The late author’s posthumous collection Still Pictures reveals the anxiety and acuity of a writer’s life – and questions the very act of its telling

Janet Malcolm’s The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes (1994) will always be my primary Malcolm. It provided me with an early treatise on the writing profession, and stressed the responsibility of all practitioners in developing a clear understanding of what they mean by ‘truth’. Malcolm took as her subject not only Plath’s life, but her mythos: two distinct entities that diverged on account of the many projected fantasies of those who both adored and resented her. Through the book, I learned that a system of ethics was applicable as much to art as any other discipline, albeit through an insistence on a certain, ontological integrity. Art is at far greater liberty to subvert, transform and interrogate ideas of truth than reportage, for example, but it must nevertheless remain conscious of, and deliberate in those efforts. At a time when society seems transfixed by questions of celebrity, image, truth and post-truth, The Silent Woman seems more immediately deserving than most of a popular revival.

By applying the acuity for which she was famous to one of the most emotionally fraught and complex legacies in popular culture, Malcolm imparted far more humanity onto its central character than those who had gone before her. That Malcolm took matters of biographical fidelity so much to heart, makes a consideration of the recently published Still Pictures: On photography and memory (Granta, 2022) – a collection of autobiographical writings made by Malcolm in response to a series of photographs from her early life, and just a couple from adulthood – all the more challenging. Biography, for Malcolm, is ‘the medium through which the remaining secrets of the famous dead are taken from them and dumped out in full view of the world’. Autobiography might be a slightly different beast, but the perils of approaching it critically are not dissimilar. If I am persevering with wading through that dump, it is partly on account of how far I trust Malcolm’s thorough methods of interrogation, and their ability to diffuse the kind of hyperbole and excessive romanticisation that fuels the cult of the dead literary celebrity.

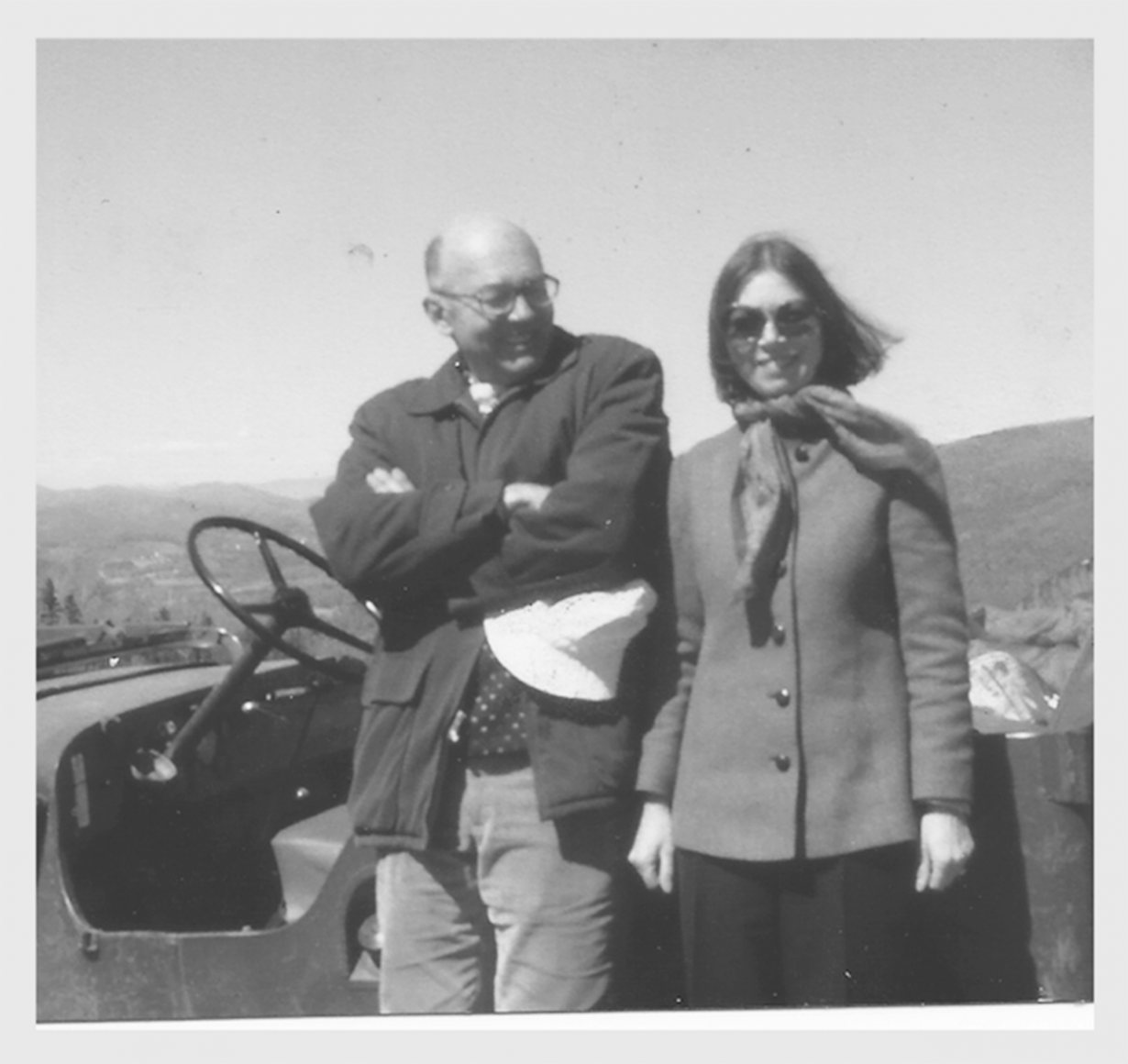

In her response to these photographs, which seem to be chosen for their incidental character – never captured at particularly auspicious moments or with any particular artifice, showing Malcolm, her friends and her family as they were, in their various moods and fickle fashions – we receive a version of her that is gentle, reflective and exposed. In this sense, Still Pictures serves as a neat counterpoint to the cool, steely work produced during Malcolm’s years at The New Yorker, for example, an institution whose god-like authority and machinations are also picked apart in the text. And she recalls that phase of her professional life with some embarrassment: ‘I put myself above the fray; I looked at things from a glacial distance… I was part of the The New Yorker of the old days – the days of William Shawn’s editorship – when the world outside the wonderful academy we happy few inhabited was only there for us to delight and instruct, never to stoop to persuade or influence in our favour’. (It’s perhaps worth noting Malcolm’s marriage to Gardner Botsford, heir to the dynasty that funded The New Yorker and also its one-time editor.)

Though there is a pleasing circularity to this story of one of America’s most famous journalists: Malcolm begins by stitching together a story of Czech Jewish immigration (Malcolm’s family fled Prague in 1939) to the United States, and Manhattan specifically, and ends with her mildly disdainful reflections on her younger, professional pretentions. Over the years that followed, she and her family contended with both the universal burdens of the displaced (the need to find stable housing and jobs, to assimilate, to adopt to the cultural mores of the longer-serving residents, to achieve some kind of prosperity), and the very specific challenges of their time, place and ethnicity: the unfamiliar world of consumerism, and the occasional encounters with antisemitism.

Malcolm adopts her usual methods of enquiry, cautioning herself against excessive speculation, and adhering where possible to the evidence that is presented on the page. And yet the sparse nature of the text, still written with Malcolm’s typical aversion to verbosity and excess, lends it greater poignancy than if it were otherwise. Most evidently, it recalls the haunting collages of another WWII survivor and witness to the holocaust, W. G. Sebald, who used the often-ambiguous interplay between his chosen images and text to create cognitive lapses where only the full horrors of genocide might be gleaned, and much more effectively than if they were described in full detail. Malcolm’s own assemblage operates by a slightly different model, as she commits to a process of description and dives with characteristic discernment into each picture. It is the refusal to extrapolate much beyond what we can see, or to assert anything that is not self-evident or corroborated – or else amusing us with endless qualifiers and caveats – that provides the most vivid impression of Malcolm, her repressions and her evident dislike of the arrogant authorial voice.

We are also provided a backdrop to this approach, and the circumstances of a writing career that often confounded critics. Malcolm is Czech before anything else and her work is indebted to the literary traditions of Europe in the first half of the twentieth century. None of which may be surprising from a writer who famously grappled with the modern practice of Pyschoanalysis – her book Psychoanalysis: The impossible profession (1981) gave insight on the many idiosyncrasies that Freud’s system had undergone in the years since its inception. Freud’s influence extends to Malcolm’s ever-present awareness of how memory might be distorted by the ‘narcissism of small differences’: how a European disdain for the almost mercenary individualism of her American neighbours, and those who had assimilated to the culture of the host, might have led to an unfair assessment of their character. Of one set of neighbours growing up, she writes, ‘They were modest, kind, good people who brought out an obnoxiousness in my sister and me for which I would blush today if I were a better person. But a child’s cruelty is never completely outgrown.’ She places the worlds of ‘money and business’ and ‘literature and art’ in perpetual opposition, observes the gradual erosion of her family’s cultural heritage under the imperatives of social mobility, and how a Dadaist sensibility – alongside the absurd Czech humour made famous by Kafka – inflected her day-to-day life, with its withering impression of American modernity.

This is the life of someone who was able to ascend to the highest ranks of the cultural establishment, challenge its approaches – sometimes intentionally, sometimes not. She did so in ways that seemed mystifying in real time but become clear on reflection hastened by this text. Certain reviews of the book have suggested that Malcolm ‘hides’ herself from the page, and so fail to grasp the main point: that her entire career might be read as a challenge to the very western, somewhat imperialist view of the ‘author as god’.

Such judgements are never relayed in the present tense, but at a remove; Malcolm is much less interested in bringing her reader into the conflicts that she herself grappled with, than considering the many ways in which they shaped the landscape of her early life. The judgements are ours to form alone. On the formation of memory, she is clear about the negative bias, as happy moments constitute random snapshots, while the morose and traumatic tend to be narrativized. ‘The memories with a plot are, of course, the ones that commit the original sin of autobiography, which gives it its vitality if not its raison d’etre’, she writes. ‘They are the memories of conflict, resentment, blame, self-justification – and it is wrong, unfair, inexcusable to publish them.’ Malcolm of course relays these moments anyway, but with an attempt to disturb the narrative by reflecting on the ways in which her own judgements may have been distorted – thereby finding for us some redemption. It is a final lesson, perhaps, from a writer who was always generous enough to expose the workings of her profession, and lay bare the methods of her approach: to tread lightly and with good humour, distrust the ego and to take heed of the incidental and the seemingly obvious, whose value to the artist and journalist resides in the fact that just about everybody else has dismissed them.