Our editors on the exhibitions they’re looking forward to this month, from the Venice Architecture Biennale to Gallery Weekends in Berlin and Beijing

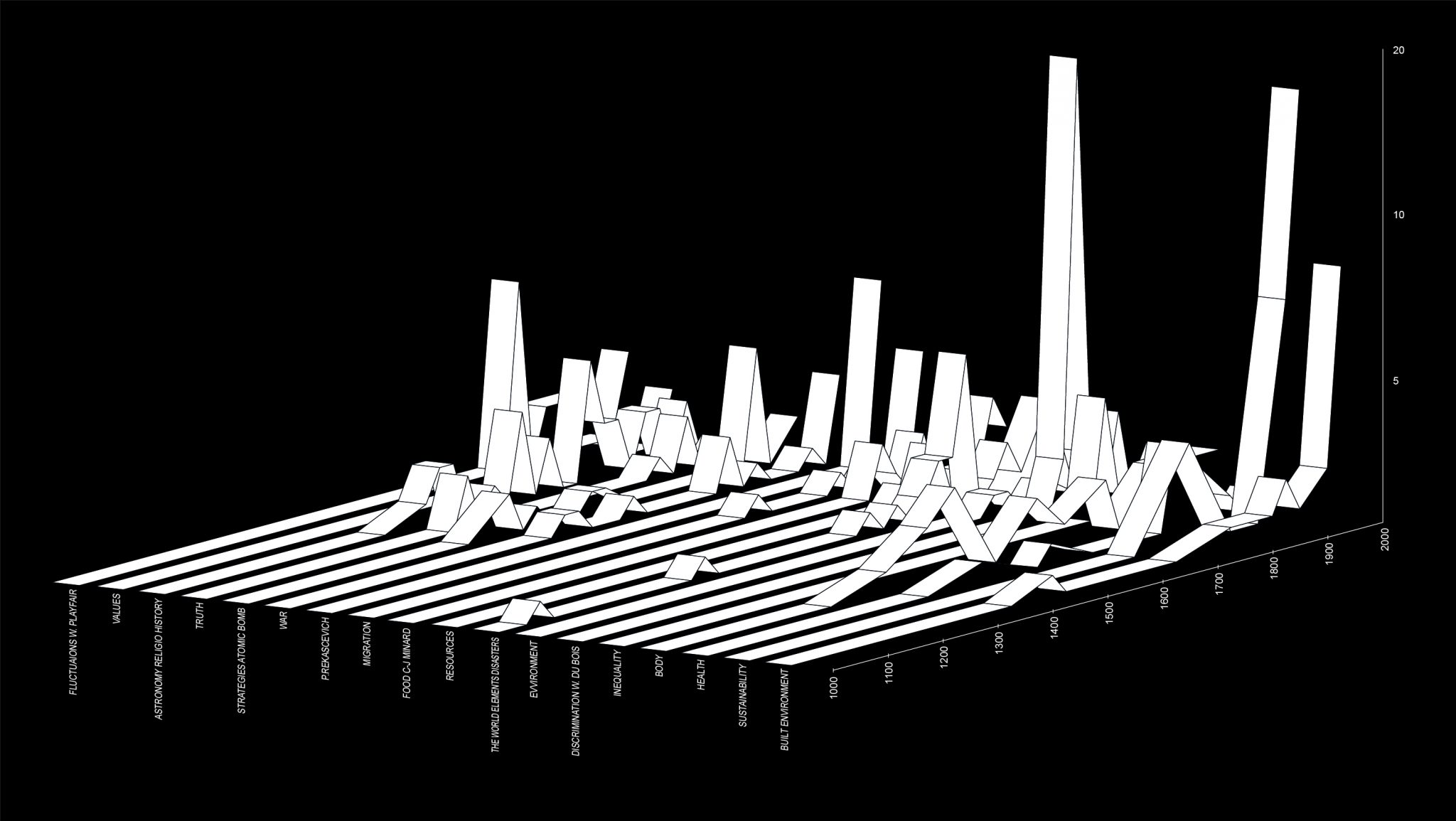

19th Venice Biennale of Architecture: Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective; AMO/OMA: Diagrams

Various Venues, 10 May – 23 November; Fondazione Prada, Venice, 10 May – 23 November

This year’s edition of the Venice Biennale’s International Architecture Exhibition is curated by architect, engineer and urbanist Carlo Ratti, the first Italian to do so in two decades (which to some is a backwards step from the growing internationalism of the past few editions). Smart cities are Ratti’s bag, and he teaches in the US, at MIT where he directs the Senseable City Lab. And Ratti’s ‘mission’ here is to argue that we should not follow the fashionable flock who can no longer read the word ‘intelligence’ without seeing the word ‘artificial’ automatically stapled in front of it. Rather he wants us to think about the world as part of a Venn diagram of intersecting sets labelled with all the words in his title. It’s like some old-fashioned back to basics campaign. Buildings! Cities! Planning! Talking of which (the basics), and for those of you who are into diagrams, there’s a whole show of them in an exhibition conceived by Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas’s studio AMO/OMA, running in parallel to the Biennale, at the Fondazione Prada. Their theory is that data = analysis = meaning. Or something like that. You probably need to be there to figure it out; it’s not like representations are a substitute for the real thing. Unless you’re at a biennial. Or a TED talk. In which case they are. Nirmala Devi

Gallery Weekend Berlin 2025

Various Venues, 2 – 4 May

It’s gallery weekend season, baby: Paris, Amsterdam, Beijing, but first up is Berlin. Watch the news and it would seem Berlin’s not been doing too well of late. It’s the city of radical freethinking, cultural innovation and unfettered hedonism – unless you’re, respectively, protesting genocide, dependent of state funding, or out of earshot of your fintech nachbarn or megalandlord. So we might want to focus instead on those using art to tell the untold, or the untellable. The Indigenous American artist Sky Hopkina – whose Cowboy Mouth (2022) series of inkjet prints were a highlight of the recent Widening the Lens landscape photography survey at Carnegie Museum of Art – will show a new film and recent photographs in Bone & Light at Tanya Leighton. In Cowboy Mouth, Hopkina laces warm, colour-saturated tableaux of rural American with passages of concretelike poetry in white handwriting, each of them new additions to the Indigenous American poetic tradition (Hopkina is a member of the Ho Chunk Nation). His is a kind of visually flamboyant Gothic, rehaunting technologies of modernity (photography, cinema and its techniques: montage, focus, perspective) with Native language, philosophy and spirituality. Meanwhile at Kunstraum Kreuzberg, Meduza, a team of journalists exiled from Russia, have curated No, an exhibition and research project documenting the experience of living under a fascist regime. Germany’s own ties to Russia significantly compromised its pre- and postwar response to Vladimir Putin. What, one wonders, might Meduza have to say about censorship and authoritarianism at home, as it begins to rear its head in ‘liberal’ Europe? And a new exhibition and study group at Spore Initiative, Unsettled Earth, foregrounds agrarian initiatives and collectives in Palestine to address how settler-colonial violence attacks land and those who work it – and, by extension, to explore pathways toward ending such domination, violence and ecological destruction. Such study – of history and a speculative future – are vital acts of epistemic defiance against those who would see Palestinian autonomy erased, and land razed. Alexander Leissle

The Gatherers

MoMA PS1, New York, through 6 October

The Gatherers, featuring 14 international artists working in assemblage, installation, video, performance and painting, is something of a wake for postwar globalisation and neoliberalism. In lieu of a body, what we have in the former schoolrooms of MoMA PS1 are rows, piles, fragments and amalgams of humanmade detritus – at times lovingly recycled, by artists like Geumhyung Jeong, Ser Serpas, Tolia Astakhishvili, Nick Relph, Miho Dohi and Jean Katambayi Mukendi – and documentary footage of defunct infrastructure. Emilija Škarnulytė’s single-channel video Burial (2022), an example of the latter, is an hour-long exploration of the Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant in Lithuania, which was built in the 1980s and decommissioned at the start of the twenty-first century because its reactor design was found to resemble that of Chernobyl. A more cathartic kind of funereal gesture could be found in Selma Selman’s performance Motherboards (2025), for which she and a group of collaborators took hammers to discarded circuit boards, freeing the precious metals inside them. Meanwhile, Karimah Ashadu’s single-channel video Brown Goods (2020), which follows Emeka, an Igbo Nigerian economic migrant in Hamburg working for a West African exporter of German refuse – used cars, old kitchen appliances – highlights the human labour involved in tending to the ghosts of ‘global waste and excess’. Jenny Wu

Tina Girouard: SIGN-IN

Museo Tamayo, Mexico City, 21 May – 14 September

The American artist Tina Girouard (1946–2020) is not a name that many will recognise from museum shows or biennials of recent years. An active figure of 1970s downtown New York, the Louisiana-born Girouard was a cofounder of the artist-run restaurant FOOD, and contributed to the beginning of 112 Greene Street, the experimental performance studio that became known as White Columns in 1979. Her work was rooted in collaboration, as seen in early performance pieces like Air Space Stage (1972) that saw her hang fabrics from suspended slats for performers to balance and swing from. A devastating studio fire in 1978 saw Girouard leave the city and return home to the American South, where she continued her textile and performance-based work. The subdued interest in Girouard from the international artworld following her departure from New York offers a stark reflection on the industry’s geographic centres of power. One institutional exhibition, at the Museo Tamayo in Mexico City in 1983, broke the mould – the museum’s first solo exhibition dedicated to a female artist. Forty years on, the artist’s work returns to the museum for a retrospective that illuminates her lifelong interest in the notion of ‘maintenance’ and upkeep as a way of affirming the spirituality of everyday objects and interactions – notably in the Maintenance video series (1970-76) in which she filmed herself performing domestic tasks such as cutting her hair or doing laundry. First premiered last year at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans, SIGN-IN explores the full arc of Girouard’s life and work, in which the ‘local’ production of art is placed in deliberate opposition to a larger institutional system of influence. Louise Benson

Gallery Weekend Beijing 2025

Various Venues, 23 May – 1 June

After rumours of personnel changes, financial crisis and even speculation that it might not be happening altogether, Gallery Weekend Beijing will be back, and, in fact, bigger. This year it coincides with art fairs Beijing Dangdai, Art021 Beijing as well as 798CUBE’s Art and Science Biennale, and numerous institutions are putting on their best for the season – from UCCA’s Anicka Yi survey to Red Brick’s Chiharu Shiota takeover. The participating galleries this year, meanwhile, are, as always, proudly domestic. Galerie Urs Meile will be showing Wang Xingwei, whose wry, nihilistic humour has led him to paint pictures of romantic encounters on hoverboards (The Encounter of Life, 2018) or football fan posing next to China’s imperial ruins (Fan Emperor Rossi, 2022), inheriting a style mixed between socialist realism and Republican era satirical cartoons that’s typical of his generation of artists. On the younger side, Tabula Rasa presents Tant Yunshu Zhong, whose formalistic arrangements often piece together building materials and kitschy ephemera – materials that would be familiar to those who grew up in China’s increasingly urbanised environments; while Shanghai’s Antenna Space will occupy a decommissioned space in the middle of the district, mounting side by side new works by diasporic artists Xinyi Cheng and Evelyn Taocheng Wang. Spurs Gallery dedicates one floor of its space to Chinese artist Ye Linghan, and the other to Vietnamese filmmaker Nguyễn Trinh Thi’s 47 Days, Sound-less (2024), a three-channel video installation that weaves together various ‘marginalias’ of screen culture: pieces of natural landscapes, uncredited passersby and transient sounds of bugs and birds – all placeless backdrops she gleaned from Vietnamese and American movies. Amid the audio-visual pastiche is her documentary footage of Vietnam’s Indigenous Jarai villagers commemorating their dead, asking how we might, or might not, be able to really inhabit a place today. Yuwen Jiang

Dala Nasser: Xíloma. MCCCLXXXVI

Kunsthalle Basel, 16 May – 21 August

The Adonis River and the Qana Cave, both in Lebanon, are geographic elements that over millennia have been imbued with human stories: places where, respectively, Adonis was killed and where Jesus turned water into wine. From each, humans have sought different kinds of evidence captured, in a range of means; these are sites of myth, religious tales, and waves of contested histories that have been spoken, written, and later photographed, videoed, Instagrammed. The Lebanese-born artist Dala Nasser offers another means of documenting and re-narrating these sites, enacting a sort of inhuman archaeology that makes use of soil, rocks and plants. Her recent works have taken rubbings from rocks and ruin facades, onto fabrics dyed with spartium and oleander flowers, blueberries and walnut shells found nearby. Her contribution to the Carnegie International in 2022 was The Tomb of King Hiram (2022), a wooden frame draped in stained shreds of cloth, approximating the ruins that remain of the ninth-century BC royal grave in Qana, southern Lebanon. Her installation at Kunsthalle Basel attempts a similar reconstruction of the sixth-century Byzantine church that once stood nearby the tomb, the cloths giving it shape marked with inverted imagery of cyanotype printing. As an uneasy ceasefire currently holds between Lebanon and Israel, Nasser offers another way to think about where we might be in another 1500 years. Chris Fite-Wassilak

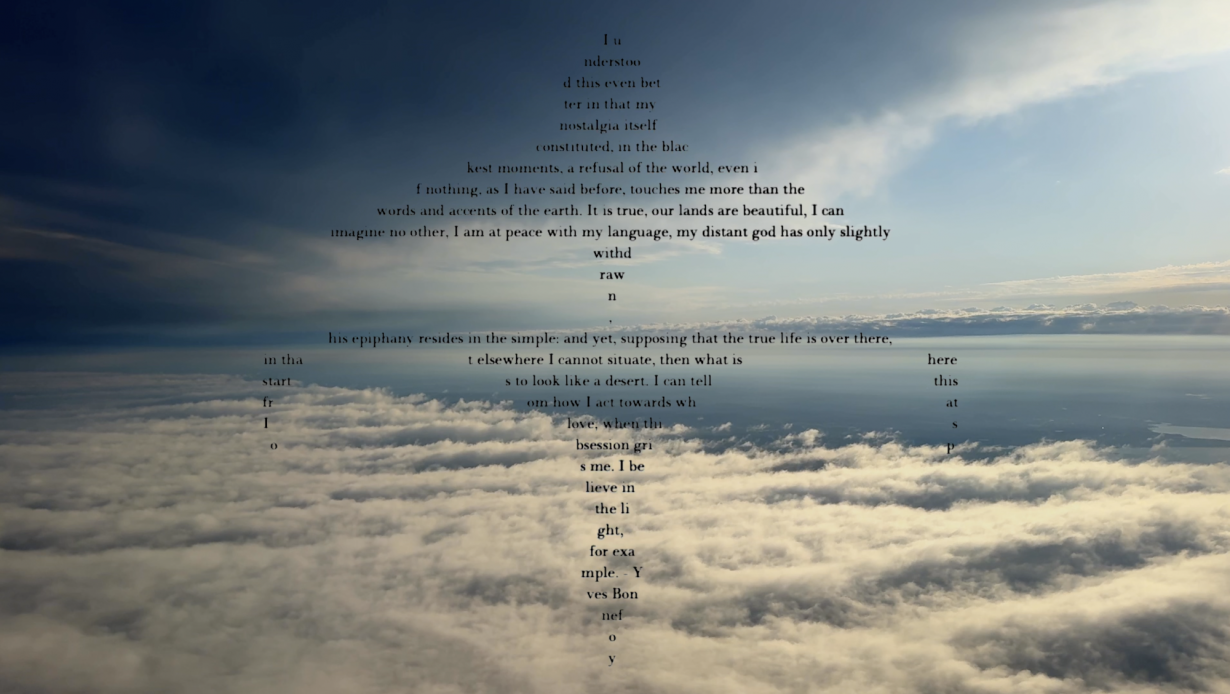

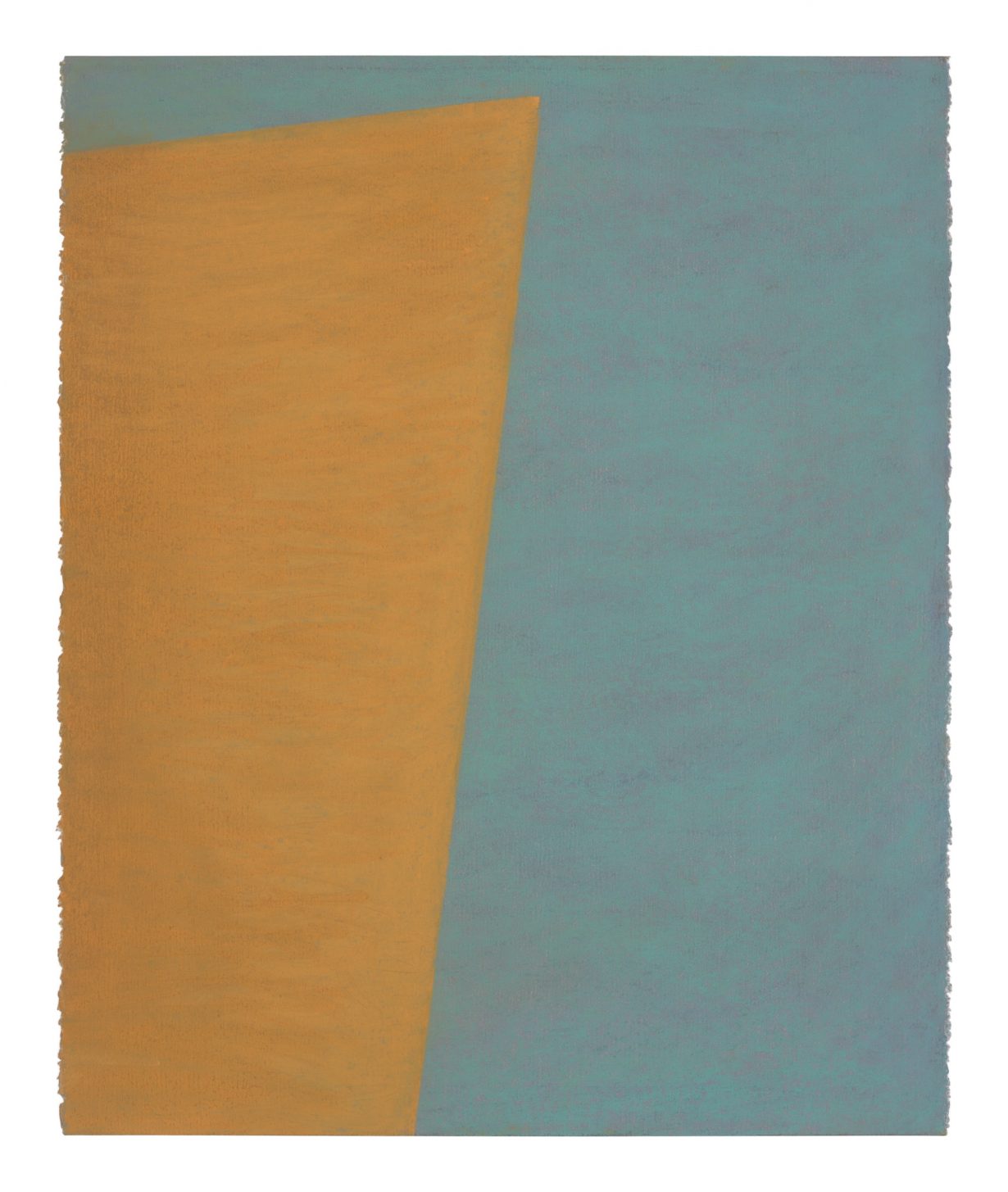

Ching Ho Cheng: Tracing Infinity

BANK/MABSOCIETY, New York, 2 May – 14 June

Tracing Infinity is a show of Ching Ho Cheng’s gouache and pastel works on rag paper dating between 1978 and 1982. Rendered in thin, almost airbrushed layers of pigment, these minimalist pictures come from a period in the Havana-born artist’s oeuvre which saw the subject matter of his work reduced to the interior of his living space. They succeed and counteract the elaborate ‘psychedelic’ paintings Cheng created in the early 1970s and presage his ‘torn paper’ and ‘alchemical’ experiments of the 1980s. In the abstract pastel works on view at BANK NYC, light is arrested and compressed into wedges of rust, marigold and pink. Figurative gouache works like Untitled (Window Diptych) (1980) contain details such as a grubby plastic light switch painted at two different times of day. In a horizontal blue hour gouache from 1982, a nail left in the wall looks from afar like a tiny human figure traversing an expansive void, casting a shadow four times its height. One may not be able tell from looking at these spare works that they depict a room in the Chelsea Hotel in New York, where Cheng lived from 1976 until his death in 1989, and that behind any of Cheng’s depicted walls might have been a raucous party attended by the likes of Andy Warhol, David Hockney and Charles James. Cheng was not, in any way, a recluse in his daily life, but his works here evince a profound familiarity with solitude. Jenny Wu

Rambert x (LA)HORDE: Bring Your Own

Queen Elizabeth Hall, Southbank Centre, London, 7–10 May

In one way, this collaboration between the UK’s Rambert and French collective (LA)HORDE, takes the former back to its roots. Rambert’s founder, Marie Rambert, spent her formative years as a dancer in Paris. In general however, (LA)HORDE specialise in breaking boundaries. Its work, which is very much embedded in the postinternet contemporary, takes the form of choreography and performance (it directs the Ballet national de Marseille, which performs alongside Rambert here) as well as video installations and exhibitions, and, accordingly, is as likely to be showcased in an art institution as much as it is in a theatre. Bring Your Own features a new work, Hop(e)storm, created for Rambert’s dancers, which offers ‘the spirit of Lindy Hop viewed through a postinernet rave lens’, apparently (the mind boggles) as well as stagings of two of (LA)HORDE’s classics, Weather is Sweet (2023) and Room With A View (2020). Nirmala Devi

Setouchi Triennale

Various venues, Islands of the Seto Inland Sea. Spring: until 25 May; Summer: 1–31 August; Autumn: 3 October 3–9 November

Visitors to biennials and triennials sometimes complain if the task of seeing everything in the show in question takes more than two or three days. It’s doubtful if the Setouchi Triennale can be seen in such a compressed timeframe, but luckily it’s on for eight months in three seasonal ‘sessions’ of spring, summer and autumn. A huge mutli-site festival of outdoor and public art (something of a trend in Japan, see the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial), driven by regenerations agendas, it straddles a total of seventeen islands and coastal areas of the Seto Inland Sea, the waters between Japan’s islands of Honshū and Shikoku, and sites on the coast of Shikoku. It’s a triennial that’s as much about appreciating the landscape and culture of the region as the art, in an area that has historically suffered the downsides of economic development and globalisation, with pollution and depopulation becoming significant problems. Artistically, it means artistic commissions that, over its six editions since 2010, has sought to bring both a sense of fun and an attention to the social life of its coastal venues, many of these the port towns between which the islands’ ferries shuttle. Public sculptures and pavilions by stalwart artists such as Yayoi Kusama and Olafur Eliasson now pepper the islands. This edition – the first since the COVID – pandemic, sees new works by an eclectic list of over 200 international artists, including Chiharu Shiota, Jakkai Siributr, Kenji Yanobe, Jacob Dahlgren and RAQS Media Collective. This enormous undertaking is partly backed by education publisher and arts patron Benesse (formerly Fuketake Publishing), and current chairman of the Fukutake Foundation Hideaki Fukutake (the son of its founder), leading to the establishment of a growing number of permanent art venues on the islands. The latest of these, the Tadao Ando-designed Naoshima New Museum of Art, opens at the end of May, with an inaugural exhibition of works by including Chim↑Pom, Takashi Murakami and Do Ho Suh. J.J. Charlesworth

Open City Documentary Festival

Various venues, London, 6–11 May

The UK is home to an impressive range of festivals dedicated to nonfiction filmmaking, including the Berwick Film Festival in March and the Sheffield Doc Fest in June. Landing between the two is this month’s Open City Documentary Festival, programmed by the anthropology department of University College London. Opening its fifteenth edition is the UK premiere at the Barbican of Siticulosa (2025) by British artist Maeve Brennan, in which she explores the southern Italian landscape where dominantly dry arid conditions allow for the appearance of crop marks to indicate the presence of archeological sites beneath – a continuation of her ongoing investigation into the largely illicit international antiques market. Meanwhile at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, the autonomy of our digital lives is questioned by John Smith’s Unusual Red Cardigan (2011), in which an online marketplace listing for a VHS tape of his own film The Girl Chewing Gum (1976) leads him to become fascinated by the anonymous seller. Two debut films stand out at this year’s festival. Armenian director Armand Yervant Tufenkian’s In the Manner of Smoke (2025) reflects upon the Californian wildfires, combining webcam imagery with footage of a contemporary landscape painter in London as he meticulously reproduces scenes from these surveillance images, as pixel merges into pigment. While Kouté Vwa (Listen to the Voices) (2024) by French-born filmmaker Maxime Jean-Baptiste, combines scripted scenes with archival material in French Guiana to present a portrait of a murdered son whose absence throughout the film is increasingly palpable. If there is a unifying thread between the multifarious screenings, it is that they expand the notion of what a documentary can be. Louise Benson