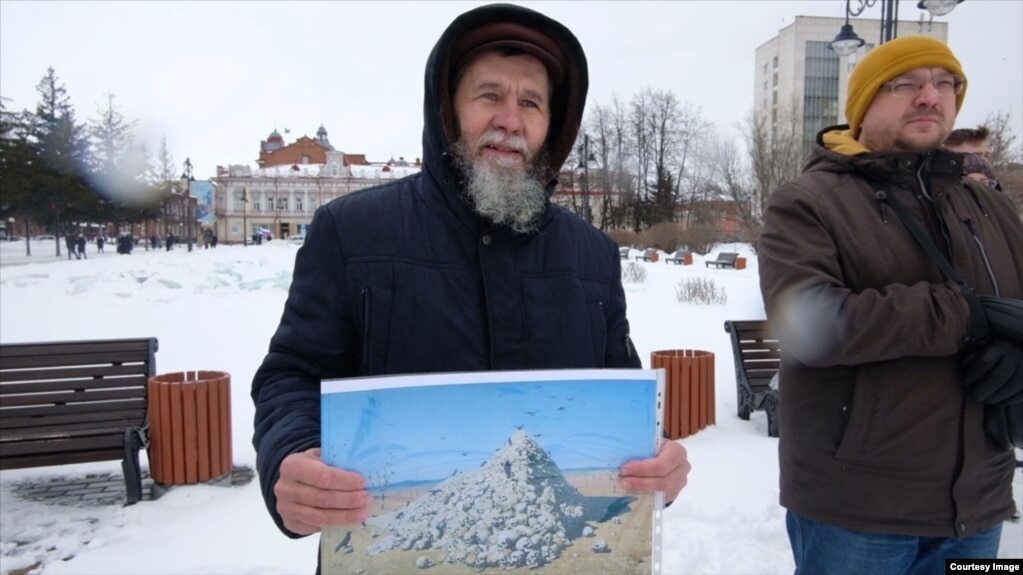

A carpenter in the Siberian city of Tomsk was arrested after he held up a print of the 1871 painting at an anti-war protest

On 6 March, Stanislav Karmakskikh, a carpenter in the Siberian city of Tomsk, was arrested. His crime was attending a small protest against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, in which he stood, wrapped up against the snow, holding a home-printed reproduction of Vasily Vereshchagin’s The Apotheosis of War. The gruesome 1871 painting shows a pile of skulls – the spoils of war – and was made by Vereshchagin following his attachment with the Imperial Russian Army as they conquered lands in what is modern-day southeastern Uzbekistan.

Reached over Telegram, Karmakskikh says his detainment happened when he intervened as the police arrested another protester, a young woman. “When I saw how the police were taking the girl away, I felt ashamed to stand aside and I approached them myself. I told them that the picture painted our future.” He says the police were momentarily unsure as to whether they should arrest him or not, but took him away to the local station from where he was eventually taken to court and fined 45,000 rubles (£420).

The slight hesitation by the local police is understandable. They are under direction to suppress all criticism of Putin’s invasion, part of the wider wave of repression that has seen all independent media shut down and any state employees, including cultural workers, removed from their positions should they speak out against the war. The Apotheosis of War however is an artwork that has become a national icon. The original hangs in the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. You can even buy socks printed with the painting’s skulls in the museum’s gift shop. Though Karmakskikh says he is unsure whether it was specifically the painting that annoyed the officers, nonetheless given their anti-war message these are now socks that will presumably mark their wearers as “scum and traitors” in the eyes of Putin. In a televised meeting with officials on 16 March, the president promised a “necessary self-purification of society”.

Vereshchagin had signed up to be an official artist for the military, but the horrors he witnessed turned him against war and particularly imperial aggression. In the museum’s official interpretation of the picture, its curators write: ‘All further work and life of Vereshchagin were devoted to the protest against all wars.’ In an inscription on the frame the artist wrote, in a line that should be read ironically, ‘Dedicated to all the great conquerors: past, present and future’.

Karmakskikh, who is a member of Tomsk Memorial, a small activist group founded after the 2020 poisoning of opposition politician Alexei Navalny, admitted “of course there is fear”, but it is the memories of his youth that drew him to the picture and led him out to the streets. “It seemed to me the most relevant moment. I was very interested in how the human bones most fully reflected the repressive spirit of the Soviet era. And now they also show Russia.”

For a brief moment last week, the pro-Kremlin Russian tabloid Komsomolskaya Pravda estimated that 9,861 Russian soldiers have been killed during the war with Ukraine over the past month and another 16,153 have been wounded. The figures were quickly deleted from the online article. The UN says over 1,000 Ukrainian civilians have been killed.

The painting’s pyramid of skulls, which has a strange anachronistic resemblance to the piles of sandbags that residents of various Ukrainian cities have stacked up to protect public monuments and artworks from damage by Russian airstrikes, is shown amidst the barren desert of the Uzbek steppe. There are some trees, but they are devoid of foliage, and in the background a city stands in ruins. The only life in the painting is that of birds – crows perched on the remnants of the dead soldiers – as further symbols of death. The curators at the Tretyakov interpret this morbid landscape as a reminder of ‘how fragile the world and human creations are, and how easy it is to completely wipe out flourishing and precious human life from the face of the Earth in the strife of people.’ Not content with destroying Ukraine’s culture, Putin’s war undermines Russia’s too.