The tenor of current cultural and critical exchanges among South Asian and Gulf countries points to the contortions required of those who would correct art history

It was all going along so nicely. Just a bunch of people from London and Gulf-based American museums telling a rapt audience in Colombo about how they were going to make South Asian art great again. Until someone in the crowd declared that the Gulf is where South Asians “go to die”. And the talking stopped. The rather brutal premise formed the core of a ‘question’ posed by one attendee at a panel discussion taking place during last month’s KALA arts festival. The attendee was responding to a curator from the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi – a Frank Gehry-designed art behemoth whose PR bumf boldly promises a ‘new approach’ to museum making and ‘an experiment in inventive 21st-century museum design’ – who had presented a selection of past projects (broadly South Asian) on which he had worked in his career prior to arriving at the Guggenheim. The point of all this was that works by artists from South Asia are projected to feature prominently in the new Guggenheim’s opening displays (although when that opening is actually taking place remains a little hazy). Which you might expect, given the long relationship of trade and cultural exchange between the two regions, nowadays most visible in the billboards in Abu Dhabi featuring Bollywood stars plugging merch, and the brown bodies in the labour and service industries. But soon to be just as prominent within museum walls.

The curator’s narrative aimed to set up himself and the institution as ‘correcting’ art history, reversing the erasure of the Global South from a history written in and by the Global North. It’s a narrative that gets deployed a lot these days when the general rhetoric surrounding culture and, well, everything else, revolves around victims and perpetrators. Given the overall vibe of the KALA festival (bigging up Sri Lanka in particular, and South Asia more generally, via a series of exhibitions in commercial and noncommercial spaces with panel discussions, drinks receptions and dinners), the panellists were clearly expecting their audience to see all this as a good thing. Art history rewritten with South Asia at its heart. The centre of art moving a little bit east from its heartlands in Europe and the US (although that bit’s a little confusing with franchises like the Guggenheim, as you’re never quite sure if all they represent is an extended cultural colonialism controlled from New York). Still, given the expectation of positive vibes, the panel was rather taken aback when their interrogator suggested that you couldn’t do the correcting-art-history bit without addressing the more general injustices inflicted upon the Global South and particularly on those with darker skin who generally labour to construct the literal fabric of the institutions in which that correcting takes place. (At least that was what might be inferred from his much shorter and more clumsy interjection.) Indeed, the panel’s moderator decided to end the discussion then and there. Which most likely confirmed the questioner’s suspicions that any institutional engagement with South Asia didn’t have South Asia’s best interests at heart. That it was more a balm for the conscience of the institution itself, which had played a role in perpetuating the very cultural hegemony it was now boasting about tearing apart.

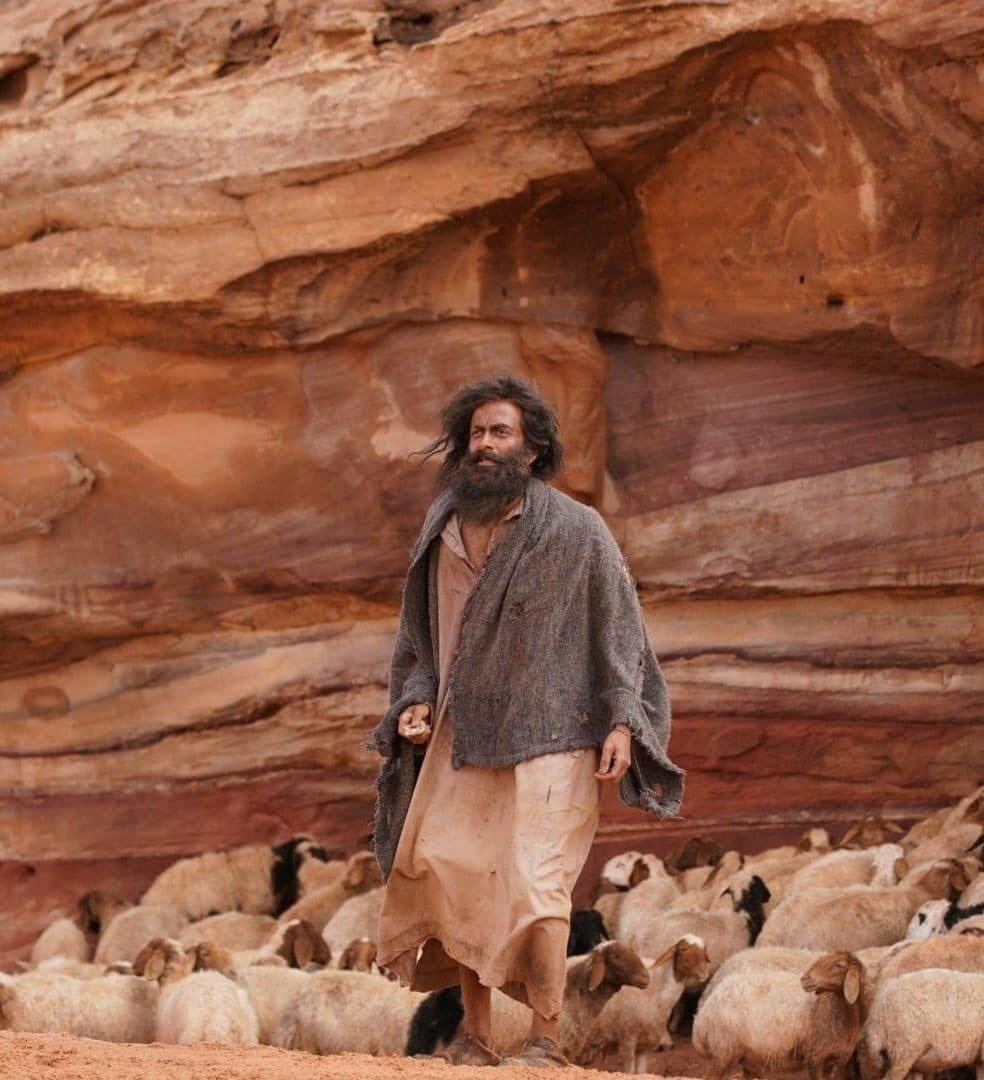

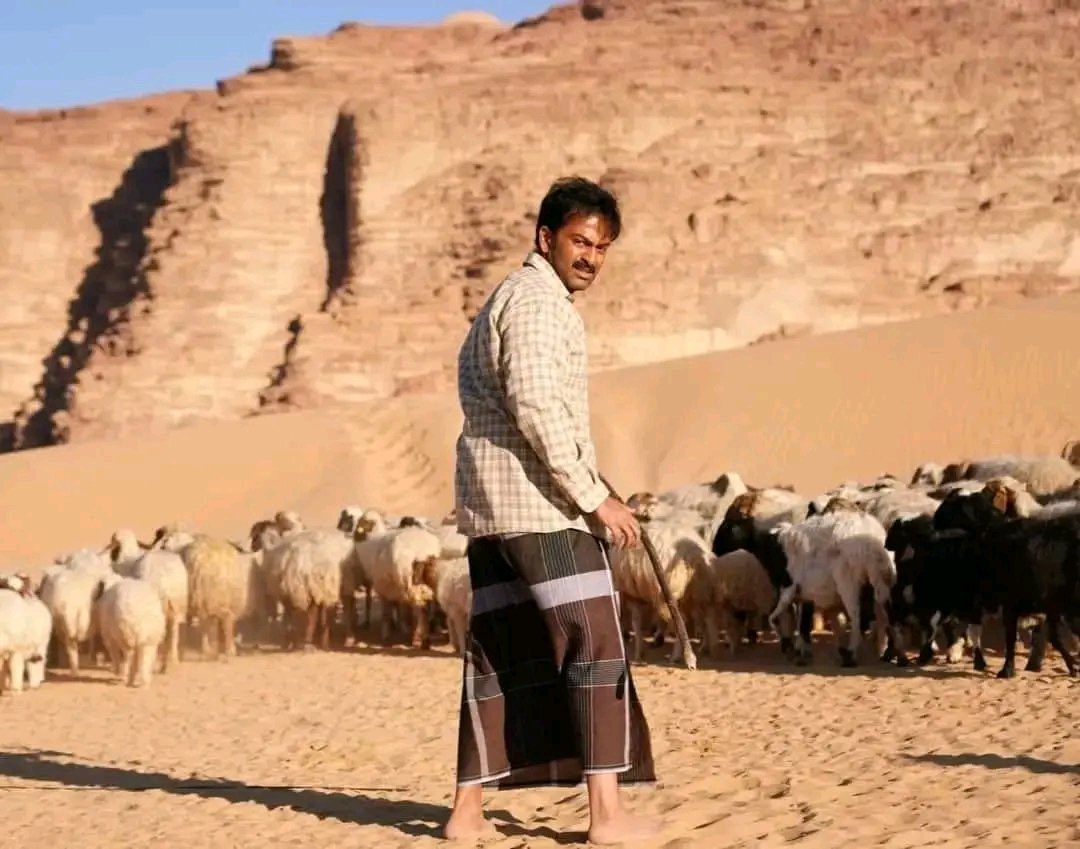

Perhaps these suspicions had been further fuelled by recent films like Aadujeevitham: The Goat Life (2024; adapted from writer Benyamin’s horrifically powerful 2008 Malayalam novel, apparently based on a true story). One of the highest-grossing Indian films of last year, it is an account of an Indian migrant worker who travels to Saudi Arabia following the promise of riches in the Gulf (offered by a series of dodgy-seeming brokers – generally friends of friends), but once he gets there is tricked into a form of contemporary slavery, spends his days tending beasts. He is treated as a beast, and comes to resemble those beasts. You become the situation that you are forced to inhabit: isn’t that what we learn when we learn about colonial histories? For the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard (who was less interested in colonialism), this relates to a primal instinct for self-preservation, and the way that people adapt themselves to assume the contorted forms of their hiding places, their ‘nests’, as he has it. It is our natural instinct not to stand out and make oneself a target: to remain part of the flock. This is what the KALA panellists had expected of their audience.

Or perhaps the interrogator had been browsing the Gulf Labor Artist Coalition’s (now rather out-of-date) website. The group, founded in 2011, had been advocating for improved working conditions for the migrant labourers who were building the Guggenheim and a number of other cultural institutions on Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island. It was only part of a wider concern about labour conditions in the Gulf that has been spotlighted by Amnesty International, among others, and has spawned a number of affiliate protest organisations, such as Occupy Museums.

Perhaps he was simply extending the dialogue that is begun when one begins to talk about being more egalitarian (although not exactly democratic) about whose stories museums choose to tell. Because once you set out on that path there’s no sitting on the fence, you can’t allow some stories in and keep others out. More precisely, there is no ring-fencing or setting limits: you can’t say ‘we’ll talk about these victims, but not those victims’. To do that is to lose your moral authority, the one that you built up by telling those ‘other’ art histories in the first place, and become instead the perpetrator of another injustice. Moral authority is all curators, critics and other arty types seem to want to accrue these days. Although someone more perverse than I might argue that, these days, leaving a few injustices uncorrected (whether by mistake or design is a debate for another time) is precisely what keeps museums going generation after generation.

Or perhaps, more generally, this episode (the question about the Gulf death zone) is a reminder that there are limits to art’s agency. In this case, it’s limited to fixing the flaws of history and the past biases of those who got to write it and control its dissemination, but is unable, in many ways, to address the problems of the present. However much you invest in building an innovative, future-facing structure in which to house the thing. That’s just the emperor’s new clothes.

Until pretty recently, Sri Lankans looking for a place to die didn’t actually have to travel that far, thanks to a civil war that officially lasted from 1983 to 2009 (but, some would say, started earlier) and culminated in what many people describe as the state-authorised genocide of Tamil peoples in the north of the country. You could see the lasting impact of the conflict during KALA at an exhibition hosted by the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) Sri Lanka titled Total Landscaping (12 September – 29 March; adjacent to, rather than part of, the festival itself). The MMCA occupies a ground-floor retail space in a city-centre shopping mall, a far cry from the Guggenheim’s projected conglomeration of titanium bells and whistles. The exhibition unfolds in three acts (or three exhibitions), and the second was on show when I was there, presenting the work of nine artists with a focus on how a land is charted or mapped and how that affects our perception of it – verbs like ‘to border’ and ‘to chart’ were printed on the wall along with definitions as part of the exhibition labelling.

There were works such as Jasmine Nilani Joseph’s Unveiled Barriers (2019), a series of delicate-but-precise pen-and-ink drawings in the Pop style of a 1960s architecture illustration, which explored the sea as both a source of connection and escape, and a form of barrier and prison (complete with turrets and fences). But the show was dominated (physically and conceptually) by T. Shanaathanan’s Drawers of War Transactions (2019), a series of eight wooden cabinets in the form of pyramidal plan chests. Each labelled drawer of which contained a document issued by the government, its insurgent Tamil counterpart or an NGO: resettlement forms, gold ‘donation’ forms (a form of tax levied by the militant Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, which was fighting for an independent Tamil state in the north of Sri Lanka), cattle vouchers (for cows donated by NGOs), emergency travel documents and so on. Each drawer contained one document and an index card featuring a drawing and a typed description of the document in question. Some of the drawers were beginning to stick, either resisting opening or refusing to close. It felt as if the object were somehow defying the imperative to function as an artwork. Or the imperative that every archive that enters a gallery should reveal itself, that the world should contain no secrets. Or maybe it just wasn’t built to last. To have too much attention.

The work was commissioned for the Sharjah Biennale 14 in 2019. In the UAE. And presumably, at that time, there would have been some nervousness about exhibiting a work that contained and preserved ‘official’ documents issued by an authority that was not the official government of Sri Lanka in Sri Lanka. (Just as there might be nervousness about exhibiting documents, say, issued by Hamas today.) But when I saw the work, I was thinking more about whether or not the drawers sticking was somehow connected to the difficulty of showing the objects they contained. A ‘sticky drawer syndrome’ that plagues institutions on a more general level. Which might well be another way of describing the interrogator’s complaint back at KALA. Perhaps some drawers become sticky and some are designed to stick. While you didn’t want to force Shanaathanan’s drawers when they refused to open for fear of breaking them (that is, after all, how we are conditioned to behave in art institutions), you are nevertheless left feeling that the ones that didn’t cooperate were hiding something from you. Even if you didn’t exactly put all your effort into looking for it.

Just a few months earlier I had been at the 421 Arts Campus in Abu Dhabi to see a travelling iteration of the eighth edition of the Colomboscope biennial (Unveiled Barriers had been commissioned for the sixth edition, for what it’s worth), titled Way of the Forest, which, broadly speaking, recast forests as centres for healing. (Yes, the Gulf is definitely where a lot of South Asian art goes to be exhibited these days.) In the Sri Lankan capital, the previous January, the show had featured the work of more than 50 artists; there were works by 19 artists in the version that had travelled west to the Emirate. Some works on show were part of the original exhibition, which was to some degree remixed ‘to engage audiences in the United Arab Emirates’, with the new commissions added around it to a rhythm of keywords such as ‘Ecological’, ‘Extraction’, ‘Stewardship’, ‘Indigenous’, ‘Conservation’. These were printed next to an introductory text on the opening wall, along with definitions. Much as the verbs would be in the Total Landscaping exhibition in Colombo. Although a cynic might say that this, at both institutions, is about channelling the buzzwords of our day before anything else. Perhaps it’s an alternate form of institutional nesting, to use Bachelard’s term.

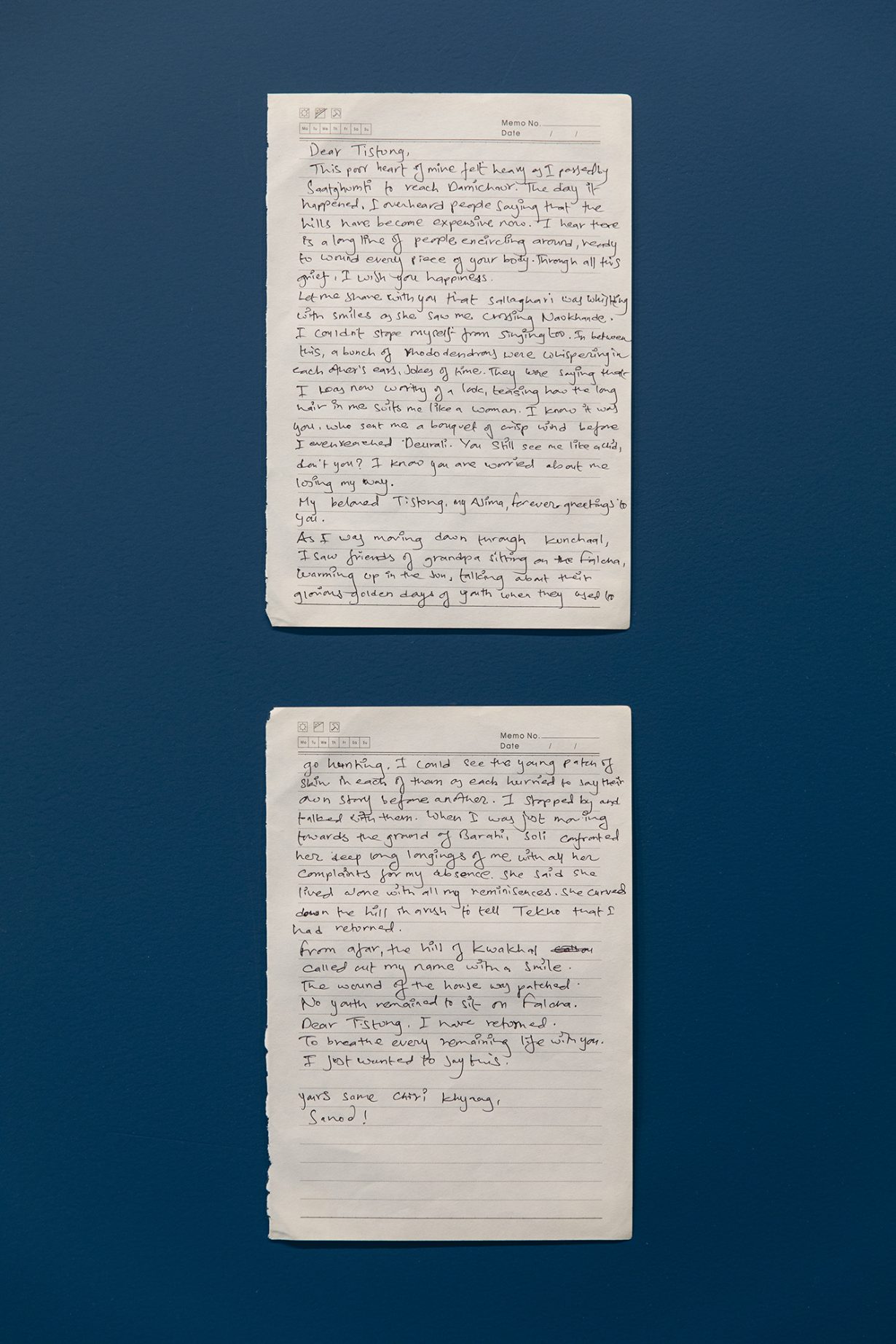

In Abu Dhabi, there are more words and a different kind of nesting in Sanod Maharjan’s Letters to the forest spirits (2019–), a mix of letters written on A4 office-memo paper and letter-size paintings on canvas and board. The artist is from Tistung, near Kathmandu, which used to be a key trade route to Nepal but has now fallen into decline, with much of the local population leaving for the promise of a better life elsewhere. The paintings depict trees and clearings, forest scenes. Their size is a little quirky – designed to be portable before being impressive – which gives them a feeling of immediacy and intimacy, particularly given that they are installed in a salon-style hang. But they are neither especially remarkable in stylistic terms, nor in terms of the particular scenes they represent. But the letters interspersed within them suggest that there is a lot more going on.

‘Beloved Devban,’ reads one (you might interpret Devban (in Hindi/Urdu) as something like ‘God’s forest’), ‘The second of oldest grandmother says that I lived because “Ajima” caught my hand. She even dares to say that anybody living in Testu is immune to unfortunate accidents. Forest spirit Chunn lives here; two of the rivers surround it and keep it here. It has been six months since I nearly lost my life. Mother says that you saved me for the third time… Whenever I got nauseous on the bus to Kathmandu, I used to look at you and comfort myself. Sometimes my mother weeps loudly in your memories. I have heard stories of you, time and again and I feel you have always lived in me. I have always lived with you.’

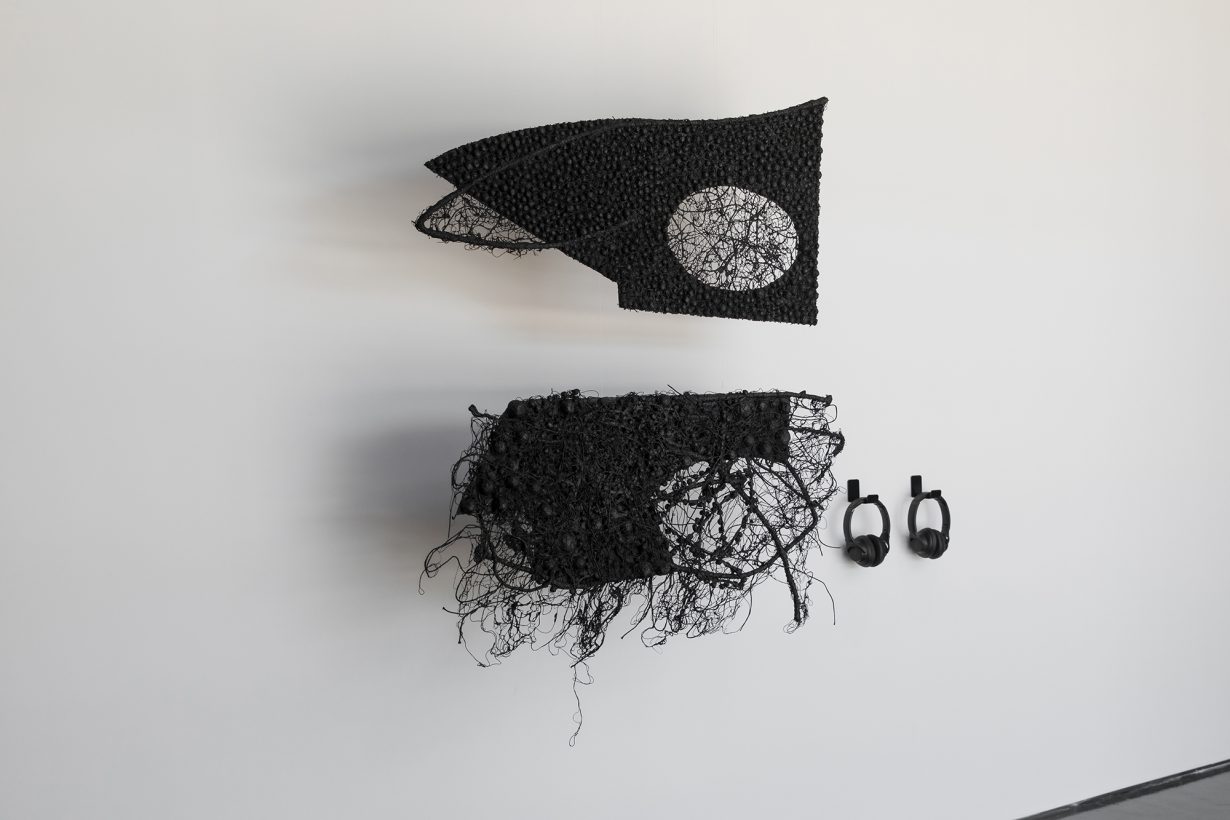

The complete meaning of the letters remains opaque, but in their mix of animal, mineral and vegetable, they contain a connected, animist idea of ‘home’ within them, and convey the notion of the ‘Chunn’ forest spirit as a sort of guardian of both the forest and the people who depend on it. Somehow it’s fitting that whatever Chunn is exists in the space between word and image in this work. Neither one nor the other, like something designed to be lost in translation, unknowable outside its original context. There’s a similar vibe going on in Uzbek artist Saodat Ismailova’s three-channel video Arslanbob (2023), filmed in a walnut forest in Kyrgyzstan. The walnut trees are said to release hallucinogenic gases, and the video has a dreamy, trippy feel as it moves between religion, mythology and more-than-human lifeforms. In short, this Abu Dhabi version of Colomboscope used ‘the forest’ as an excuse to take you someplace else, but also framed ‘home’ as a place to leave and return to. As something that is both physical and more than physical. Something that you can take with you. Not that everything was so hippy-trippy: Pushpakanthan Pakkiyarajah’s installations Hidden Mycelium in a Wounded Land II (2022–23) and Mycelium and the Charred Landscape (2022) offered up a soundscape of Udukku drumbeats (invoking the goddess Pattini, who is associated with fertility among Tamil communities in northern Sri Lanka and South India) and netlike sculptures representing mycorrhizal networks (the everything-is-connected vibe), but ones that appeared to have been charred or caught in an oil slick: a reference one presumes to both the human and nonhuman casualties of the Sri Lankan civil war.

For all the vibe of interconnectedness, however, the discourse about environmental degradation and protection appeared to be referring to something happening someplace far, far away from Abu Dhabi. The UAE doesn’t have any primary forests, so it’s understandable that the show would work differently here, and operate at a certain remove from the postindustrial port environment in which 421 is housed or from the desert landscapes you might find out of town. And to what extent 421’s audience included the 150,000 Sri Lankan nationals currently employed in the UAE, the majority of whom work as labourers or domestic workers, was hard to ascertain. Moreover, it’s hard to think of Abu Dhabi being part of the Global South or Global Majority – from which general grouping most of the artists in this exhibition might be said to come and with which the Gulf in general, from Guggenheims to Sharjah Biennials, is seeking to align – which in turn might suggest that those terms are much more fluid and contingent – cruel people would say meaningless – than we would like them to be. However much both may be du jour in the wild world of art right now. Whether you see that as a way of talking about what can’t so easily be articulated with reference to home turf, or whether that’s about pretending all your problems are someone else’s, is up to you, the visitor, to decide. That, in a way, was 421’s sticky drawer. Amidst Pakkiyarajah’s tangled nets, it isn’t entirely clear whether it’s the aftermath of war or the climate crisis that the artist is talking about. Seen in the Gulf, the oil slick vibes came more to the fore. Perhaps it’s not important. The end result – death – is just the same.

From the Spring 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.