‘I do not intend to speak about; just speak nearby’ – the filmmaker’s positioning against the colonising gaze provides paths to solidarity today

I took a stroll down a residential street in Los Angeles, one of the most diverse cities in the world, and witnessed teenage boys of European descent speaking ‘fake Asian’, much to their own dumb amusement. It had already been another dire day in the headlines for the faltering USA: fires were in the hills; the virus was out of control; the government was out of control too. This sidewalk banter seemed to confirm the disintegration of the moral social fabric as well. The boys’ behaviour illustrated the casual racism that heralds the systemic racism that plagues the nation. What, I wondered, constituted behaviour or speech that would provide viable resistance to their cruel laughter and all it implies? Certainly my scolding would not suffice. Let’s be real. More thoughtful work is needed, which is why I found heart in the films of Trinh T. Minh-ha.

A general tactic for grasping Trinh’s cinema is supplied by the artist herself. The frequently quoted line from her first film, Reassemblage (1982), a study of women and rural life in Senegal, where she lived for three years while teaching at the National Conservatory of Music in Dakar, goes: “I do not intend to speak about; just speak nearby”. Trinh refers to her position as a visitor vis-à-vis the villagers she met and discloses her position as an un-authoritative narrator.

Trinh is now a professor at the Gender & Women’s Studies and Rhetoric departments at the University of California, Berkeley, but her influence on contemporary filmmaking is such that each Thursday this past July the Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, in San Francisco, used its YouTube channel to broadcast one of the Vietnamese theorist and filmmaker’s films as part of a yearlong project titled ‘Trinh T. Minh-ha is on our mind’.

dir Trinh T. Minh-ha, 108 min. Courtesy Trinh T. Minh-ha

At this juncture in living history, one might struggle to find urgency in these films. For some years the world has been afflicted by a post-truth regime, a cynical phenomenon that promotes speaking only of oneself and cares nothing for philosophical rigour as regards the elusive nature of truth. And for all of its influence in the literary and visual arts, deconstructionism – a prominent influence on the work – is not exactly au courant. The films are products of their eras, despite their timeless intentions, which begs the question: why do they endure?

Reassemblage, with its nonlinear construction and soliloquy, sets out many of the reasons why Trinh’s output remains the object of so much contemplation. It defies narrative conventions but contributes to the history of the documentary, with its conspicuous self-reflexivity leading many to label it an ‘antiethnographic’ film. Here, ‘anti-’ opposes the discipline of ethnography and its colonising gaze. The negative prefix indicates resistance to the status quo. We are not meant to conclude, however, that Trinh’s lens achieved radical objectivity. Rather, she upheld the gap between seer and seen by incorporating self-awareness into the very process of filmmaking: ‘speaking nearby’ is the creed of a conscientious interloper.

But what sets this apart from well-established doubts about film as a vehicle for pure truth? Trinh rejects the fiction/nonfiction binary – each, she recognises, contains aspects of its supposed opposite; both are dubious in their own right. In that dichotomy’s place she foregrounds doubt and situates the language of film in a deconstructive mode, allowing her to manifest the living complexity of those who populate her films yet leave them unscathed by ‘authoritative’ qualification.

Courtesy Trinh T. Minh-ha

Although Reassemblage was screened at Wattis outside of the framework of the film club, its thesis applied to the whole online programme, including The Fourth Dimension (2001), Trinh’s first digital film, which concerns time as she experienced it in Japan. Through layered images, text and sounds, the film registers the oscillation of tradition and progress that conjures a phantasmic Japanese culture situated somewhere between the protracted intervals of Noh theatre and the rushing speed of a bullet train. This temporal flexibility influences the film’s structure. In a brief scene showing a waterfall flowing at a natural rate one moment then in slow motion the next, it appears as an abrupt manipulation, reminding the viewer that the film documents Trinh’s investigation of a perceptual phenomenon and not a culture’s essence. Arguably, this moment demonstrates, to quote Trinh’s script, “the shape of living, caught in the unfolding course of a digital plane”. In other words, it glimpses the fourth dimension; filmic time and lived time coincide.

The temporal conjunctions that are explored in and through The Fourth Dimension echo the idea of ‘reading across’, proposed by Trinh during a conversation with NTU CCA director Ute Meta Bauer at Wattis in September 2019. Simply put, to read across is to engage a text in simultaneous operations. It is to engage, for example, poetry as both poetry and philosophy or vice versa (in a literary tradition in which the two are kept separate). It could even read poetry into film. “Information can come in many ways, and it doesn’t have to be descriptive,” said Trinh. “And this is where resistance comes in, because with theory, the analytical mind, the dissecting mind, is very sharp. With poetry, on the contrary, ‘I’ is not just this individual, but ‘I’ is an open space where every ‘I’ can come in.” Reading across frees a text from its boundaries and frees a person from the limitations of selfhood; it is an extension of ‘speaking nearby’, wherein selves commingle through the written word, or with the moving image.

dir Trinh T. Minh-ha, 108 min. Courtesy Trinh T. Minh-ha

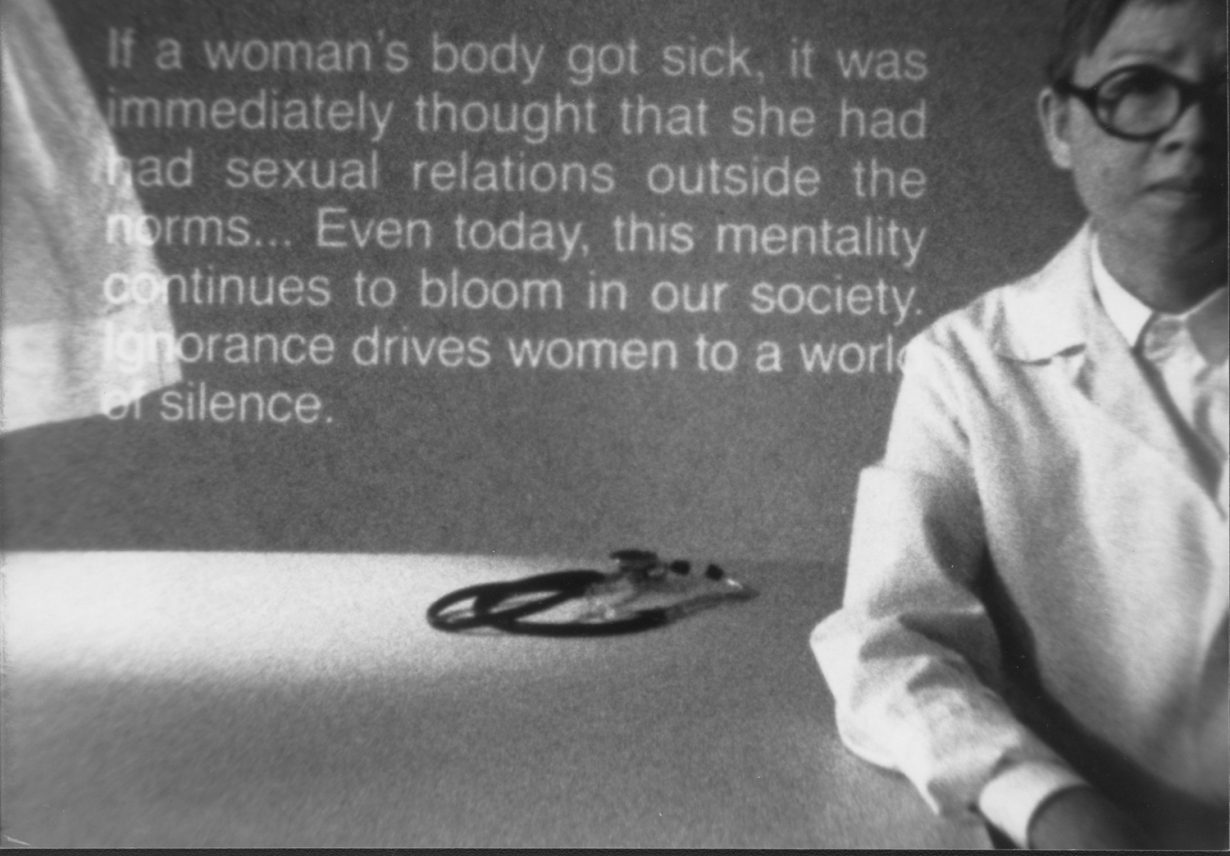

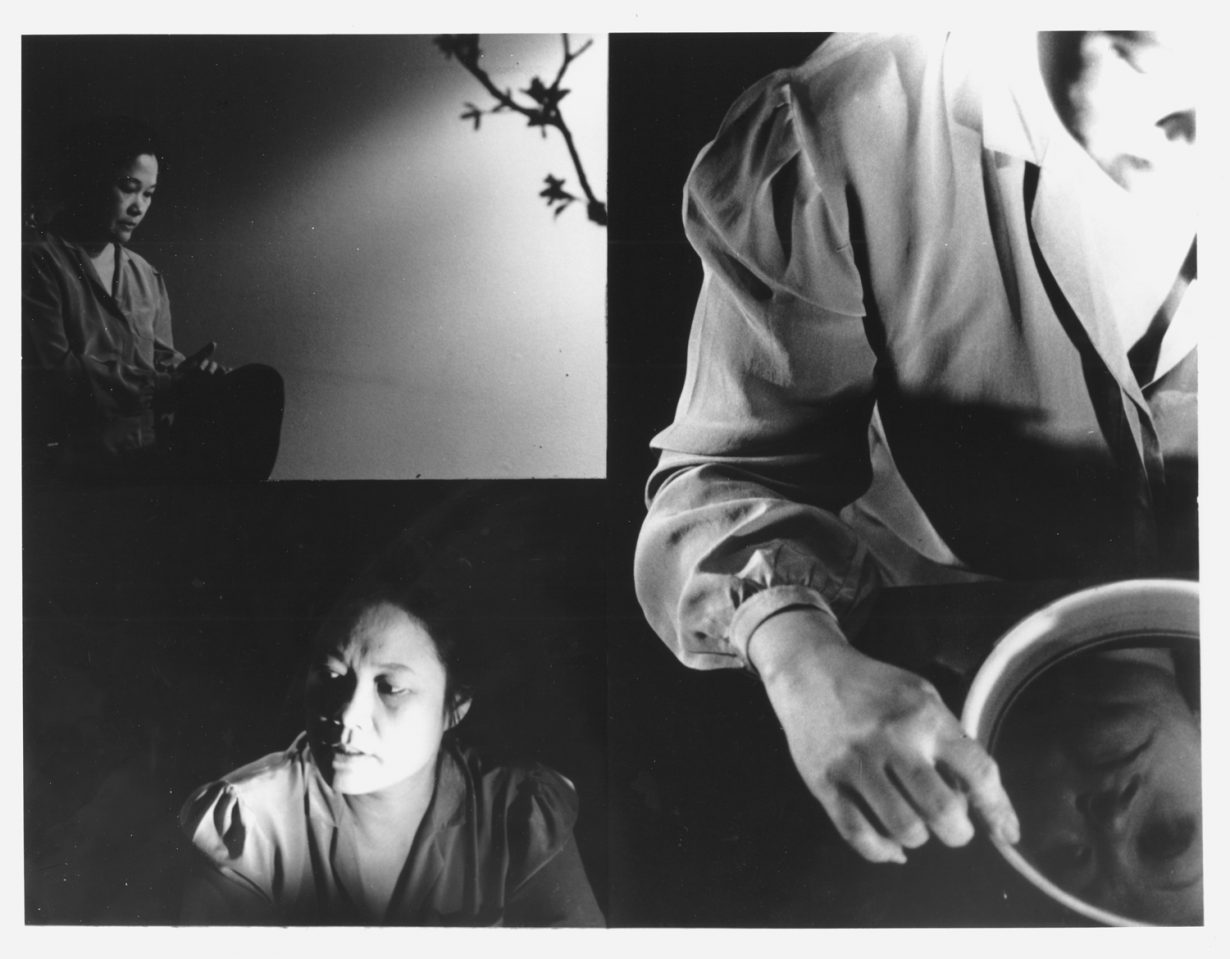

Surname Viet Given Name Nam (1989), a collage film, explores the concept of the poetic ‘I’ through a series of displacements. Five Vietnamese women living in the United States recount hardships they endured in their home country and as immigrants. What appears to be a garden-variety documentary loses its centre when it is revealed that the interviewees are nonprofessional actors interpreting the words of other Vietnamese women whose experiences are different from but resonant with their own. Speaking nearby becomes a manner of issuing respect as it unfolds between Trinh and the characters, Trinh and the actors, and the actors and the women they portray. Identity is at issue for them, none of whom testify or concede to an immutable self, despite the pressures of familial obligation, national loyalty or the curious camera, all of which conspire to fix them as mother, if not daughter of the state, if not an immigrant.

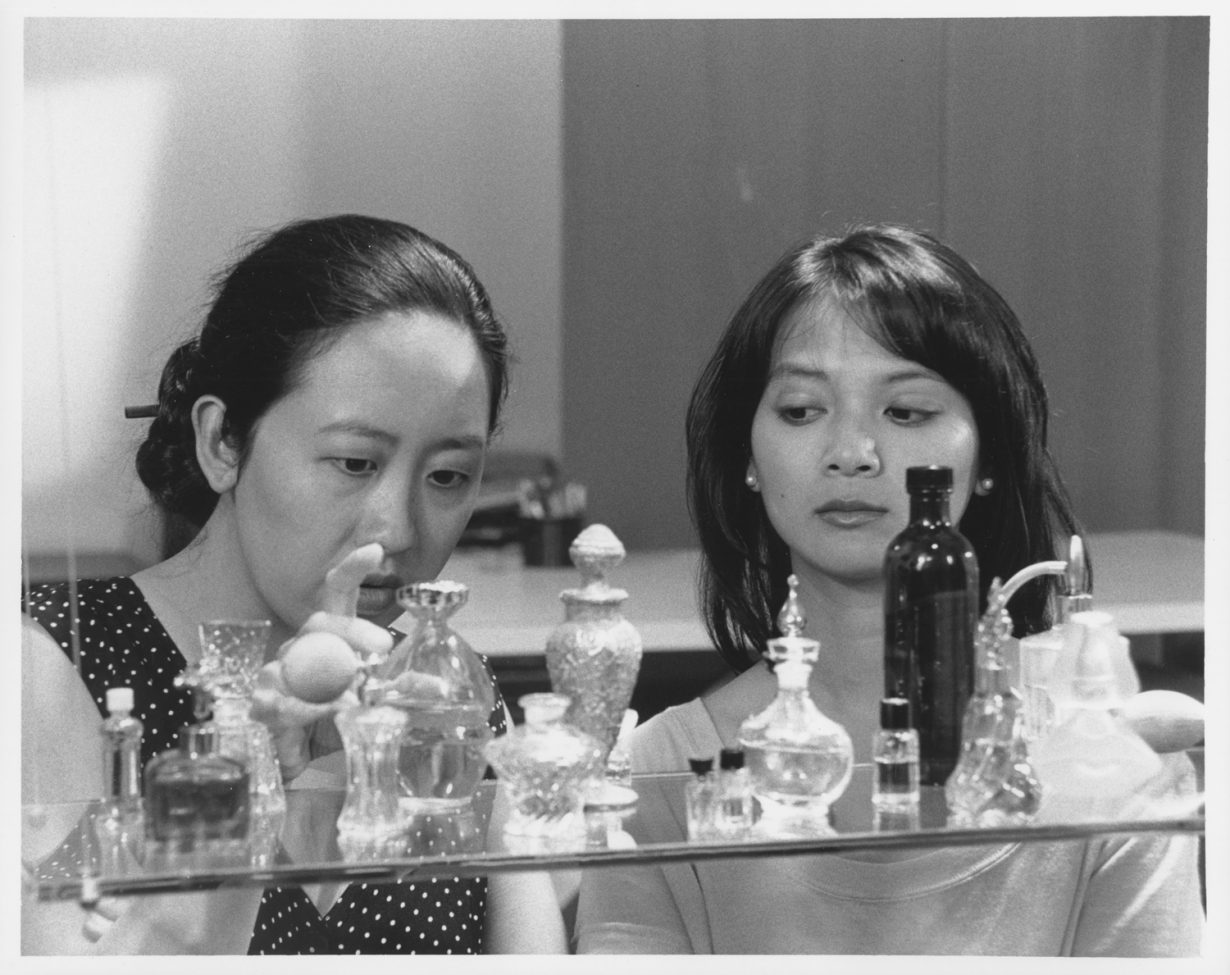

A nineteenth-century epic poem, The Tale of Kieu, by Nguyen Du, which is considered a treasure of national literature in Vietnam and an allegory for the history of the country, figures as a point of reference in Surname Viet… and as the narrative fulcrum in A Tale of Love (1995). Codirected with Trinh’s husband, the artist Jean-Paul Bourdier, A Tale of Love portrays a young Vietnamese immigrant navigating her life as a writer and a model in San Francisco. Her circumstance loosely parallels The Tale of Kieu, even as she analyses the poem from a feminist and diasporic perspective. Like her counterparts in Surname Viet…, she maintains a multiplicity of roles, undeterred by the demands of any single category: devoted daughter, serious scholar, erotic muse and self-proclaimed ‘woman of the nineties’. She moves across simultaneous realities unfolding in the course of her own character. Sometimes, she speaks nearby herself.

Courtesy Trinh T. Minh-ha

And in the digital film Night Passage (2004), Trinh and Bourdier adapt Milky Way Railroad (1927), a novel by Kenji Miyazawa, to similar effect, yet the multiplicity in question pertains to ‘reading across’. In this sci-fi narrative, three youths ride a spectral train on a journey between life and death, passing through a series of fantastical zones. Considering their train ‘runs on words’, one can speculate that the characters occupy a textual limbo, and the film’s title refers to both their travel and the various discourses on mortality, spirituality, language and time that they find in each zone. Theirs is an adventure in embodied cross-reading; the multiple Heavens they encounter are their texts.

So how does one reconcile the equanimity of ‘speaking nearby’, the kinship produced by ‘reading across’ when one confronts repugnant ‘speaking about’, when ‘one watches things that make one sick at heart’, as writes Nguyen in The Tale of Kieu? One lives by the ethics of both. One reads across the lines of one’s own station to express solidarity with, for example, a marginalised community without lapsing into saviourism, lip service or moral superiority. In 2020, such a lesson could not be more relevant to allies of the Black Lives Matter movement whose own lives have not been marked by police brutality; or, in the United States, to those who are counteracting anti-Asian coronavirus racism but who have never known racist mistreatment. (People like myself.) The enduring relevance of ‘speaking nearby’ is its protest and inherent respect. Its enduring power lies in the human dignity it preserves.

Trinh T. Minh-ha. Films. at NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore, is on view until 28 February 2021

Patrick J. Reed is an artist and writer based in Los Angeles