As museums and galleries across the US add their voices to a growing tide of protest, more critical reflection and less tokenism is required

Another gruesome image seared into public memory. It is impossible to gauge how recent uprisings and outpourings of horror and outrage over the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis on 25 May will impact American society. Amid a global pandemic, thousands of people have tenaciously taken over the streets across many US cities. But whether current protests in the US against police brutality represent a tipping point is uncertain. Of course, coming from Britain, I’m all too aware of police brutality against black people; the British public is still to be apprised of events surrounding Mark Duggan’s extrajudicial killing in 2011, which sparked the England riots that year.

In the US, with a bellicose White House Administration found wanting, justice and progress are by no means guaranteed. America has been here before. Uprisings in Ferguson in 2014 and in Los Angeles in 1992 and in 1965 were emphatic responses to police violence. Today, America appears no closer to true racial equality than it was when the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed.

American society has proven itself capable of maintaining in both sophisticated and brutal ways a most emphatic form of race-based social distancing. Whilst physical forms of social distancing have become part of a ‘new normal’ since COVID-19, de facto racialised forms of social distancing – in housing, jobs, education and the judicial system – have long been intrinsic to American society. Policies intended to instil equality, such as affirmative action, have been proven to be unfit for purpose, compounding rather than diminishing inequity.

But social distance is a useful metaphor to think about the relationships between American and African American art, and art institutions and African American art. The ‘art of social distance’ is anything but a ‘new normal’. It usefully describes underlying politics which continue to modulate, in spoken and unspoken ways, racial delineations in American art. How can these unprecedented times, the era of Black Lives Matter, influence the art of social distance?

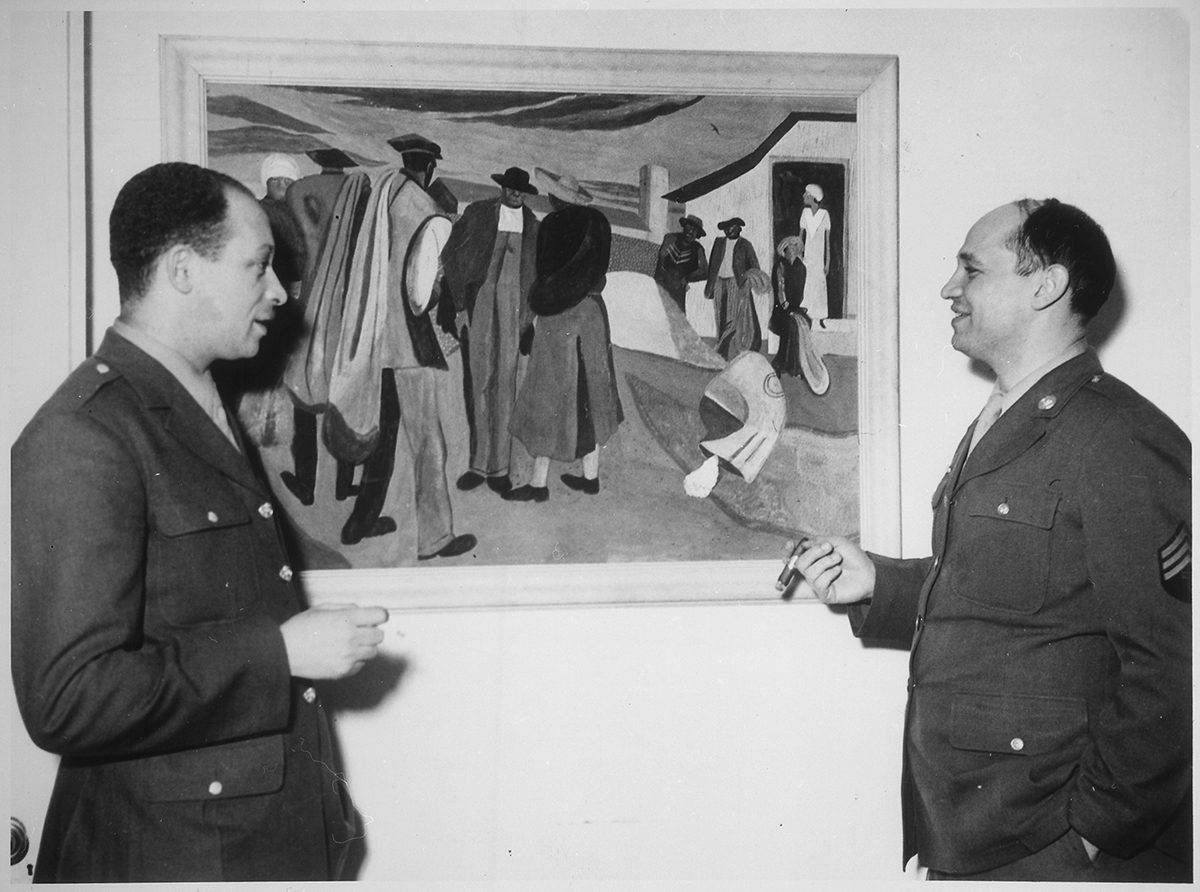

Seemingly every sector of American society has expressed anger and revulsion at the recent police murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor. From the car industry and technology firms to sportswear brands and record labels, statements of solidarity with African Americans have come thick and fast from corporate America. Likewise, museums and galleries across the US have added their voices to a growing tide of protest. The Guggenheim Museum, The Art Institute of Chicago, the Smithsonian Institution and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, among others, have spoken against ‘police brutality and institutional and structural racism’ and of how ‘museums cannot claim neutrality in addressing the horrific issues that have plagued our society for centuries’. Such sentiments bring to mind the artworld’s response to Dr Martin Luther King’s murder, such as MoMA’s rapidly-organized fundraising exhibition, In Honor of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (31 October – 3 November 1968), which brought together works by many leading artists of the time. These included legendary black artists such as Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence but also white artists such as Robert Rauschenberg and Mark Rothko.

For decades, corporate America has paid lip service to the fight against racial inequality. Time will tell if current outpourings of support will amount to more than platitudes. By contrast, major museums and galleries in the US have, over the past three decades or so, led the way in promoting and implementing various forms of inclusivity and diversity. The Whitney Museum of Art’s much-maligned Whitney Biennale in 1993 and Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art in 1994 mark this shift in the thinking of major institutions. Characterised at the time as a move towards multiculturalism, inclusivity was more identifiable through a triumvirate of race, gender and sexuality. Today, nothing typifies this ongoing practice in major museums more than the rise to prominence of African American art.

And yet there is a schism between the deference now bestowed on African American art and the harsh everyday realities of African American people: recognition, historical correction and progress on one hand, inertia, inequality and brutality on the other. There is little doubt that in terms of profile and visibility African American art is in a better place than thirty years ago. Its presence is noted not only in exhibitions both in the US and internationally but it is also more widely collected, written about and studied. In these troubling times, the institutional embrace of African American art contrasted with the martyrdom of black life carries even greater significance. This is nothing new. David Hammons’s Injustice Case (1970) or Elizabeth Catlett’s The Black Woman Speaks (1970), were made in and were the products of traumatic periods.

The art of social distance has historical roots. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, African American artists often sought refuge from American racism by travelling abroad. Equally, the wanton treatment of African American art in the postwar period by American art institutions bore an uncanny resemblance to the constitutional mantra of ‘separate but equal’. Modern Art in the United States: A selection from the Museum of Modern Art, New York, which toured to Tate Gallery in 1956, was one of many such exhibitions not to include an African American artist. The art of social distance remains fundamental not only to understanding the enduring racial bifurcation of American art but also more recent curatorial framings such as Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power.

Fittingly, MoMA’s webpage for its 2018 exhibition Charles White: A Retrospective opens with the words ‘Art must be an integral part of the struggle’. By no means a salve to the pressing problems of today, the work of African American art occupies an exceptionally important position in American history. Race politics have informed the reading of African American art, but in white American art history they are largely silent, though equally applicable. An all too rare exception to this was the exhibition Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties (at the Brooklyn Museum of Art in 2014), which co-curator Teresa A. Carbone noted ‘sought to reference legibly the dramatic cultural and political shifts at hand, including the heroic efforts and harrowing events of the Civil Rights Movement’. The show included a rare multi-racial line-up including Richard Avedon, Jim Dine, Larry Rivers, Norman Rockwell and James Rosenquist, Bearden, Catlett, Rauschenberg, Hammons and Melvin Edwards.

Over the past few days, many US museums have spoken forcefully, including the Art Institute of Chicago which described current events as a fight ‘against police brutality and institutional and structural racism’. Attempts to effectively de-militarize the policing of black neighbourhoods through defunding are a bold move. Whatever unfolds in the coming weeks, months and years in the US, the challenge for galleries and other institutions will be how they can be true to their words and continue to push back deep-seated racism be it inside or outside the institution. However presently, as much as it is a time for action and vocality, and as counter-intuitive as it might seem, ratcheting up equality policies, scrambling to diversify trustees and staffing will miss the point. More critical reflection and less tokenism is needed. As current events graphically illustrate, from the Civil Rights Act onwards, decades of laws, policies and initiatives have not only failed to diminish racial inequity but have normalised it in everyday life. At a time riven with uncertainty, when coronavirus and protests against police brutality have challenged conceptions of normality, art institutions must also more fully consider the real implications of a ‘new normal’ in an era of Black Lives Matter.

Richard Hylton is Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences Diversity Postdoctoral Fellow at University of Pittsburgh