The recent controversy over artist Anita Dube’s unauthorised use of an anti-establishment poem by Aamir Aziz reveals the deeper inequities of caste privilege within Indian society

Where does the line fall between appropriation and homage? Last month, internationally recognised artist Anita Dube was accused of using lines from an anti-establishment poem in her work without offering ‘knowledge, consent, credit and compensation’ to its author Aamir Aziz. Best known as a member of the short-lived but highly influential Indian Radical Painters’ and Sculptors’ Association in Baroda, Gujarat during the 1980s, and for being the first female curator of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, Dube has consistently argued for an expanded perspective on what art can be and how it might be used to political and even subversive ends. A cofounder of Khoj, an international arts organisation in New Delhi, Dube is often associated with a form of radicalism that has seen her denounce the commodification of art, as outlined in her 1987 manifesto ‘Questions and Dialogue’, in which she stated her commitment to using industrial materials and inexpensive objects in the making of her works, alongside attempts to engage with working-class audiences.

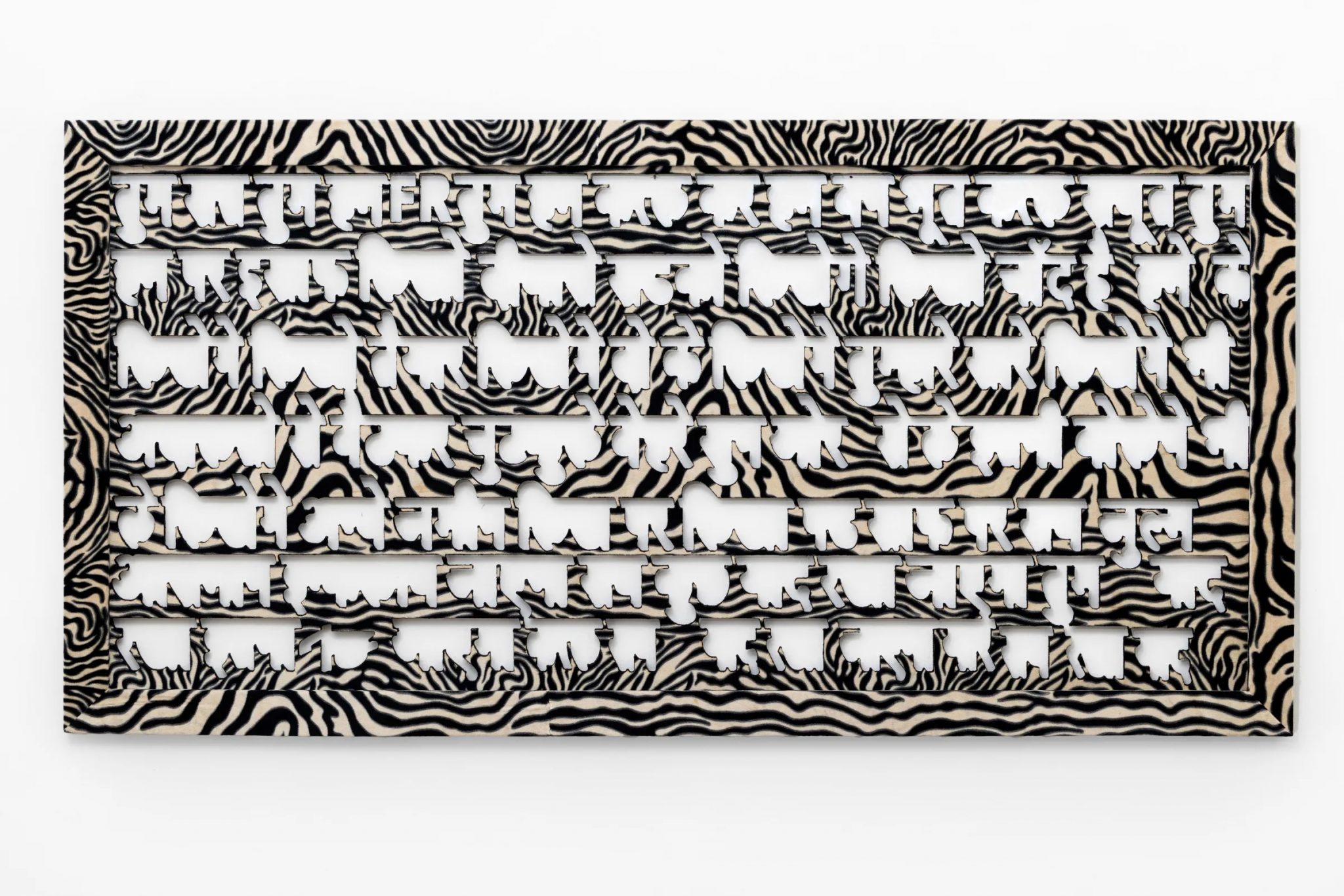

In a post circulated on social media in April, the Mumbai-based poet and writer Aziz alleged that Dube’s use of his poem Sab Yaad Rakha Jayega (Everything Will Be Remembered, 2020) in artworks exhibited at a recently concluded show at New Delhi’s Vadehra Art Gallery, titled Three Storey House, did not amount to either solidarity or homage, as Dube would later claim. While clarifying that he would stand with people who used his poetry in, say, a people’s uprising, Aziz argued that embroidering his verses onto a velvet cloth, a material historically associated with luxury, royalty and wealth, was against the very ethos of his words. The previously untitled work was renamed After Aamir Aziz (2023–2024) only after Dube was sent a legal notice. Other works in the show, including Small Zebra (2023-24) and Old Zebra (Disappeared Poem) (2023), also incorporated Aziz’s words into velvet, and while the former was renamed Small Zebra – Fragments from Aamir Aziz’s poem ‘Sab Yaad Rakha Jayega’, the latter continues to use its old title. Aziz has been clear that from his perspective, Dube’s actions amounted to theft and erasure, and were an act of extractive consumption and profiteering masquerading as a gesture of solidarity and radicalism within the context of a commercial art gallery.

Sab Yaad Rakha Jayega was performed by Aziz during mass protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), a controversial bill (later passed as an Act) introduced by the far-right Hindutva-driven Narendra Modi government in 2019 that allows for the granting of citizenship to religious minorities escaping persecution from neighbouring countries but which excludes Muslims from the same. CAA, along with the National Register of Citizens (NRC), that aimed to verify all Indian citizens, has been called ‘India’s first Nuremberg law’ for its discriminatory nature. Aziz’s poem refers to the government’s highhanded attempts at squashing dissent, including the dozens of deaths due to police and mob violence and the hundreds of protestors who were arrested, and speaks of how not only would every act of violence be remembered, but also that nothing would stop people from taking to the streets and pushing back against these draconian laws. His is protest poetry at its most effective, and it quickly transcended national borders and gained an international following; at a gathering in London to demand the release of Wikileaks founder Julian Assange in 2020, Pink Floyd cofounder Roger Waters read out an English translation of the poem in solidarity with those protesting in India.

Aziz’s poem has had a life story of its own, speaking truth to power and standing in solidarity with those who find themselves disenfranchised under authoritarianism, fuelled by capitalism and religious majoritarianism in India today. By appropriating his words for works of art that are displayed as commodities within a commercial space, Dube’s act seems unintentionally ironic at best, and shameful at worst. Galleries, at least in India where the viewing of exhibitions of art is uncommon as a form of cultural entertainment and are usually restricted to urban metropolises, rarely see visitors from the marginalised communities with which Aziz writes in solidarity. That Dube’s works were exhibited in a space that can often feel out of reach or alienating to many only deepens the fundamental contradiction of Dube’s alleged appropriation with the origins of Aziz’s poetry.

Copyright infringement and attempts at erasure aside, it is an ethical question that reveals how even basic manners and respect for fellow artists seem to stand outside the halls of liberal, upper-caste privilege and the sense of entitlement it brings. Dube is a Hindu Brahmin surname (although more commonly spelled as Dubey), while Aziz is a Muslim, part of the persecuted minority in today’s Hindu majoritarian posturing. Under the varna, or social class, system in Hinduism, Brahmins are at the top of the ladder. Although those of other religions (like Aziz) do not fall under the Hindu caste system, minorities like India’s Muslim population are still seen as unequal to Brahmins. Historically and to this day, being born in an upper caste has given people easy access to education, to careers in powerful sectors like politics, administration and business, and by extension, access to networks that can help create wealth. Caste privileges permeate every aspect of public and private life in India, and the rarefied world of art is hardly exempt from it.

One wonders if Dube would have been just as nonchalant if it was a writer or fellow-traveller, as she calls them, from the same social background as herself. In a poorly-worded ‘apology’ post, Dube displays an evident sense of bewilderment, as if she doesn’t quite understand what the fuss is about. In her insistence that she was only celebrating the poem – by using Aziz’s words without acknowledgement, let alone permission, lest one forget – Dube expressed nostalgia for what she called a ‘lost old world where there were fellow-traveller solidarities’ and ‘spirit of the Commons and Copy Left [sic]’. Despite admitting to an ‘ethical lapse’, she explained that she had offered Aziz renumeration to ‘correct’ the situation, while any identifiable sense of shame, guilt or remorse remained elusive. Aziz has called Dube’s offer ‘insulting’, and termed her creative theft ‘the oldest trick in the book, … steal the voice, erase the name and sell the illusion of originality’. It is clear that Dube is not sorry she stole; she is only sorry that she was found out. For all the egalitarian ideals she claims to uphold, this act dismantles her aura of a radical artist.

Allegations of plagiarism and theft of intellectual property by artists from marginalised communities against upper caste artists continue to be all too common. Even as the Aziz-Dube episode was being discussed in various media and cultural forums, the Tamil writer and journalist Jeyarani, a Dalit, accused the upper-caste film director Shalini Vijayakumar of plagiarising her short story Sevvarali Poocharam and adapting it as Seeing Red, a film that premiered at the prestigious Mumbai Academy of Moving Image (MAMI) film festival last month. Vijaykumar has since denied the allegations, saying that the film is an original work.

In societies like India that are rotting from the inside because of the oppressive rigidity of caste, it is galling to see upper-caste artists like Dube cherry-picking the labour of so-called fellow-travellers for their own gain. Fittingly, Aziz’s poem addresses those who sweet talk in public in the day, only to come back at night and attack those who demand their rights, blaming them for being the perpetrators. Little could he have imagined how literally these words would play out.

Deepa Bhasthi is a writer based in Kodagu, southern India