Solidarity today is at once among the most urgent political projects and among the least likely to succeed

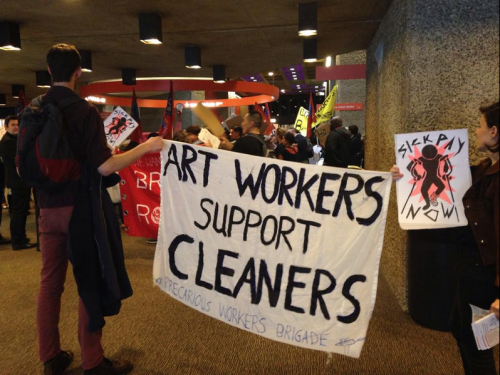

Artists do not have a great reputation for solidarity. The mythic image of the isolated individual in the studio contrasts perfectly with the tropes of solidarity: picketing strikers, antiwar marchers, the encampments of Greenham Common and Occupy. Recent theoretical and activist challenges to what American art historian Caroline Jones has characterised as the ‘romance of the studio’ have disclosed the scale and variety of interchanges necessary for the production and circulation of art – and the army of unheralded nonartist art workers involved; interchanges that have resulted in an extension of solidarity between artists and the art workforce more generally, as exemplified by the Precarious Workers Brigade, among others.

This is unusual. More typically, artists establish relations with non-artists without making appeals to solidarity. For instance, art’s ‘social turn’ during the 1990s was a project to socialise the artist through convivial or agonistic methods of audience participation, which fell short of establishing networks of solidarity. A conference at Tate Modern in February 2019, ‘Axis of Solidarity: Landmarks, Platforms, Futures’, looked at how artists can support solidarity movements. But what would it take for art itself to become an infrastructure of solidarity?

The age of rightwing populisms that has set people against one another, and the age of multiple overlapping privileges and microaggressions, is not the epoch of solidarity. If solidarity is needed more than ever during the period of its crisis, solidarity today is at once among the most urgent political projects and among the least likely to succeed. The current crisis of solidarity has been articulated best by those critical movements that emerged after 1968 and that shattered the anti-capitalist hegemony of a seemingly unified working class. Solidarity, it seemed at the time, was little more than a cover story for discipline within the established workers movement. Identity appeared to some as the only basis for solidarity and therefore solidarity across identities was so often curtailed or blocked. However, it is wrong to blame the absence of solidarity today on identity politics alone. The institutions, ways of life and resources of the workers movement collapsed under the weight of the rightwing backlash against the postwar settlement, not because a wider spectrum of voices made themselves heard.

It is more difficult to imagine art as a site of solidarity when political solidarities are in retreat and the political theory of solidarity has been out of favour for so long. The liberal tradition has always scrupulously administered a blindspot towards solidarity. Richard Rorty’s 1989 study, Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, with its ‘liberal utopia’ of contingent solidarity, or solidarity without commonality, is as close as it gets. Solidarity is strongest, he claimed, ‘when those with whom solidarity is expressed are thought of as ‘one of us’, where ‘us’ means something smaller and more local than the human race. Just over a decade later, even this half-baked definition of solidarity appeared starry-eyed. In his final contribution to the collaborative book Contingency, Hegemony, Universality (2000) Slavoj Žižek, in dialogue with Judith Butler and Ernesto Laclau, sardonically characterised the difference between the rightwing intellectual and its leftwing counterpart in the years immediately after the collapse of communism in terms of their attitude to solidarity. The former, he said, ‘rejected all forms of social solidarity as counterproductive sentimentalism’, whereas the latter was a ‘deconstructionist cultural critic’ who subverted the existing order, including ideas about solidarity, and therefore ‘served as a supplement’ to the project of the right.

But seriously, it is fair to say that while neoconservatism and neoliberalism set about patiently to dismantle the legal, economic and cultural prerequisites of leftwing solidarity (employment rights, state pensions, unemployment and sick pay, trade unions, housing regulations, the welfare state and so on), political theorists on the left consciously displaced the established discourses of solidarity with more philosophically robust discussions of hegemony, identity, placed-based politics, community, the counter-public sphere, agonism and intersectionality, among other things. Critics can be suspicious of solidarity as a method for establishing allegiances to power. Judith Butler, for instance, observed how the demand for solidarity within political movements has been perceived as the demand to sacrifice oneself for the sake of the group.

The political confrontation between identity politics and a politics of solidarity were laid out by bell hooks in her pathbreaking 1986 essay ‘Sisterhood: Political Solidarity between Women’. Here hooks writes, ‘black women were quick to react to the feminist call for Sisterhood by pointing to the contradiction – that we should join with women who exploit us to help liberate them. The call for Sisterhood was heard by many black women as a plea for help and support for a movement that did not address us.’ If the problem with sisterhood exposed by hooks corresponds exactly to the critique of solidarity from identity politics, for hooks the problem was a lack of solidarity in the feminist movement. ‘Women do not need to eradicate difference to feel solidarity,’ she said, adding, ‘Solidarity is not the same as support. To experience solidarity, we must have a community of interests, shared beliefs and goals around which to unite, to build Sisterhood. Support can be occasional. It can be given and just as easily withdrawn; Solidarity requires sustained, ongoing commitment.’

Although hooks builds a powerful case for the political merits of solidarity, it is Jodi Dean who has done most to theorise solidarity, in her recently republished book Solidarity of Strangers (1996). Dean distinguishes between different political conceptions of solidarity, identifying three main types: ‘conventional solidarity’, which arises out of common interests; ‘affectional solidarity’, which is a narrower form of support based on feelings of mutual care and concern limited to friends; and ‘reflective solidarity’, to name that kind of solidarity that is formed through discursive interconnections in which differences emerge through processes of recognition and response, discussion and questioning, and openness and accountability. Conventional and affective solidarities are inherently exclusive. Affective solidarities do not extend beyond an intimate network, while conventional solidarities ‘respond to the value pluralism of contemporary multicultural societies by increasing the demands made on group members, by rigidifying identity categories’.

Dean’s concept of reflective solidarity is formulated precisely to overcome these difficulties. The principal difference between conventional solidarity and reflective solidarity for Dean turns on the function of dissent within a group. ‘In contrast to conventional solidarity in which dissent always carries with it the potential for disruption, reflective solidarity builds from ties created by dissent.’

Solidarity based on debate is harder to imagine than solidarity based on identity in this epoch of fragmented solidarities, conditional alliances and specified communities. Solidarity, we can say, has become narrower, not weaker, insofar as specific splintered social groups can obtain the highest intensity of solidarity but pose a threat to solidarity that might be formed not only across divisions within a specific group but also between such groupings. Rather than solidarity being something that can be assumed between people suffering from the same system of prejudice or exploitation, it needs to be built through common practices. This is why Dean stresses that ‘solidarity itself has to be understood as an accomplishment’. Here, then, is the fully baked definition of solidarity.

When groups, including art organisations, assert the primacy of practical action over theory, they are, in part at least, prejudicing their style of solidarity in favour of assumed shared interests and blocking the possibility of developing and extending solidarity through disagreement and dissent. However, while the differences between affectional, conventional and reflective solidarity are conceptually enriching, there is no reason to assume that they are practically incommensurable. The point is not to assert that there is only one true social form of solidarity but to overcome the misconception that solidarity is the politics of a narrow, exclusive club identity. Different groups, organisations and institutions foster different combinations of congeniality, cooperation and critique. This sense of the interweaving of modes of solidarity was missing from the debates on art’s social turn, which treated conviviality, agonism and conversation as rival models of sociality rather than components of an integrated, dynamic and expansive form of solidarity. And this goes some way to explaining why the 1990s debates on the social turn now appear so dated and diluted.

All politically engaged art or political engagements within art that have emerged in the last decade have shifted the pattern of organisation in art away from sociality towards solidarity. Ecological activism in art has also encouraged forms of solidarity rather than sociality. Liberate Tate was successful in breaking up the partnership between Tate and BP because it facilitated collective acts of dissent that converted shared convictions into palpable expressions of solidarity. In other words, Liberate Tate was an infrastructure of solidarity. Campaigns for the decolonisation of art’s institutions and demands for reforms to alleviate the precarity of artists and art workers are best not when they call for differentiations between educated and unskilled workers but when they establish ongoing solidarities between them. This is why the ‘statement of solidarity’ of the Turner Prize nominees in 2019, which resulted in them sharing the award, was a glorious gesture of the intersectional recognition of the urgency of a range of political struggles even if its solidarity with others remained symbolic or unrealised.

The tendency to boycott museums and biennales, particularly since 2014, for instance, is driven by the solidarity of artists, critics, curators and others. Calls for solidarity and activism were combined, for instance, when over 100 artists and writers added their signatures to an open letter to selected artists to boycott Creative Time’s Living as Form exhibition in 2014 because one of its venues is an institution with a ‘central role in maintaining the unjust and illegal occupation of Palestine’. The boycott of the 19th Biennale of Sydney and Manifesta 10 were also based on a show of solidarity among participating artists. What’s more, these campaigns typically express or establish solidarities with migrants, prisoners, the victims of war and occupation, as well as expressing solidarity with broader struggles against racism, sexism, homophobia and colonialism. It is the viability of such solidarities that determine whether the art boycott is a technique for hoarding political agency by a minority of art professionals or a method for demonstrating that every political struggle must also be a cultural struggle.