Across a career of seemingly endless experimentation and collaboration, a singular voice – and sound – remains

My first encounter with Ryuichi Sakamoto’s work was not his soundtrack to the David Bowie-starring Japanese new-wave film Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence (1983), with its crystal-clear classical piano outline still traceable in cinema today (it’s impossible not to hear Sakamoto in much of Jung Jae-il’s score for 2019’s Parasite, for example). It was not even the hugely influential techno-pop of Yellow Magic Orchestra, with songs as groundbreaking, disastrously catchy and utterly joyous as 1979’s ‘Rydeen’. Somehow I missed these landmarks, and arrived instead at the string of collaborations he recorded with German musician Alva Noto on the Raster-Noton label: Vrioon (2002), Insen (2005), Summvs (2011). I was a young and mostly unpaid music journalist, fresh off the back of a stint writing about mid-2000s electronica and digging Pan Sonic. The crisp perfection of these Raster-Noton albums spoke to me in their soft piano notes, razor-wire electronics and laser-cut percussive glitches on the edge of hearing. They were clean and minimal, restrained, but not lacking in emotional pull. I hear Vrioon now and return in an instant to the same headspace. What I didn’t know at that time was that the boldness of this collaboration with avant-garde electronics was in fact par for the course for a musician who had also won an Oscar, scored Hollywood films and been in one of the most influential of Japanese pop groups.

With catalogues like Sakamoto’s, we find our own way in and then through; our encounters are our own, although we may pass others along the way. A list of his bands, projects, collaborations, soundtracks, would stretch for pages upon pages, though there are the obvious checkpoints: YMO, solo albums like Thousand Knives (1978) or Sweet Revenge (1994), Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence. There have always been projects with household-name musicians and lesser-known experimenters: David Sylvian and David Bowie, but also production for Japanese singer Phew’s first single; a 2018 remix of Oneohtrix Point Never’s ‘Last Known Image Of A Song’; guest vocals on Arca’s kiCK iiiii (2021). There were bossa nova albums, field recordings, compositions for art installations, ringtones for Nokia and records upon records of electronic music – credited as contributing to the evolution of techno, cyberpunk, electro, funk and IDM. There are awards from major institutions (a lot of them), but within all this a consistent commitment to experimentation. The mainstream music industry he entered in the 1970s was one thing, but the opportunities and possibilities presented by more avant-garde or independent projects were always just as important. If we must point to what made his music his, there is a thread to draw out in the many returns to and reimagining of the possibilities of electronics and piano.

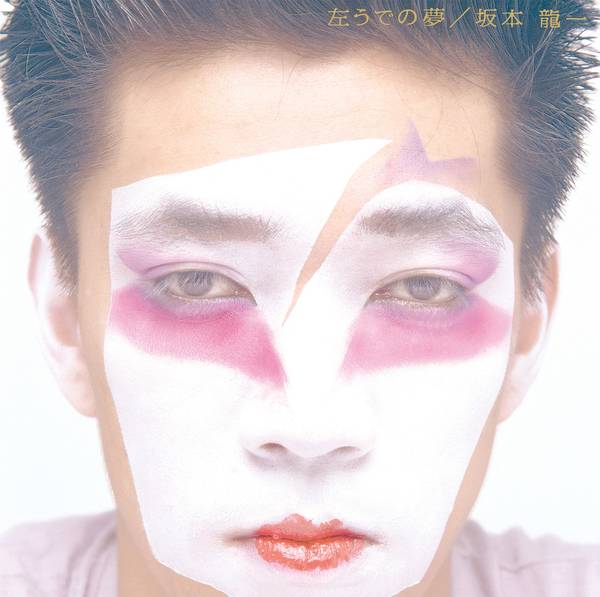

His is a catalogue frequently positioned alongside other behemoths like Brian Eno, with a taste for expanse and grand ambition; a fervour for ideas and a consistency of mood – with few dud notes. But I find myself increasingly returning to his electronic work from the 80s – albums like Bamboo Houses / Bamboo Music (1982) with David Sylvian, or the solo record Left Handed Dream (1981). They each possess a singular unmistakable character, an indisputable Sakamoto signature: brittle and glassy electronics that resolve with feeling, while possessing an almost impossible cool. Their detachment made his work feel unreachable, but their unwavering sincerity grounded it all in a time and place. References were often confidently explicit: think of Sakamoto with a classic 1950s crew cut and white T-shirt on the cover of Left Handed Dream (1981), a Bowie slice through modernist geisha face paint (the photographer Masayoshi Sukita was known for his work with Bowie).

In 2017 I was sent to review Ultima festival in Oslo, where on the final night I saw a performance by butoh dancer Min Tanaka, who moved to sound by Sakamoto in a fog installation by the artist Fujiko Nakaya. It took place on the roof of the then-unfinished concrete shell of the new National Museum. Rain pooled in the stairwells; puddles were bridged with plywood. Floodlights fixed to cranes sailed back and forth over our heads, illuminating Nakaya’s synthetic fog that poured onto the roof and then over Tanaka. His movements spoke of melancholy and despair, tracing an arc sporadically enveloped in the fog and then revealed by the wind. Sakamoto’s live sound tracked these gestures in restrained chimes and rumbles as Tanaka spun in the white mist, body and music aligned in a simple and arresting moment, a distillation of sound, light and movement into one. I was paralysed by its cinematic intensity: the soundtrack was with the image, not above it, nor beneath it. It did not exaggerate, did not tell me how to feel. It was entirely Sakamoto: rooted in a form of experimental dance that originated in Japan, interlocked with contemporary art and global pop music; chilly washes of synthesiser enveloping a hand gesturing to us from the mist. As fog wrapped around his shoulders, Tanaka let his head fall into his hands, and I became tearful: for something indeterminate; for a loss that was yet to come.