Is contemporary art’s recent moral tide just a ‘moment’?

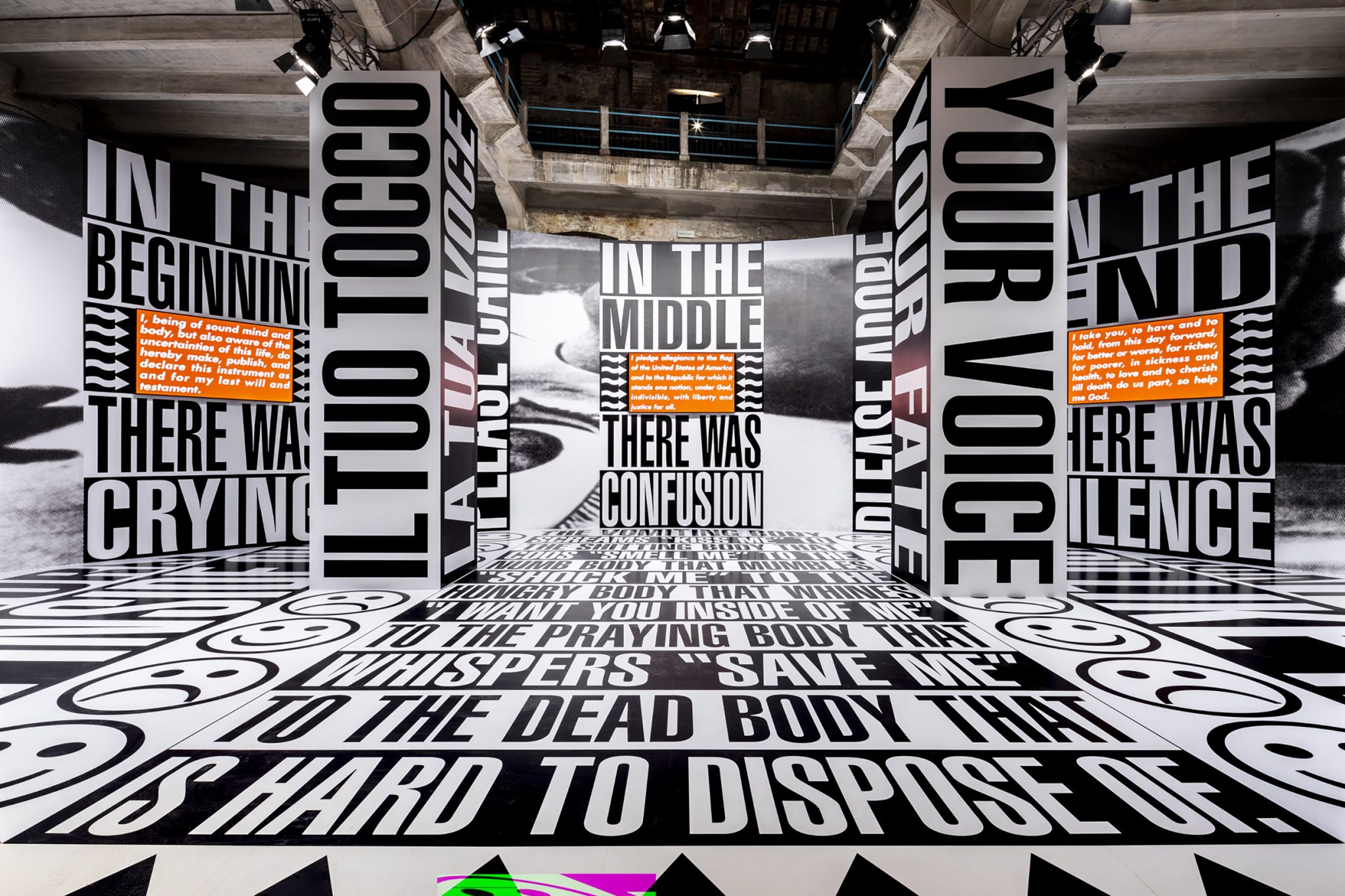

It’s not always easy to identify the prevailing trends in contemporary art: since the coexistence of Pop and Minimalism in the ‘60s and the subsequent advent of pluralism, art has tended to constitute a jostle of conflicting aesthetic and critical positions, the picture varying according to standpoint and taste. Of late, though, the landscape has seemed quite legible. If you’ve been visiting biennales or institutions and a fair swathe of forward-thinking commercial galleries, the art there is increasingly predicated on giving voice to the formerly underrepresented or trying to right former wrongs. Hence, to take a few recent examples, a Venice Biennale composed of 90 percent women artists, a Documenta full of collectives new to even seasoned Western art-watchers – and evidence, via the media shitstorm, of the pitfalls of decentralised curating – and museum shows that, when they do spotlight dead white males (Hogarth at Tate Britain, for example, or German ‘colonial’ modernists at Berlin’s Neuenationalgalerie), seek to pre-emptively point out said artists’ moral failings before the hanging jury of Twitter can do so. Also, and relatedly, living white male artists complaining, three beers in and off the record, that they’ll never get another show.

And then there’s the art market, which, though it now leans more towards women artists and artists of colour than it used to, still seems primarily enraptured by eye-pleasing painting in dialogue with familiar historical aesthetics – witness the popularity of, for example, Anna Weyant, Christina Quarles, Flora Yukhnovich – which points in turn to an audience less interested in being challenged than in easy pleasure, handholding, and maybe a quick profit. One can’t wholly blame said buyers, given the hurry of the auction houses to bundle art with any kind of luxury item in a kind of marvellous economic relativism, plus a phalanx of gallerists not too keen on wasting time educating new collectors towards knottier fare. Back in the museums and biennials, the much-needed shift in terms of who gets exhibited – and who decides who gets exhibited – is unthinkable without the righteous frustration and mobilising of social justice movements during the last decade or so or the hair-trigger mood of social media. Given the spotlight, finally, under-recognised artists are naturally airing their grievances. Meanwhile, the ‘haves’ dependent on structural inequality in the first place are, as usual, shopping for baubles and using the biennials to network – the painterly Surrealism that was a signature of this year’s Venice Biennale is looking like a smart investment.

Of course, this is a bit of a cartoon and there is art around, on show, that falls into neither of these camps – there are always exceptions, if you look – but the latter increasingly feels to fall outside of the larger, increasingly pronounced dualistic paradigm. If you complain, though, especially from a position of longstanding privilege, that amid all of this you’re not seeing enough of the art you want to see (whatever that is), that moralistic gatekeepers are running scared or legislating for you, that you’re now aesthetically stateless, then you’re on sketchy ground. Jerry Saltz, on social media a few months back, opined that ‘In our time when art about “good causes” is automatically called “good”, it feels like the anxieties of the critical-academic-curatorial-mercantile class is [sic] imposing the definitions of these things on artists & limiting art to being “responsible” according to its rules’, and I’m still pondering what I think about that. I see enough examples of, say, complexity – a core virtue of art, for me – not being sacrificed in socially conscious art, though it can be harder to see when the work is being instrumentalised by curators, framed as a consumable message. It is, at the very least, something to wrestle with, perhaps while looking a little harder for the art that you want to see, giving time to art that you think you don’t, and checking in often enough on the stuff that’s historically rung your cherries so that you remember why you got involved in the first place, which is healthy practice whatever else is going on.

What’s certain, amid all this, is that contemporary art doesn’t stand still. The last time vanguard art practice felt this urgently politicised and was given a substantial stage on which to perform was the early ‘90s – recall, for example, the controversial Whitney Biennial of 1993 – and identity politics was the focus until, somehow, it wasn’t. Artists of my acquaintance who have been lofted in part by the recent rising moral tide are already wondering out loud if this is, again, just a ‘moment’, a trend, and the artworld – and the clout-chasers within it, once clout is secured – will soon have lost interest, moved on to something else. Maybe: some commercial spaces, at least, have started to return to showing old white dudes, which felt almost unthinkable a year ago. Or possibly, given that increasing disparity and extremism (of wealth distribution, of public opinion) seems to be the trend, we’re set for a more pronounced version of the same: a contemporary art scene – or pair of scenes – set against a raging hellscape of contemporary reality, in which there’s no justification for either subtlety or non-profitability, in which he, or she, not busy yelling is busy buying. In the meantime, the binary landscape offers one conspicuous virtue. In pointing combinedly to inequality, anger, blissful ignorance and gilded pleasure-seeking, and a residual degree of hope that conditions can yet be improved, it shows us precisely where we’re at right now.