As technology catches up to the futures animation has depicted, what lies behind the dazzling promises and flawed predictions?

Whether relaying the vast cosmic displacements of Cixin Liu’s Three Body Problem series (2008–10), or the intimate transmogrifications of Charlie Jane Anders’s alien allegories of bodily dysphoria, a basic material contradiction underpins even the most future-oriented science fiction writing. No matter how far-reaching its speculations, how accelerated its hypotheses or how industriously sculpted its emergent worlds have been lyrically terraformed, readers are always left grasping the same remnants of a patently antique media: paper and ink, or their luminous electronic approximations, the epub or pdf.

It’s an irony that theorist Scott Bukatman sensed back in 1994 in his wonderful essay ‘Gibson’s Typewriter’, noting the curious dissonance between the analogue Hermes 2000 on which William Gibson’s 1984 novel, Neuromancer, had been hammered out, and the era of electronic deterritorialisation the book had untethered. Bukatman resisted the urge to read the anecdote as a simple parable of epochal shift, instead suggesting it serve as a narrative of techno-historical contamination in which disorderly pasts seep into, and perhaps taint, any ordered visions we have of the future. It leads us to wonder how the same tension might vibrate at the heart of other media we commonly press into the service of futurity. What about animation, that liquid vector of fabulation coursing with its own protean intensities and brain-dissolving phantasmagoria? How do we frame and position its affordances? If the modern novel is science fiction’s trusty steed, then animation is its blazing warp drive, a hyperbolic imaginarium in which thematic innovations incubate their own technological evolutions.

While mid-to-late-twentieth-century literary science fiction was star shipping its troopers onto intergalactic adventures while raising a metaphorically cyborgian middle finger to any stable notion of the human, animation was literally illuminating the image repertoire of late modernity with its own startling flair. From Forbidden Planet’s extraterrestrial demon sketchily penned onto the blasted plains of Altair IV (1956), through Tex Avery’s archly probing World of Tomorrow skits (1949–54), to René Laloux’s pastel-hued fable of interplanetary subjugation, Fantastic Planet (1973), animation operates with a strange immediacy to the far-seeing imaginaries of speculative fiction.

This is partly due to its mechanical heterogeneity; the interwoven tools and applications of animation production mirror the technopolitical dream of science fiction’s scrambled circuitries and glowing interfaces. Scholar Deborah Levitt describes animation as a ‘super-medium’ for good reason, acknowledging its simulations as the cobirthed products of interdependent platforms and postproduction packages. But it’s also due to the fact that in striving to visualise the as yet unseen, animation induces its own conditions of transformation, something that Bukatman keenly observed in his 1993 book, Terminal Identity, when suggesting that James Cameron’s Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) didn’t just narratively evoke the development of a liquid metal killing machine, but invented its own technology to manifest one.

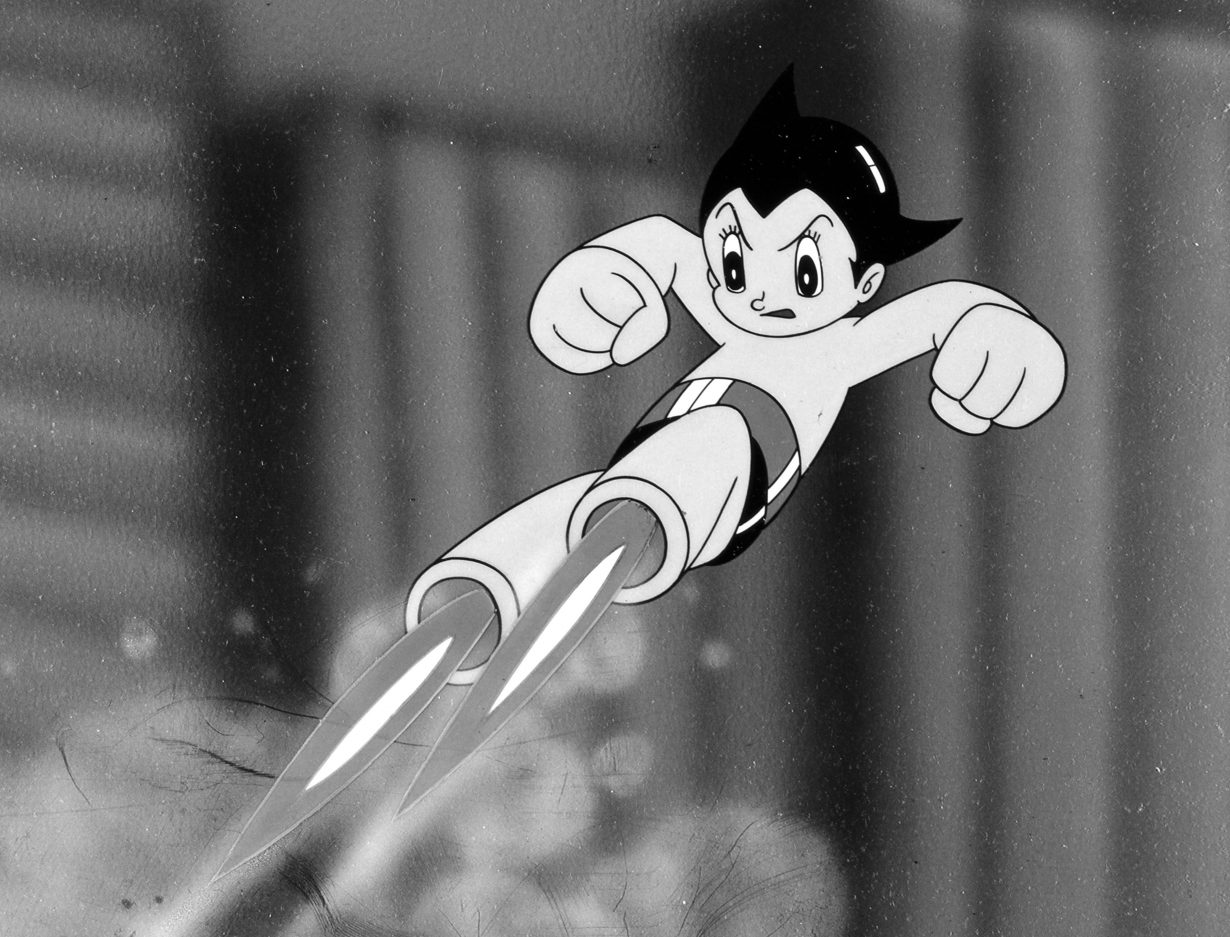

During the late 1980s and early 90s, Japanese anime was developing its own distinct texture of speculation in which multiplanar cel animation was pushed to newly expressive limits. The comforting momentum and jocular tone of children’s shows such as Astro Boy (1963-66) and Mobile Suit Gundam (1979-80) were supplanted by hardened adult narratives forged from the burnished tech of a world awakening to the deregulated nightmare of a newly networked capitalism defamiliarised by cyberpunk. Yoshiaki Kawajiri’s Cyber City Oedo 808 (1990), Koichi Ohata’s Genocyber (1992) and Yukito Kishiro’s Battle Angel (1993) seethed with a neon-soaked luminosity as shocking as the corporatised cruelty they thematised, while arthouse classics like Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira (1988) and Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell (1995) molecularly reconfigured the human body through an unprecedented optics of transhuman transgression.

In the UK and US, the Island Records video distribution subsidiary Manga Entertainment would translate and market these works with a crude techno-Orientalist panache that promised to ‘blow your mind into the twenty-first century’. Playing on a broader international consternation that Japan’s ‘economic miracle’ might be a locus of unrestrained technological hubris, this fetishisation of futurity positioned animation as oracle while reinscribing Asian culture as a hazily defined headspring of the weird and the uncanny. In retrospect, it’s easy to perceive this as a project of gawkish othering and dehumanisation that had been operative in ‘Western’ culture since at least Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu writings of the 1910s, but certainly intensified by things like Blade Runner’s 1982 depiction of glowing rain-slicked noodle stands and holographic geisha punctuating the dark streets of a future-gothic LA. In the work of Takayuki Tatsumi – a theorist whose writing reads with the scorching velocity of sci-fi – such simple narratives of one-way transmission are wryly chastised. Evading redundant notions of source and origin, Takayuki suggests a ‘multicultural and transgenic poetics of chaotic negotiation’ that mobilises Japan’s science-fiction exports as signals within an endless relay circuit of transcultural influence. In a wired society, the condition of weirdness is ubiquitous and thoroughly distributed.

As films like Mamoru Hosoda’s Belle (2021) and Makoto Shinkai’s Suzume (2022) continue to elaborate anime’s visual complexity with intricate narratives to match, it’s curious to note a newly hostile fan culture surrounding procedurally generated imagery, deep learning and AI-appended shortcuts. Anime may have once been positioned as a vanguard of technological ambition, but now its viewers tout a formal conservatism, demanding carefully constructed sequences, hand-finished backgrounds and the attention to detail of a human creator. Approaching the release of Hayao Miyazaki’s latest film, The Boy and The Heron (2023), footage of the comedically dour director declaring AI animation ‘an insult to humanity’ back in 2016 is recirculating with a renewed bite as the industry confronts the threat of automation.

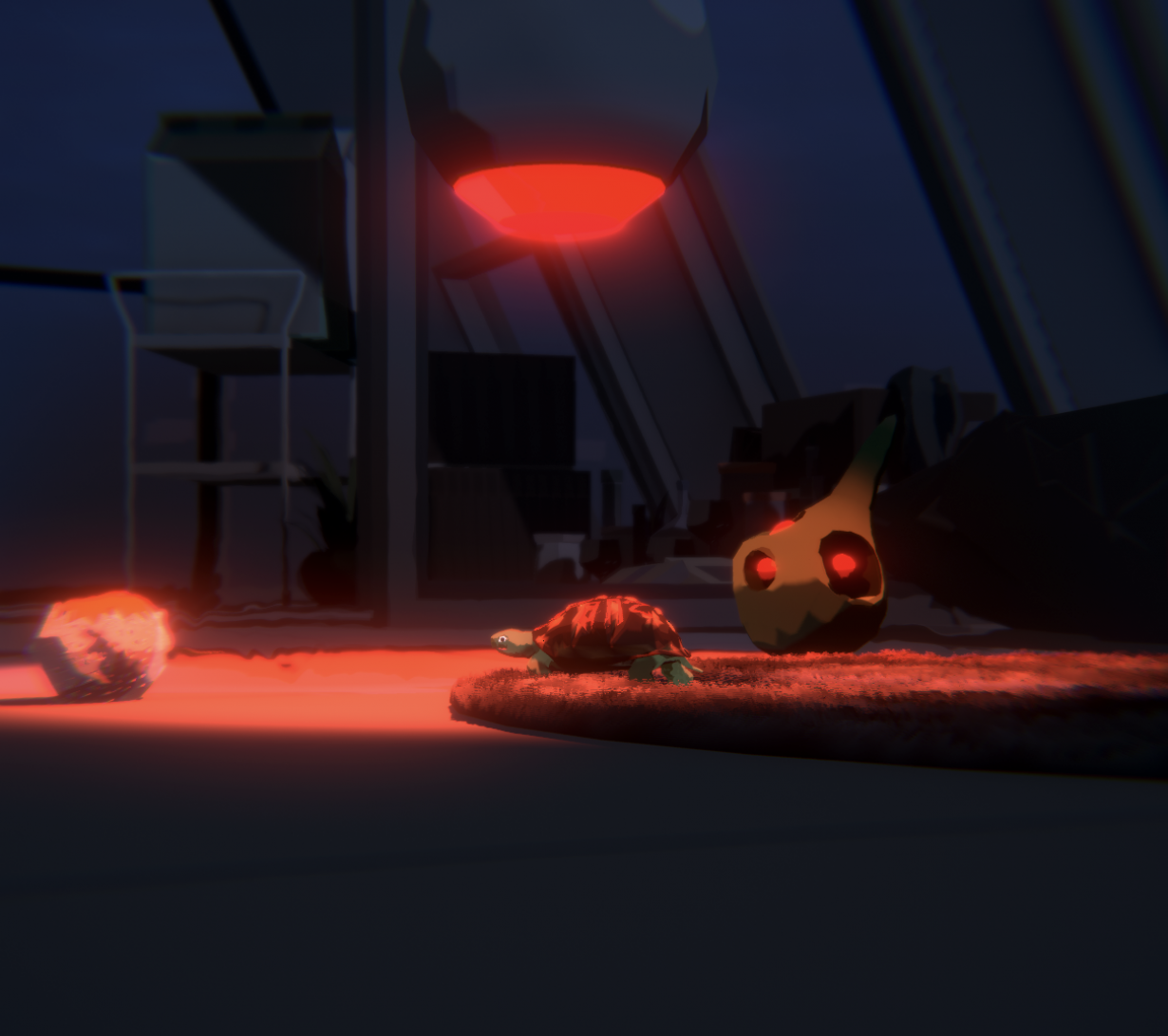

Perhaps this scenario is where artists are best positioned to provide partisan commentary on a technological narrative often obfuscated by its own dazzling impressions and innovatory prowess? Ian Cheng’s Thousand Lives (2023), Bob Bicknell-Knight’s Non-Player Character (2022) and Kara Chin’s Inaugurare (2023) are all anime-adjacent artists’ films that attempt to inhabit apparently pathetic digital assets as melancholic ciphers of animation’s future orientations, each foregrounding dynamics of uncertainty, obsolescence and flawed prediction. In contrast to the general velocity of industrial advancement, these works perhaps betray a tendency to linger contemplatively with the medium’s recent histories, its pitiable characters, its opportunities for failure and projection. As commercial animation forges ever-new techniques for the creation of alluring imagery and simulation, what might artists gain by sifting through the debris like the e-junk gleaners so common to William Gibson’s fiction, questioning the very promise of futurity we seem to have encrypted in the medium, finding their own uses for things?