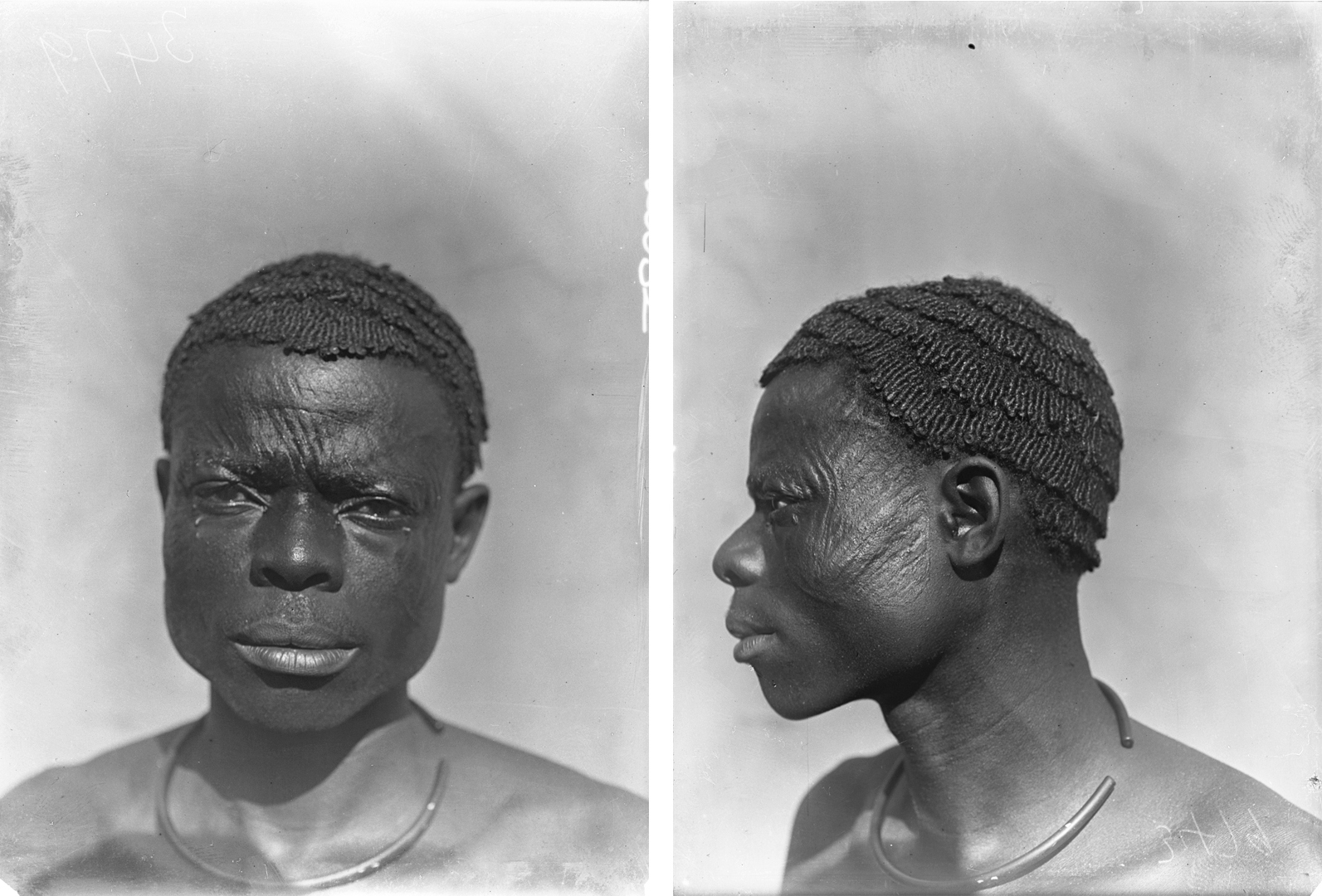

‘He has been selected at random from a group of men: for the precision of his features, the finery of his scars, the undulance of his chin’

Seen front-on and in profile, his look is intense in both photographs. Rows of woven hair, arrayed like shingles of a roof. A single piece of metal circles his neckline, the only ornament on his otherwise bare torso. His face, however, bears scars as intricate as birthmarks, etched into his person. In the front-facing photograph, as he looks beyond the camera, he seems cooperative, but also irritable. We can imagine this.

He has been selected at random from a group of men: for the precision of his features, the finery of his scars, the undulance of his chin. He is asked to remain just so, not to move an inch, not to turn any further to the right. He is marked out as ‘special’ for the purpose of the photograph. But not for anything else. He knows this.

He knows, too, he might not be designated a participant beyond this pose, this moment of being told to hold still. Or if he doesn’t know it, he’ll know it months or years after, when he tells his friends of the presumptuous stranger who didn’t even bother to give his name.

Maybe then, when he tells of it later, this man, whose name is given in the archive as Nwobu, will find it funny. A chuckle of amazement at being studied for features as congenital as the bulge of his nose or the crumple of his forehead, features that marks him as belonging to an unbroken line of faces.

Nwobu’s diptych appears on the website of a project entitled ‘Museum Affordances’, which reengages with the objects, photographs, sound recordings, botanical specimens and fieldnotes assembled during fieldwork in Southern Nigeria and Sierra Leone by Northcote W. Thomas, a British anthropologist of the colonial era. ‘What actions do they make possible?’ asks the project team on the ‘About’ page of the website, of the items gathered by Thomas. It’s a question that has spurred my appraisal, my attempt to be acquainted with an archival photograph from the region of Nigeria I’m from.

Nwobu might have been a child or an adult when he received the ichi marks on both sides of his face and forehead. This is how: the ichi specialist, travelling with two assistants, arrived at his house. One assistant carries a bag of tools, containing a knife and herbs. Then he prepares the mat and wooden headrest against which Nwobu is to lie for the marking. The other assistant is there to hold down Nwobu’s legs while the knife is worked around his temple. The specialist begins. Nwobu’s wife – or his mother, depending on his age – is there too, passing him a piece of fish to eat, to help with the pain. And singing in Igbo: Eee, ahh. You talking up and down, allow me to do my ichi marking. I will travel to places and be widely known. Eee, ahh. You cut and sharpen the knife; are you cutting beef?

‘If he moves or shakes, he is considered to be disgraced,’ writes Thomas, who took Nwobu’s portraits in 1911. When the specialist is finished, the bruised Nwobu is left to one of the assistants, who cleans the cuts with warm water and rubs in the herbs. ‘When he is properly healed he goes to the market and dances; some months after he takes a roasted crab to market and eats it there,’ the anthropologist continues.

On the website where I found Nwobu’s photographs, I note a portrait of Thomas – the first trained anthropologist to be appointed to the post of ‘Government Anthropologist’ by the British Colonial Office – taken during one of his three tours to Nigeria, in which his uniformed frame is centred, his eyes obscured by the shadow of a pith helmet. I contrast it with that of bare-chested Nwobu. One photograph is a snapshot documenting a journey, the other a careful anthropometric record.

I am most interested in afterlives. The extent of the anthropologist’s toil is impressive: 7,000 quarter-plate glass negatives survive Thomas, as well as multivolume reports. And I cannot dismiss the need these photographs crystallise: a need to know a time and place otherwise inaccessible to me. The inescapable shadow of British colonialism cast over the many institutions across which Thomas’s ethnographic archive has been dispersed: the University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, the British Library Sound Archive, the Pitt Rivers Museum, the Royal Anthropological Institute, the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, the UK National Archives and the National Museum in Lagos.

History as biography: it is this possibility I attend to, studying Nwobu’s gravitas. The people of Amansea, where he’s from, could either take ichi marks as children or as adults: the former if the child belonged to a rich family; the latter when a man acquired wealth. I cannot immediately tell if he was scarified as a child or as an adult. And I cannot tell this because it is hard to ascertain if the sternness of his gaze recalls the impudence of youth or disillusionment of middle age. The signals are mixed: the hairless chin might mark him younger, but his weathered temple points to a timeworn face.

I allow this disjuncture, this opening to the unknown. Only Nwobu can testify to what it feels like to be propped as a ‘physical type’, photographed as so. This is one chasmic silence between us, an exact measure of distance in the century since.

Emmanuel Iduma is a writer and photographer. His works include the travelogue A Stranger’s Pose (2018) and a forthcoming memoir on the aftermath of the Nigerian Civil War