Our editors on the exhibitions they’re looking forward to this month, from Adrian Piper and the late Ryuichi Sakamoto to the 14th Bamako Encounters biennial

Ryuichi Sakamoto: seeing sound, hearing time

Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, 21 December 2024 – 30 March 2025

A year and a half after musician and composer Ryuichi Sakamoto’s passing comes seeing sound, hearing time, an exhibition of his largescale installations, initiated later in his life, and the first show in Japan dedicated entirely to these room-size attempts to give space and visibility to sonic processes. Spanning synth-pop, operas, sweeping film scores and minimal-glitch (and still touring from beyond the grave with his augmented reality concert performance KAGAMI, 2023), Sakamoto’s work now gets the art institution treatment. The exhibition shares a name with an exhibition of his installation works that toured from Beijing in 2021 and Chengdu in 2023; this iteration of the show includes works like life – fluid, invisible, inaudible… (2007/21), created with longtime collaborator Shiro Takani, which remixed elements of his 1999 opera Life into a series of visuals refracted through a set of suspended water tanks, alongside newly realised work conceived by Sakamoto shortly before his death. Chris Fite-Wassilak

Adrian Piper: Who, Me?

Portikus, Frankfurt, through 9 February 2025

In 1969, Robert Smithson laid a dead pear tree horizontally along the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf gallery floor. Over ten metres long, and its noodle-roots and twiggy arms interspersed with various small mirrors, Mirror Displacement: Indoors would lay to rest for the exhibition’s duration – air discolouring the bark and the central heating peeling its skin. At Portikus in Frankfurt half a century later, the American artist and philosopher Adrian Piper updates Smithson’s work for our times. In I’m the Tree, a stalk and all its rhizomes is suspended in air, held aloft a mirrored floor by a system of metal cabling and walled-off by a temporary rectangular box – viewers can only peer in from a higher mezzanine. Cold white lighting, amplified by the mirroring, makes the ash bark and wintry branches feel nakedly, clinically exposed; viewers inevitably catch each other in reflecting sightlines, or a new perspective on the branches against the gallery’s concrete roof, inverted along the floor. A pathway through art history – from Smithson’s Mirror Displacement to Piper’s I’m the Tree – can be traced in this latest work: Maria Eichhorn’s spatial interventions like Redundant Stairs, 1987; Lucas Samaras’s use of mirrors in Mirror Structure – Embrace (1991–2005). In many cultures, the tree is of course the great metaphor: family, home, community, security, hope, ‘Mother Nature’, Eden. If Smithson’s work was a body found dead, Piper’s is an open casket. Alexander Leissle

Carmen Amengual: A Non-Coincidental Mirror

Co-presented by Smack Mellon and the Vera List Center, New York, 7 December 2024 – 9 February 2025

In December 1973, film directors from various countries including Argentina, Cuba, Mauritania and Senegal travelled to Algiers for the First Third World Filmmakers Meeting, to discuss strategies for countering the ideological and economic pressures of neocolonialism in cinema. The Los Angeles-based interdisciplinary artist Carmen Amengual enters this episode in time via the letters and photographs of her late mother, an Argentinian architect who’d had a hand in organising the Algiers assembly. Amengual has previously invoked her mother as a spectral interlocutor in her 2018 exhibition The Tenuous Arithmetics of Kinship – for which the artist recreated photographs her mother took in the 1970s in what was described as an ‘attempt to re-perform a gaze’ – and explored the Third World Filmmakers Meeting in past works such as Fragments from Algiers (2019–), a black-and-white Super 8 film on her mother’s years in Algeria with a group of filmmaker-activist friends, Now, she will present a film installation at Smack Mellon as part of her first US solo institutional exhibition, A Non-Coincidental Mirror, that again probes political history from a personal and familial angle. At a certain point in the film, the camera acts as an interloper, recording the stairs of a residential building through what appears to be a hole in a nearby wall, producing an image that brims with the longing and urgency of a researcher one generation removed from the action, who must re-perform and reconstitute a gaze using the few but precious tools she has inherited. Jenny Wu

14th Bamako Encounters: Kuma, the Word

Various venues, Bamako, through 16 January 2025

Africa’s first and largest photography biennial, Bamako Encounters, returned for its 14th edition last month. Titled Kuma, the Word, this year’s biennial, which spotlights photography and video by African artists from across the continent and its diaspora, includes a central group exhibition of 30 artists whose works blend ‘verbal and visual storytelling’ and ‘experiment with how words in all their forms – spoken, written, sung, or rapped – can coexist and resonate within the photographic medium.’ Expect to see works by the likes of Nigerian photographer Victor Adewale, who’s known for his photo series documenting the lives of overlooked communities such as Lagos’s gradually marginalised motorcycle taxi drivers in Ebi OlOkada (Okada Family, 2021); meanwhile, Jeannette Ehlers presents Black is a Beautiful Word. I & I (2019), a photography and video installation based on a 1900 photo in the Royal Danish Library’s Collection – of a maid from St. Croix named Sarah – that explores colonial legacy as well as ‘connectivity within the African diaspora’; and Primo Mauridi (from the Democratic Republic of Congo) explores the mythology surrounding Mount Nyiragongo, a volcano located close to his home city of Goma, as well as ancestral rites and local ecological concerns through the project Mawe (2022), which takes the form of an installation of digitally manipulated video and photography. Fi Churchman

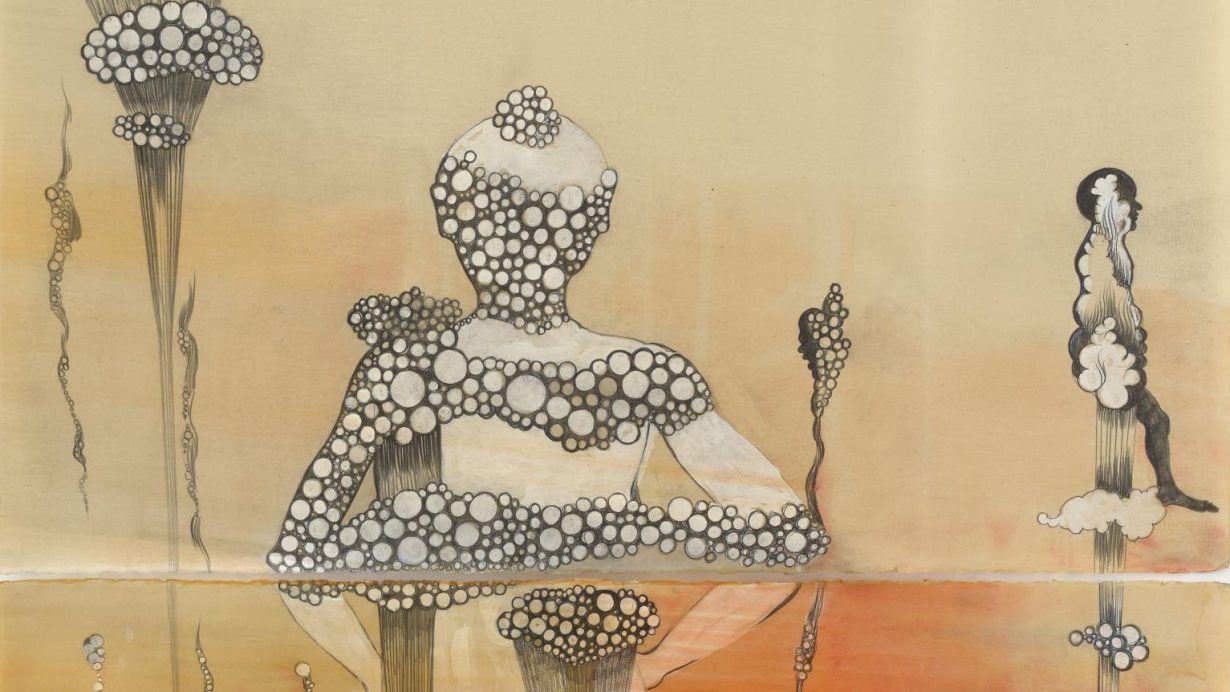

Sandra Vásquez de la Horra: Los volcanes despiertos

Museo de Bellas-Artes de Chile, Santiago, 6 December 2024 – 9 March 2025

What does the woman with a stag’s head over her private parts want with us? Why does the dog nip at the heels of the naked man? Is it because he carries a sack filled with babies? Who is the god with the long beard who hovers above a mountain range? Each Sandra Vásquez de la Horra drawing, invariably sealed with wax, raises a dozen or more questions, but most might be answered by the counterquestion that seems to drive the veteran Chilean artist: where did we all come from? The artist’s compositions, intermingling diverse cosmologies and creation stories, attempt to answer the existential and unanswerable. This retrospective, featuring 190 works, stretches from Vásquez de la Horra’s early drypoint and aquatint etchings on paper series, The Voyage (1986), depicting the moment of conception; and her 1990s post-apocalyptical or pre-human fiery landscapes (one of which, The Volcanoes Awake, 1992, lends the show its title); to her mythical figures of the 2010s and the most recent dioramic sculptural works of wax-stiffened paper showing the naked female form. Oliver Basciano

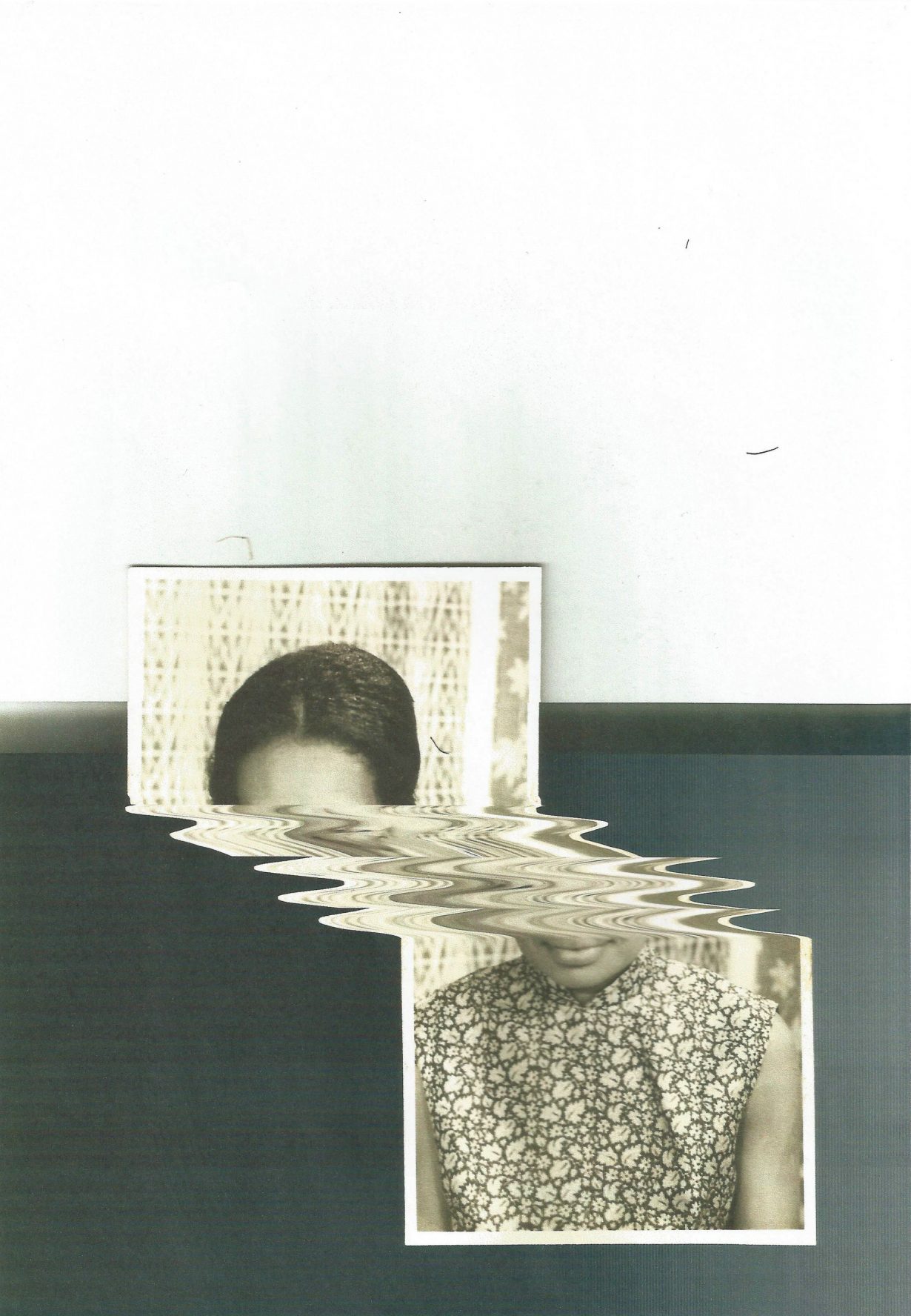

Helen Cammock, Ingrid Pollard and Camara Taylor: Soft Impressions

Dundee Contemporary Arts, Dundee, 7 December 2024 – 23 March 2025

In London, studio size has halved since 2020, while soaring rents have led many artist studios to close altogether. In Hackney, East London, the now-shuttered Lenthall Road Workshop, started by three women in 1975, offered darkroom and screen printing facilities to Black and working-class women. Artist Ingrid Pollard began her career at the studio, working with others in the community to give visual shape to their political activism through the printing of posters and banners. Now seventy-one, Pollard is one of three artists from different generations whose work forms part of Soft Impressions at Dundee Contemporary Arts (DCA), alongside Helen Cammock and Camara Taylor. Each explores printmaking as a tool for activism, as well as how popular media has shaped common perceptions of race. In one series, Cammock replicates in a montage the historical print media portraits of African-American abolitionist Frederick Douglass, squaring with print’s role as a means of propaganda – for better and for worse. While in a work by Taylor, a distorted digital print of a member of the artist’s family is printed with the black ink removed from the toner cartridge, using the medium itself to question the unstable construction of the image. The focus of the exhibition highlights a resurgence of interest in printmaking, even at a time when the cost of the processing and printing of analogue camera film is sky-high and facilities are scarcer than ever. It also serves as a reminder of the value of these community spaces (both Cammock and Pollard spent time in residence at the DCA’s own print studio in the run-up to the exhibition), and the intangible relationships that are lost when these disappear. Louise Benson

The 11th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art

Queensland Art Gallery & Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, Australia, 30 November 2024 – 27 April 2025

A triennial without a theme – how refreshing! Especially given the constant narrativisation of largescale exhibitions, and the framing of these themes within ‘chapters’, subthemes, questions, categories etc. It might seem daunting, then, to navigate the works of more than 200 artists at this year’s Asia Pacific Triennial, but at least you’ll know that it generally revolves around ‘new art from the region’. Though, what’s to say a ‘region’ couldn’t be considered a theme? Because: what is a region? How is that geography defined? Who decides what makes a region and can that region expand or contract? I’ll leave those questions to be answered by the artists showing at APT, who represent ‘the complex interwoven cultural landscapes of Australia, Asia and the Pacific’, and whose works are installed across both Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art. Of particular interest, not least because of last week’s 40,000-strong protest in Wellington by advocates of Maori rights against a proposal to rewrite New Zealand’s founding constitution: artist Brett Graham (whose work I first learned about at this year’s Venice Biennale; his wooden sculpture, Wastelands, 2024, of a cart piled high with a what appeared to be a writhing mass – of eels, it turned out – was included in the main exhibition) will be presenting Tai Moana Tai Tangata (2024), a video, image and sound installation that reflects on ‘the ways in which the resources of the Tainui and Taranaki Maori were extracted to make wealth for the colonial powers during the New Zealand wars of the 1860’. And, speaking of people losing agency, Thai artist Kawita Vatanajyankur will be premiering a new performance titled The Machine Ghost in the Human Shell at ATP – here, the artist’s movements will be controlled by an AI programme, presenting an enquiry into what might happen if machine intelligence can be merged with the human body, and who, or what will ultimately have control over the soul. Fi Churchman

Yasumasa Morimura and Cindy Sherman: Masquerades

M+, Hong Kong, 14 December 2024 – 5 May 2025

Given that the work of both Yasumasa Morimura and Cindy Sherman consists of self-portraits in which each artist assumes the appearance of someone they are not (or what M+ call a ‘masquerade’), it’s surprising that no institution has previously presented their work in a two-person show. Particularly given the concrete links between the two: Morimura’s To My Little Sister: For Cindy Sherman (1998) is a staging of the American artist’s iconic Untitled #96 from her Centerfold series of 1981. The work is like a set of Matryoshka dolls, in which Morimura becomes Sherman who was, in the original work, herself becoming a B-movie actress. While both artists were once cast as heralds of the media age, now they appear also to have anticipated the world of deepfakes and the more sinister uses of AI. Each artist uses their work to highlight often-invisible social divisions of class, power and gender, both as they manifest today and through history, with the Japanese artist additionally exploring the interface (or lack of it) between the cultures of the East and the West. Collectively, their work focuses on the superficiality and arbitrariness of identity as it manifests in physical form, as well as the ideologies that go into constructing it. Ultimately, both also spotlight the importance our cultures continue to attach to identity, even if we know it is all made up – unsure whether we are constructing it for ourselves or part of the constructions imposed by others. Nirmala Devi

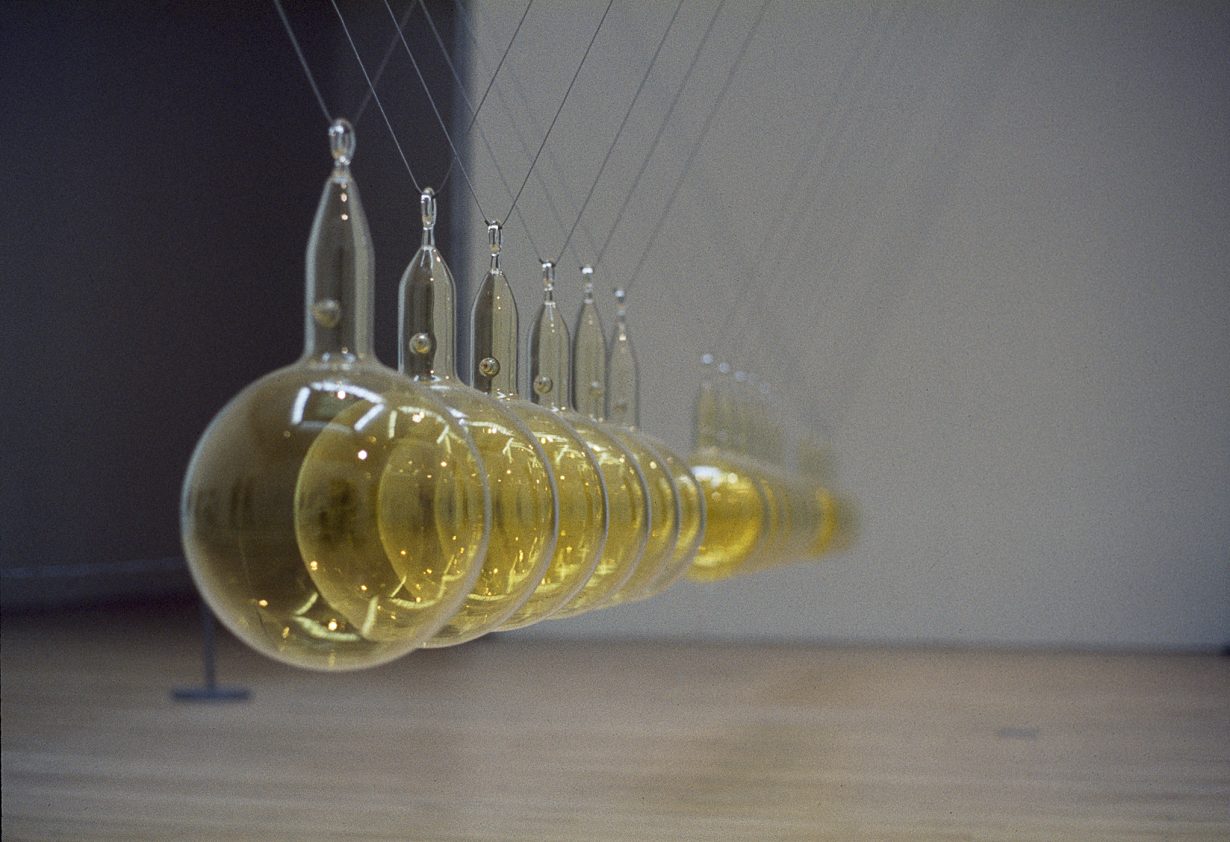

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions

IMMA, Dublin, 6 December 2024 – 5 May 2025

Three separate rows of glass balls are suspended from steel wires in the form of Newton’s Cradle, as if waiting to be knocked together. The spherical objects have a yellow tinge; accompanying information on Familiars Part 3: Cradle (1992) will inform you that each one is filled with lethal chlorine gas. The installation sums up a core theme of the sculptures of British artist Hamad Butt (1962–94): an inviting playfulness that is undercut with precarity and danger. Born in Lahore and raised in Essex, Butt trained as a biochemist before studying art at Goldsmiths where his classmates included those who went on to be recognised as YBAs, after the seminal exhibition Freeze was organised during Butt’s second year at college. His work shares the high-impact visuals of that period: in the kinetic sculpture Familiars part 1: Substance Sublimation Unit (1992) iodine gas makes a ladderlike structure glow bright red. Yet it also contained more subdued references to Butt’s Muslim upbringing and experience as a queer man. This exhibition brings together his installations and roughly figurative paintings, which anticipated current concerns with infection, risk and boundaries – and is reflective of a promising trajectory (Butt passed away in 1994 due to AIDS-related illness). The exhibition marks the first time that Butt’s work has been shown outside of England and is coorganised with London’s Whitechapel Gallery, where it will travel next year. Chris Fite-Wassilak

London Contemporary Music Festival

Various venues, through 17 January 2025

In a world where the arts seem to prioritise accessibility over all other considerations, for ten years the London Contemporary Music Festival has been an unashamedly highbrow event where experimentation, discovery and a lack of condescension have been its defining features. This year the 18-day festival has the loose theme of the trickster. ‘Shapeshifter, border-crosser, mischief-maker, lord of misrule, god of the in-between, catcher of contingency, vandal, joker’ write the festival’s organisers, critic Igor Toronyi-Lalic and composer Jack Sheen; a description that might also apply to the perennial persona of their project. Jesters to the court in 2024 include minimalism pioneer Charlemagne Palestine performing a new work for the organ at festival HQ Hackney Church, while 92-year-old French avant-guardsist Éliane Radigue will premiere a chamber composition across town in Wigmore Hall. Further commissions include a film by Amalia Ulman, audio works from Matt Copson and a performance lecture by Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster. Decidedly older fare comes in the form of Dengbêj Kazo’s exploration of the 5,000-year-old art of Kurdish dengbêj-singing and Melinda Maxwell’s performance of the aulos, the wind instrument that accompanied Plato in his dying moments. Oliver Basciano