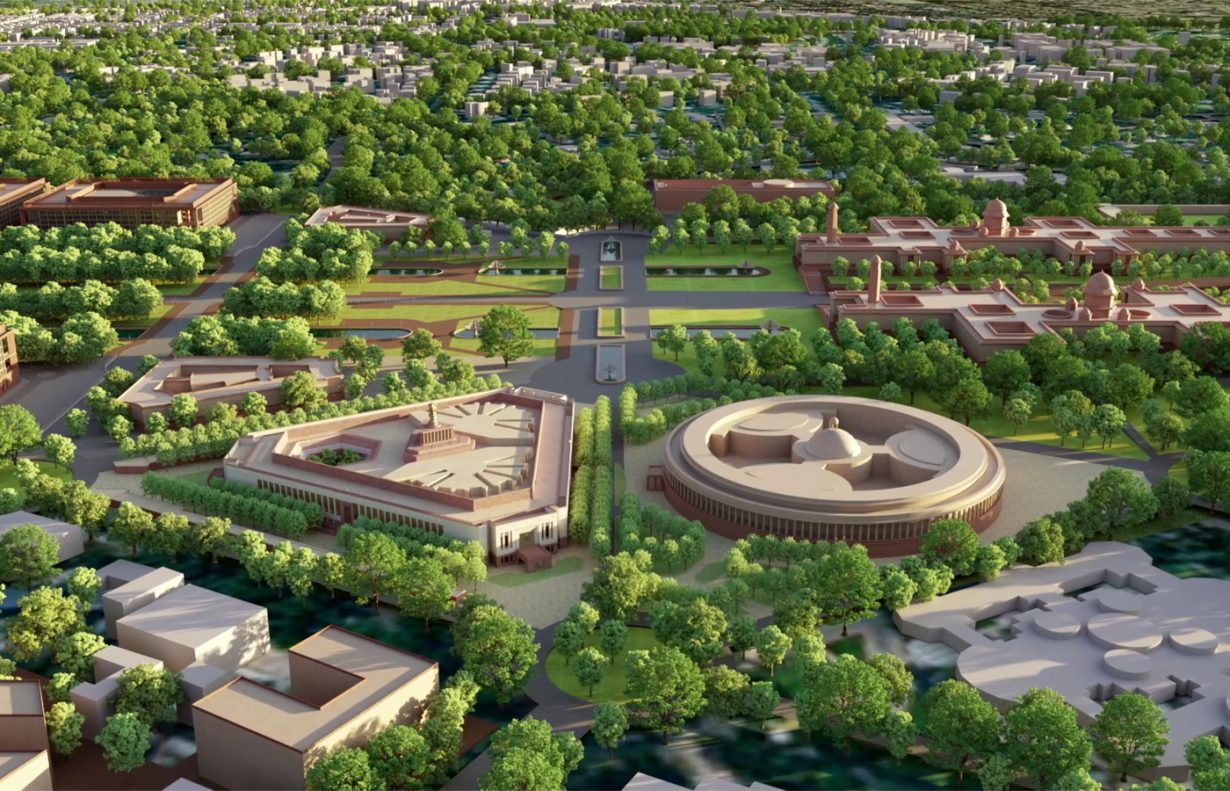

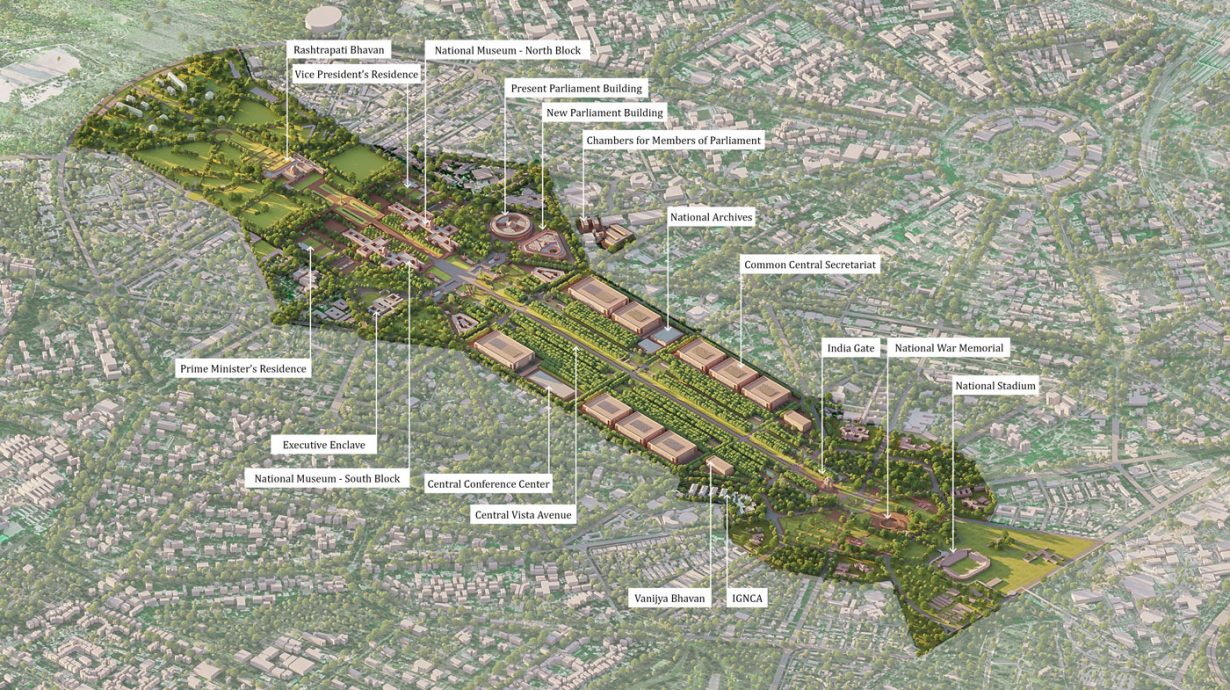

Roughly 16 months from now, in August 2022, when India celebrates her 75th year of Independence from British colonial rule, the nation is expected to have a new triangle-shaped Parliament building in New Delhi. It is to be built adjacent to the current Parliament, a circular structure marrying Palladian classicism with Indian subcontinental influences that was designed by British architect Edwin Lutyens, with Herbert Baker, in 1912–13 and constructed during the 1920s. By 2024 several new government buildings are expected to be completed along a three-kilometre stretch from the Rashtrapati Bhavan, the official residence of India’s president, on Raisina Hill to India Gate.

Together, the works in this Central Vista project will not only change the way central New Delhi looks but will seek to dismantle the history of Lutyens’s Delhi. During a period when a variety of movements are reexamining troubling histories in both former colonies and the global north, the treatment of India’s architectural legacy raises many questions: how to read the past, how a forward-looking nation can deal with colonial trauma, what constitutes a country’s heritage; and the larger questions of what gets preserved and why, and what gets erased, destroyed or rewritten, and by whom.

Lutyens was tasked with designing a capital city that would reflect the imperial ideal of the British Empire. While he did not think very highly of Indian styles, dismissing them as contradictory to the essence of fine architecture, he did employ several features that had been in use in India for centuries to adapt his buildings to the local weather, among them a water feature at the Rashtrapati Bhavan, an element of architecture influenced by Mughal styles. It is worth noting here that Lutyens was not the only foreigner to be tasked with building a new capital in India. Roughly four decades later, newly independent India’s prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru would invite Le Corbusier to design the city of Chandigarh, a joint capital for the two neighbouring states of Punjab and Haryana.

The current rightwing, Narendra Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government has increasingly been using a language of symbolism to drive its public-relations agenda. It’s a campaign for which 2024 is a significant year on two counts: Modi will go to the polls to seek a third term as prime minister, and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the ideological parent body of the BJP, will enter its 100th year of existence. Perhaps with that in mind, it has presented the very expensive and (given the pandemic of which we are in the midst) rather ill-timed Central Vista works as a ‘redevelopment’ project that will represent ‘the values and aspirations of a New India’, ‘rooted in the Indian Culture and social milieu…’ If Modi is able to orchestrate the completion of this remodelling of the city – the project includes a swanky new house for the PM – the boost to his personality cult, as the sage, fatherly leader (emphasised also in the long white beard he is growing) who knows what is best for his nation, might prove to be significant in an election year.

While the case for building more room for an expanding post-Independence national government has been made for some time now (and under the auspices of previous governments as well), the timing and the manner in which the Central Vista project was finalised have been much criticised in architectural, conservational and civil-society circles since the scheme was announced in late 2019. Modi has sought to blunt criticism by announcing that the old Parliament building, including the North and South Blocks designed by Herbert Baker and that now house the Secretariats, will be converted into museums that, it is rather vaguely promised, will showcase displays celebrating ‘India at 75’ and ‘The Making of India’. The current Parliament is, with no little irony, to be converted into a ‘Museum of Indian Democracy’.

Naturally all this comes at a cost: the budget for the project starts at INR 20,000 crore (10 million = 1 crore) of taxpayer money, an amount that might, according to critics of the scheme, be far better utilised battling the pandemic, rising unemployment, Delhi’s severe pollution levels or a dozen other problems facing the country. They argue, furthermore, that the principle of adaptive reuse should be applied to the existing Parliament building. And yet, despite the fact that opposition to the scheme is widespread, there is no stopping the Central Vista project now. In Delhi, land-use laws have already been hurriedly modified and public-interest litigations questioning the project quashed. With a go-ahead from the Supreme Court, the bhoomi pooja, a ceremony conducted before starting a build, has now been performed.

The Hindu ritual, photographs of which have been widely disseminated over mass media, is a troubling spectacle in a constitutionally secular nation, though this blurring of state and religion has become par for the course under the current government’s Hindutva agenda. In need of urgent deliberation now is the question of what gets to be chosen as heritage and culture in today’s India, and where one places imperial architecture within these politics of choice.

Architecture in India has rarely been accorded the same attention and importance as the other artforms. Except for centuries-old forts and temples, and perhaps the mild exoticisation of indigenous, rural architecture, the notion that buildings might stand as witnesses to a country’s evolution is not something that finds a prominent place in the public narrative of India’s cultural wealth. Even as debate for, but mostly against, the Central Vista project was raging, the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad invited designs to build new student dorms on campus, at the cost of demolishing older buildings designed by modernist architect Louis Kahn. After much international outcry, the proposal was dropped; Kahn’s influential aesthetic is safe, for now.

It is without doubt that buildings like Rashtrapati Bhavan and others of its ilk in the vicinity, as also others in cities across India, are imposing symbols of the country’s traumatic colonial past. The ideals around which they were designed are certainly not representative of an independent country. But deciding the fate of heritage structures that belong to the whole nation surely cannot be arbitrarily taken, without seeking public opinion, and without conservation being duly considered. It is tempting to close one’s eyes to history and wish away the pain of colonisation and its deep-rooted impact on everyday lives. But the legacy to be carried forward by Indians, as a nation, will be better served if the complexity of this history is understood alongside an acknowledgement that these buildings too are part of India’s very recent past and need to be conserved and learned from. The willingness with which parts of history that a section of people don’t like are slowly being erased is but a dangerous act of manipulation against the larger populace. If anything, it is only paving the way for a future characterised by further, newer trauma.