How are Brazilian artists with African heritage using a new visual vocabulary to make space for a more fecund relationship with the continent?

In 2022, Rio de Janeiro’s Museum of Art put out a call for works on and about important Black figures in Brazil for an iteration of the exhibition Enciclopédia Negra (Black Encyclopaedia). The São Paulo-based artist Larissa De Souza responded. Among other works, she submitted Nã Agontime (2022), an acrylic and mica pearl portrait of a handsome Black woman in a white blouse. The figure’s hairstyle is decidedly African, with long threaded spikes. Lavish jewellery adorns her neck and ears. She radiates a quiet dignity while her fervent eyes and tribal marks suggest a deep well of strength. The oval resin frame is studded with rocks, broken tiles, seashells, plastic combs and other ephemera that De Souza has referred to in interviews as amulets. The retratos pintados (painted portraits) style of northeast Brazil, in which plain black-and-white family portraits were beautified with colour, fancy clothing and jewellery, was a nod to the artist’s family roots in the area. The choice of the figure, Na Agontimé, is a nod to her African ancestry. Na Agontimé, an eighteenth-century wife of King Agonglo of Dahomey, was sold into slavery in Brazil. In São Luis, on the north coast of the country, where she is believed to have settled, she is credited with the founding the Casa das Minas temple, home of the Afrobrazilian religious practice of Tambor de Mina.

It is no secret that the link between Africa and Brazil is soaked in the blood of colonialism and the trade of human beings. Most people enslaved in Africa during the Atlantic Slave trade ended up in Brazil. And there they remained in chains longer than anywhere else in the Americas. But to stop there is to miss the deeper, life-affirming innovations that have come from the syncretism of languages, cosmologies, ways of being and even dreams that link people on both sides of the Atlantic. In the last decade, Afrobrazilian artists in particular have been taking up these elements of connection to make sense of the more violent histories; through art, the facts, symbols, stories, hunches, suspicions, whispers of this connection are braided more solidly together. In their incorporation of Kimbundu and Yoruba, Sankofa symbols and Orixa iconographies, Afrobrazilian artist are also expanding a shared imaginative geography, where Africa is brought along on explorations of the human spirit. While last year the 35th São Paulo Biennial, Choreographies of the Impossible, historic for being the first curated by a majority-Black team, toured in Luanda.

In some ways, the recent developments are a logical conclusion of a series of reflections begun in 1988. This is when the country marked a century of the abolition of slavery and Black activists begun a push for an open and frank engagement with the country’s more sordid histories. Two decades later, an Afrobrazilian museum would be opened in São Paulo. And in 2018 the Ooni of Ife, spiritual leader of the Yoruba people in Nigeria, would visit Salvador, the largest Black city outside of Africa and a centre of various Afrobrazilian religions keeping alive Yoruba traditions of religion and culture. Today Brazilian artists like De Souza, Jaime Lauriano and Aline Motta, with both their physical presence on the African continent, and increased engagement with its visual vocabulary as a key element of their work, forge space for a more fecund relationship with the continent.

“If belonging is a fiction,” Aline Motta asks in the voiceover narration of her video (Other) Foundations (2017-2019) , “can I point a mirror at Nigeria and see Brazil?” Motta, who has spent time in Sierra Leone and Nigeria, is among the artists whose work is in Angola as part of the Biennial. “Across the ocean,” she continues, “one points a finger to the other and asks: Is that really you? Why did it take you so long?” Motta’s work has at turns posed and attempted to answer this question. (Other) Foundations, along with Bridges over the Abyss (2017) and If the Sea had Balconies (2017) form a trilogy of videos doing the work of ancestral investigation, opening up new possibilities for kinship across the Atlantic.

Reversing the sail back to the African continent, Motta’s projects use archival research, photographs, oral history and field reporting, bringing them together on film and moving images. In (Other) Foundations, Motta spent time with the Egun community in Lagos, largely made up of migrants from Benin. The community is a coastal one, with some houses on stilts. The camera records various scenes on the water and plays with the namings of various locations on both sides of the Atlantic – Lagos (lakes) in Nigeria, Cachoeira (waterfall) in Brazil, and Rio (river) in both countries. This visual call-and-response is reiterated by people holding up mirrors in the respective locations and pointing them across the waters. Its echoes, overlaps and exchanges are captured throughout the film: in the all-white robes of religious practitioners in both countries, and in the shared sounds of their incantations, soft singing and musical instruments – talking drums, wind chimes and cowbells.

Motta and people in the community appear at ease with each other. One metaphoric scene depicts a Brazilian birth certificate, printed on fabric, hanging on a clothesline alongside the cloth wraps and skirts of women in the community. But negotiating belonging is always a complicated process. “Sometimes we manage to return to whence we came,” Motta says in the voiceover, “but, in this journey we find out that the house where you lived was demolished. And your place is a nondescript vacant lot.” Motta is referred to as Oyinbo (white), by the little Egun children. Black in Brazil and White in Africa, she wonders if they don’t know that no one became white in Brazil out of love.

The journey towards erasing the amnesia and reforging a familial relationship to the continent requires reckoning with the violence of the encounter that formed the links in the first place. The artist Jaime Lauriano works to revise national origin myths and recognise that, as he’s put it in a previous interview, “the construction of Brazil, the invention of Brazil, was through violence and the deportation of African people to work as slaves in Brazil.” For decades the myth of Brazil as a harmonious racial democracy conspired to justify the absence of Black faces and story in the popular imagination. Lauriano took part in the 2015 edition of the biennial Bamako Encounters, and credits his time there and in Morocco with prompting a rethinking of Africa and a curiosity about the nature of the enduring link between Brazil and the continent.

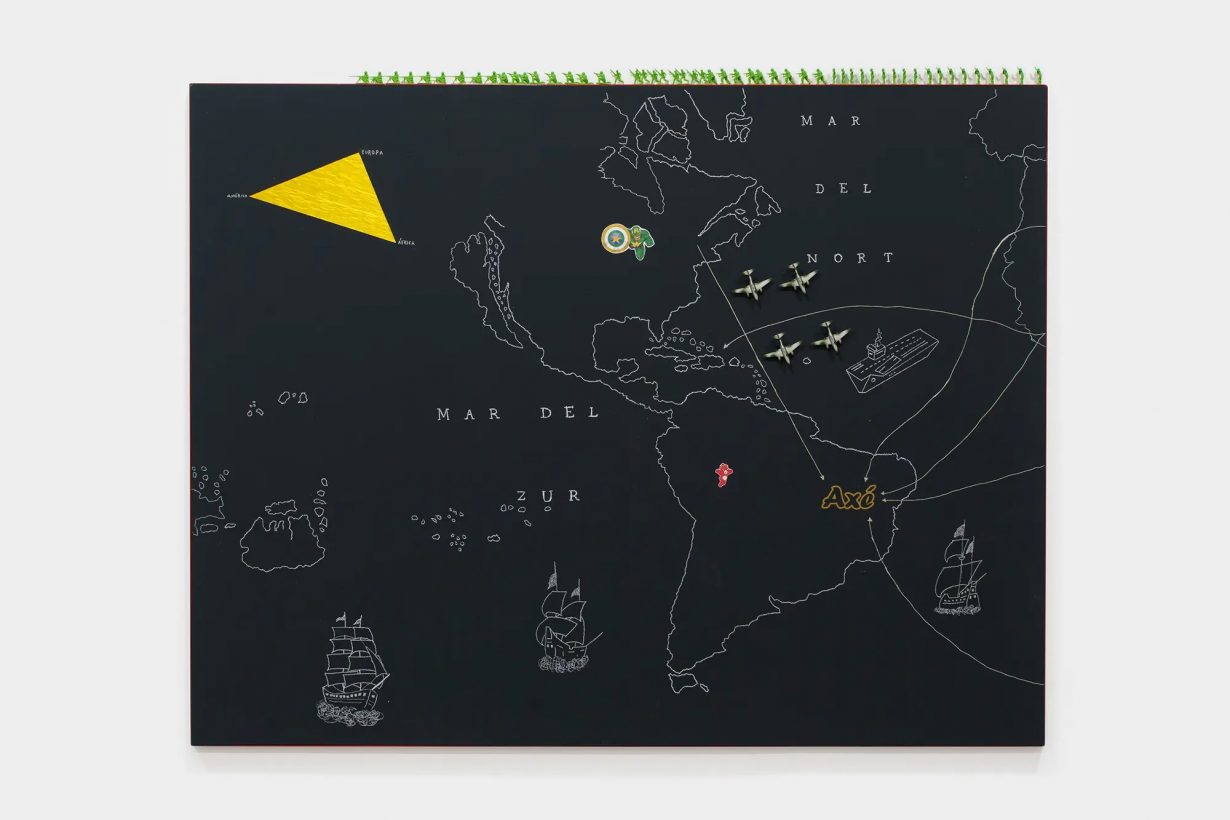

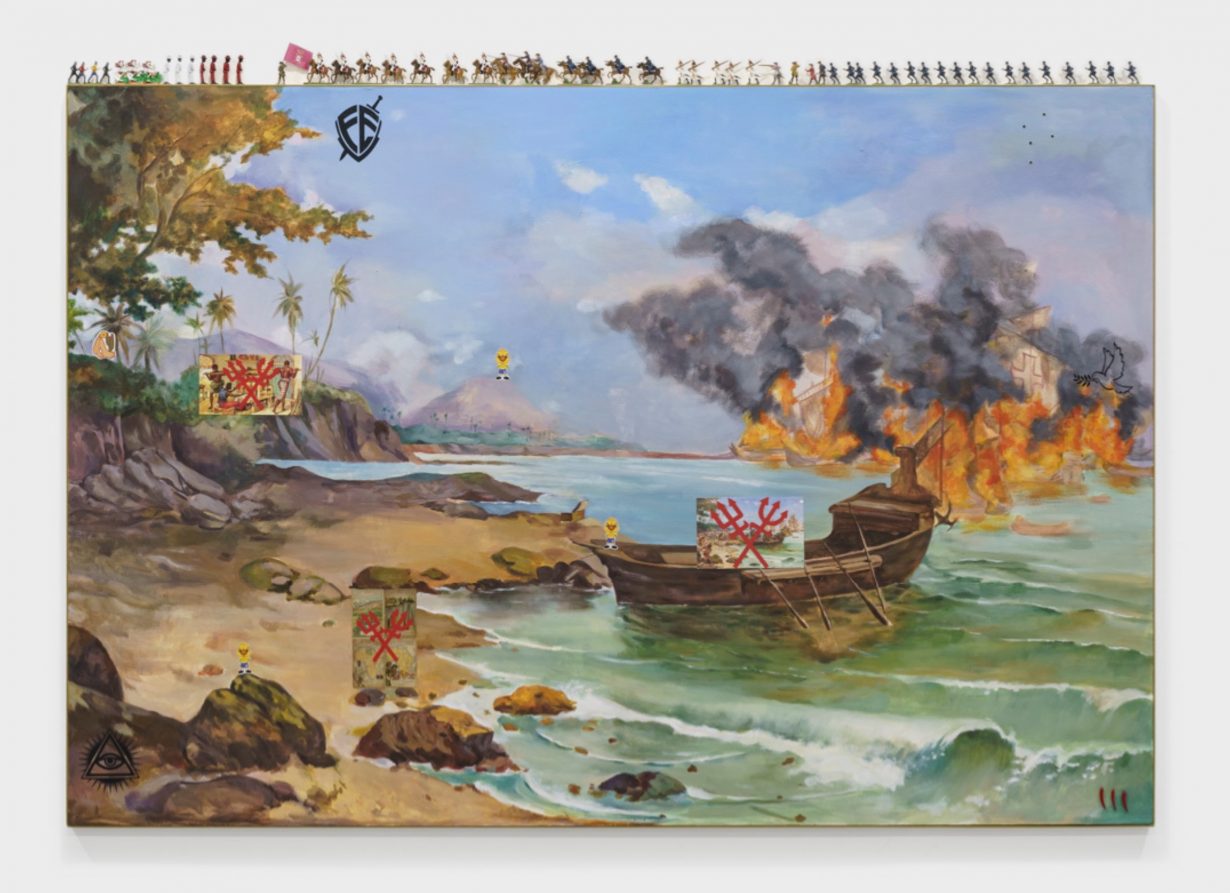

In his paintings, Lauriano revises maps (treating them as evidence of an early crime scene) and state-produced images to push back on what was left out and highlight what has been overlooked. In a work like Terra Brasilis: Invasao, Etnocídio e Apropriação Cultural (2015) he draws a version of the country’s map, depicting native indigenous people on the land, and the invading caravels and ships. He employs Pemba Chalk – typically used to summon spirits in Afrobrazilian religious rites – on black cotton. There are no romantic notions of motherland and patriotism here. The use of words like ethnocide, invasion, cultural appropriation and racial democracy, written in black and white on the cloth alongside the imagery, trenchantly demand a more sophisticated association between the imagery affiliated with the country’s founding and its brutal history. In other works, such as Invasão de Pedro Álvares Cabral em Porto Seguro em 1500 (2023), he takes academic paintings that romanticise the colonisation of the territory and adds imagery from Afrobrazilian religions like the Trident of Exu and the axe of Shango.

Lauriano is an author and organiser, along with the historian Flávio Gomes and anthropologist Lilia Moritz Schwarcz, of the Enciclopédia Negra. A project begun in 2016, it includes a book with over five hundred entries on individuals and a series of exhibitions (such as that in the Rio Art Museum in 2022, which opened in São Paulo and has since toured to Lisbon and Porto) with hundreds of works of arts. Art, notes Lauriano, offers “ways to tell stories other than the official story”. It recalls Motta’s assertion in her 2023 essay ‘Water is a Time Machine’, that ‘if there is a constellation of diasporic experiences, reconstituting territory is the same as reconstituting the self. Fragmentation becomes methodology and creative drive.’ In the encyclopaedia, the biographies of ordinary Black people who remain alive in rural oral histories and whose stories are passed down sit next to more prominent Afrobrazilians like Dandara dos Palmares, and Tereza de Benguela, leaders of independent Quilombo (maroon) communities in the 17th and 18th centuries respectively. Those for whom there is no visual record are given a visual portrait imagined by contemporary artists.

In the Americas, the image of Africa was for a long time that of a backwards continent, a place stuck in an evolutionary past; being labelled African was an insult. Decades worth of work has gone into challenging this condemnation of Blackness. Still, the choice of Afrobrazilian artists to insist on the connection and to keep the ancestry alive is an act of defiance. It is also a generative one. The Akan concept of Sankofa – to go back and get something from the past, in order to move forward – is often invoked in diasporic engagement with Africa. The routes between Rio, Bahia, Recife, Ouidah, Elmina, Benguela, Luanda, Sao Tome, Lagos and Goree appear more active than ever before, dotted with black footprints. In their work, these artists affirm that the links were never broken. They were always there. As De Souza, who has an exhibition of new work opening in Sao Paulo’s Simōes de Assis gallery in January, said in a recent interview, the task that remains for artists on both sides is to think ‘with the past’.

Anakwa Dwamena is a writer based in New York and Accra