One man’s persistence has brought Thailand’s rich comics tradition to light – now we need to connect its spirit of critique and independence to current times

Belgian comics scholar Nicolas Verstappen began sifting through Thai comics five years ago. Plenty of time, you would think, to discover if Thailand had a comics canon worthy of comparison to the totemic Anglo-American, French-Belgian and Japanese traditions. However, due to a lack of local knowledge and of archives predating the 1980s, the process proved slow going. Several years passed, during which he scoured markets, libraries, antiquarian bookstores and online groups without much luck, until, just before the scheduled completion of the book he was working on, published this month as The Art of Thai Comics, the breakthrough came. ‘My Tutankhamen’s tomb: more than a thousand comic strips, cut from 1930s newspapers and bound together, were found in boxes during the reordering of an attic,’ he writes with palpable relief. ‘There lay almost the complete comics production of Sawas Jutharop and Jamnong Rodari, with early works by Prayoon Chanyawongse and Tookkata.’

This anecdote bears repeating – without the rare examples of Thai comic strip mises-en-scènes these freshly unearthed finds provided, The Art of Thai Comics wouldn’t be as expansive and richly drawn an achievement. Some of these names are barely remembered in the Kingdom, let alone celebrated outside it – an injustice this large-format book, arranged chronologically into chapters on influential cartoonists, imprints and trends, and released in Thai and English editions, strives to correct.

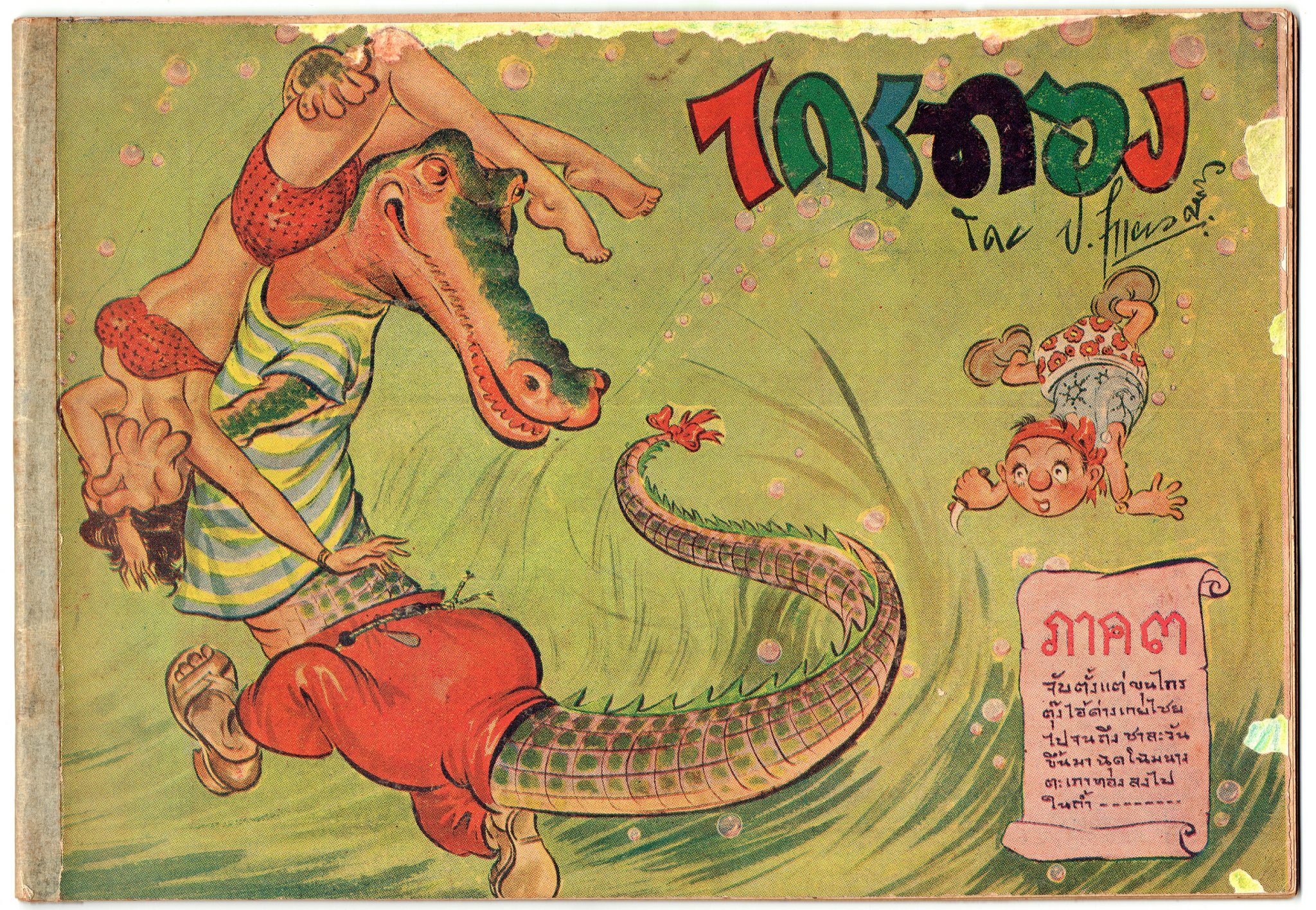

Drawing also upon interviews and national archives, Verstappen skilfully illuminates the chequered lives and turbulent social contexts of his subjects, both cartoonists and sketched characters alike. Take Sawas Jutharop, a Bangkok boy, born to a family of goldsmiths in 1911, who hit his creative stride just as Siam was transitioning from absolute to constitutional monarchy in 1932. His work is emblematic of how comic artists of the time, cowed by new press laws, turned their backs on satirical strips lampooning nobility and officials, and turned instead to long-form adaptations of Thai epic poems, albeit ones that often chimed with current events. Verstappen illustrates these biographical tidbits with fine examples of Sawas’s strips, from the serialised adventures of an investigative journalist in 1932’s Nak Suep Khao through to the early appearances of alter-ego Khun Muen, the Popeye- inspired prankster who appeared in his adaptions of classic chakchak wongwong folktales about princely heroes.

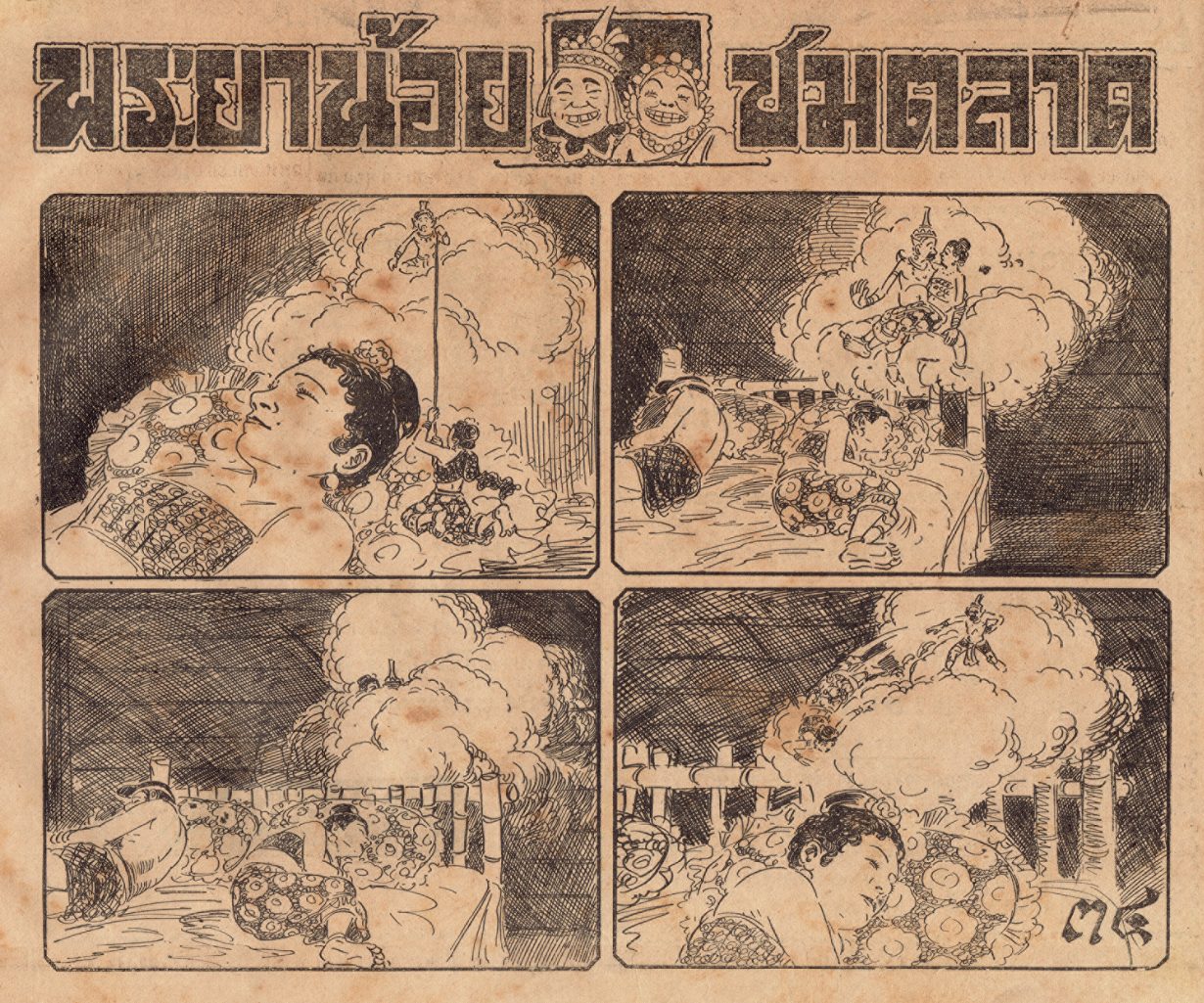

Also emerging during the 1930s was the enigmatic Jamnong Rodari, described here as ‘the first Siamese cartoonist to bring naturalistic representation to the artform’. He was also, Verstappen adds, ‘the most consummate’ of the era, on account of his loosely pen-drawn and playfully anachronistic narratives rendered with ‘a remarkable sense of rhythm, composition and design in outstanding sequences – sometimes silent, expressionist or oneiric’. Such effusive praise is entirely warranted judging by the accompanying strips, among them a Harold Lloyd- style slapstick scene set in a then modern-day Bangkok, and a fey dreamscene, circa 1934, from vaudeville folktale Phraya Noi Chom Talad.

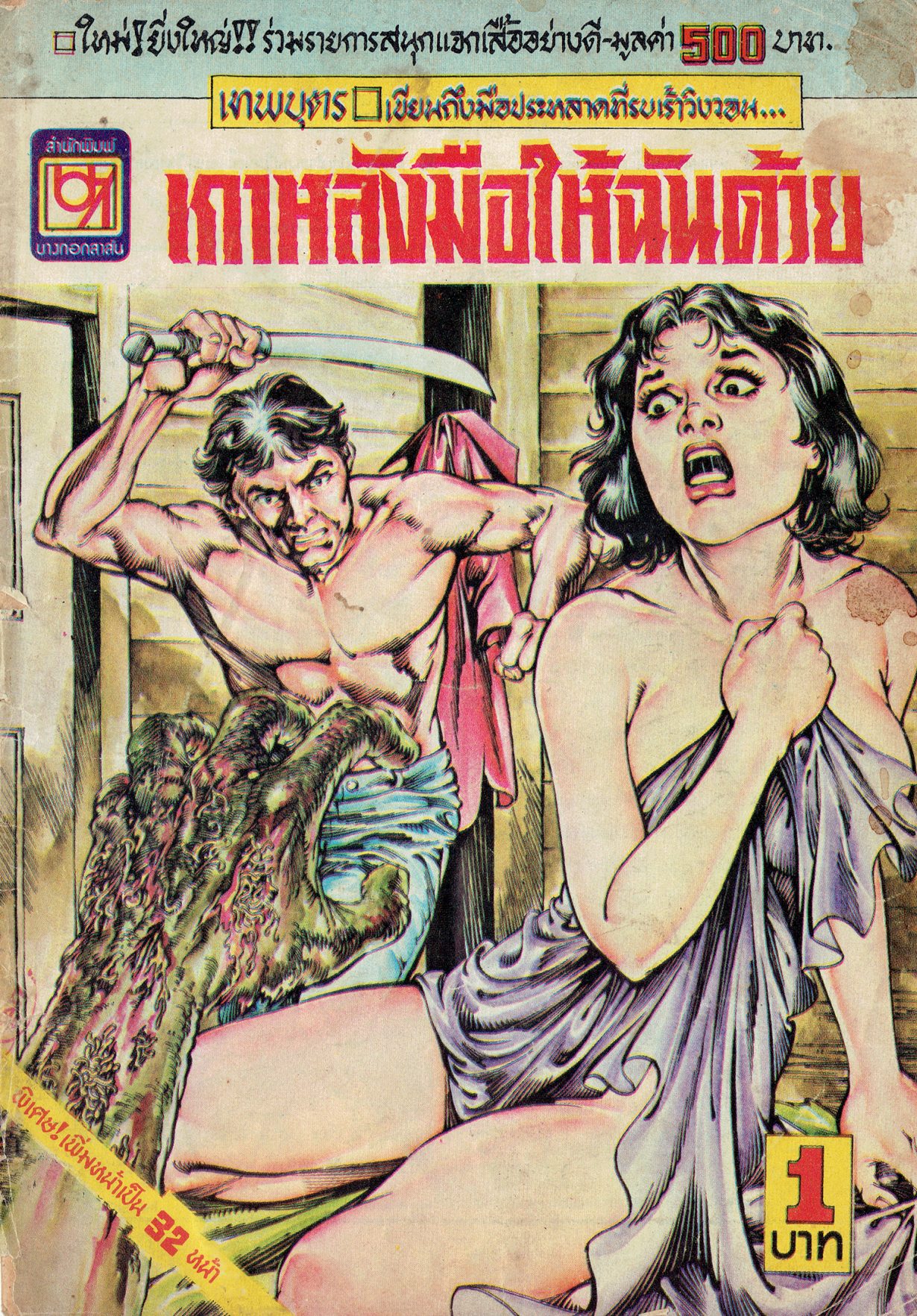

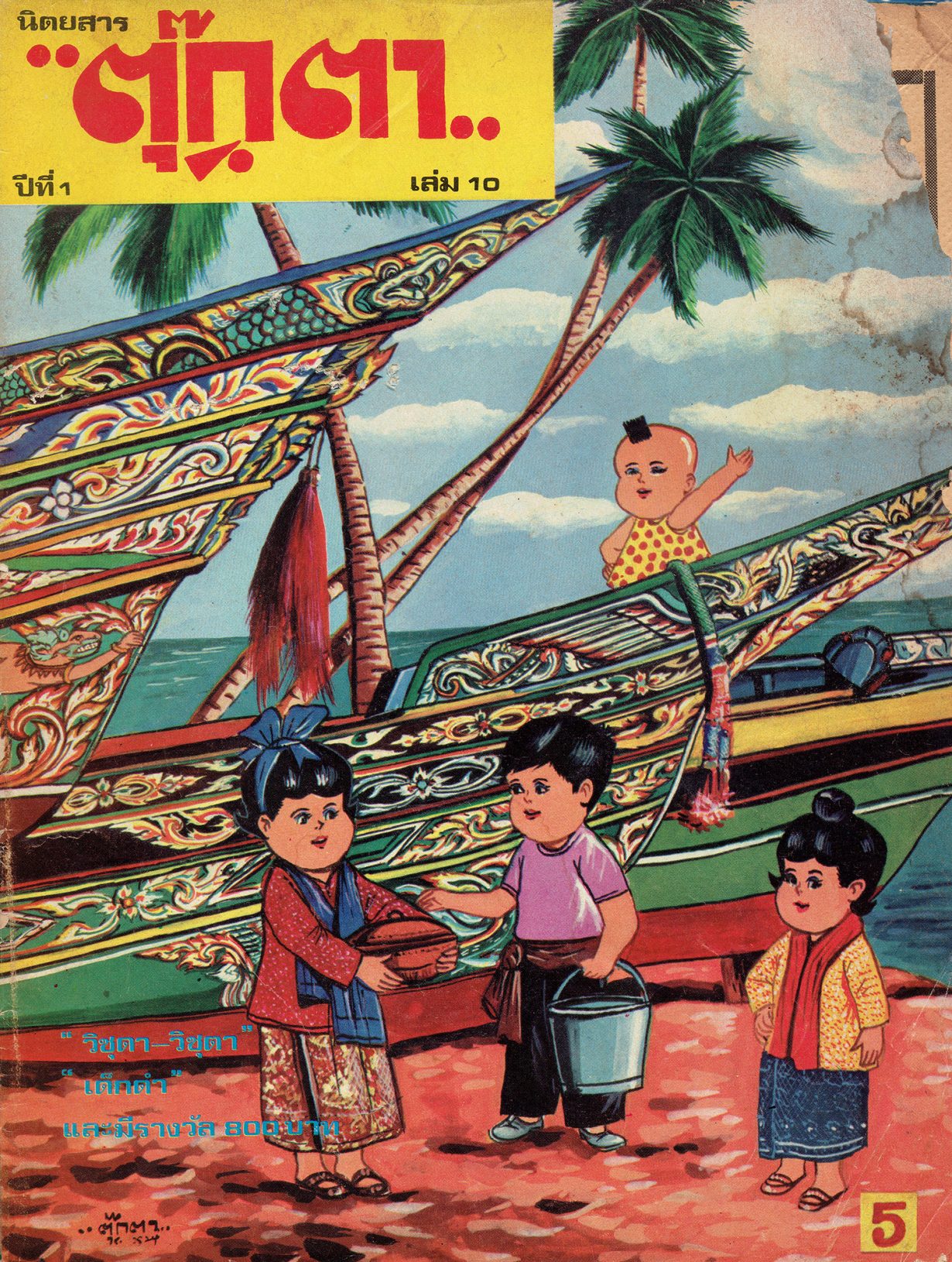

Over 30 cartoonists and their creations are profiled in this assiduous manner, from titans such as midcentury master-of-shade Hem Vejakorn to lesser-knowns such as chronicler-of-the-underdog Triam Chachumporn, from dashing folk princes with Elvis pompadours to phi krasue (nocturnal female ghosts) trailing blood and viscera. On

the way, Verstappen parses changing reading tastes (mass circulation one-baht comics, graphic novels, horror and sci-fi, the manga wave), disruptive shifts (wars, imports, trauma) and even the occasional melee between cartoonists and the ruling powers. In 1972 the leading political cartoonist of the day, Prayoon Chanyawongse, responds to military censorship by drawing his most famous character with his mouth sewn shut. In 1973 a group of students sow popular discontent by producing a widely popular comic pamphlet about animal poaching. In 1976 another political cartoonist, Chai Rachawat, has his series banned by a dictatorial new regime on the grounds that it contains messages to communist insurgents. And in 2021 antijunta satirical strips drawn by anonymous artists gain thousands, if not millions, of likes on social networks.

If I have a bone to pick with The Art of Thai Comics, it’s this: while it broaches the moments when the Kingdom’s artists explored personal and at times boldly political themes, it neglects to meaningfully connect the dots between them, to explore their relationship with Thailand’s current vexed and vitriol-filled moment. This is ostensibly because Verstappen has opted to focus solely on printed materials and the period 1907–2007: a century that begins with the first known Thai multipanel comic and ends with the peak of the Thai independent comics scene. In doing so, he conveniently avoids having to give a newer, bona fide phenomenon worthy of sustained attention – online comics – more than a cursory mention. Given the clear lineage that online comics such as Kai Maew and Jod 8riew – unfettered and cathartic expressions of political disenfranchisement and alienation – share with the pugnacious social commentary of Siam’s 1930s proto-comic strips, not to mention the angst-filled horror and gore titles of the late 1970s and early 1980s, this feels like a missed opportunity (or the makings of a followup, perhaps?).

But to nitpick in this manner is to fling paper darts at a rippling giant: Verstappen has crafted a work of huge breadth, accessible scholarship and real sociohistorical importance. Blending erudite readings of drawing styles with careful dissections of narrative traditions, applying detective work and high-minded analysis to a popular medium often dismissed as coarse and lowbrow, he skilfully charts the myriad ways Thai cartoonists have, in that spirit of unconscious eclecticism often said to embody ‘Thainess’, artfully borrowed and synthesised local and foreign influences: Jataka tales, likay theatre, Javanese shadow puppets, Popeye’s bulging biceps, among untold others. With each new page, a different member of the Thai comic pantheon is boldly redrawn – many long lost due to the ravages of paper and memory – and another part of the unique social scaffolding on which they stand is uncovered.

The Art of Thai Comics, by Nicolas Verstappen, is published by River Books