“The most intimate aspects of our life continue to be shaped by imperialism, which means that some of the most intimate patterns of experience are shared”

Known as one of today’s key proponents of and thinkers around the reversal of imperial violence, Ariella Aïsha Azoulay is professor of modern culture and media at Brown University, in Providence, and has written extensively on photography and political theory. She is also a filmmaker, curator and author, and published her first children’s book, Golden Threads, in February. Azoulay, an Arab Jew of Algerian origins, has focused her recent work on the historic ummah, or Muslim community, that stretched from Central Asia to North Africa, where Jews were once protected under Islamic laws and shared many customs and much heritage with their Muslim neighbours. ‘I am also a Muslim,’ she writes in Jewelers of the Ummah: A Potential History of the Jewish Muslim World, published last year, ‘because my ancestors didn’t know they weren’t.’ The book comprises 16 letters she wrote to her ancestors and chosen kin whose life and work were intertwined in the legacy – or erasure – of precolonial Algeria, the Maghreb and beyond.

I first came to know Azoulay’s work as a student of the history of photography. Reading her famous thesis The Civil Contract of Photography (2008) allowed me to see a photograph not as a disconnected image for consumption but as a record of actions and relationships – between the photographer, the photographed and us, the future spectators – that made an image possible. It’s a series of conditions that shaped the world, in which we’re always implicated. Today, with ongoing wars and genocides turning human bodies into abstract numbers, pixels and dust – and as our increasingly technocratic world forms a seemingly detached reality of its own – Azoulay’s work continues to shed light on how we understand our digital reality, the politics of looking as well as ways to unlearn the colonial modes of thinking many of us inherit. Ahead of the premiere of her film One Thousand and One Jewels – Unlearning Imperial Plunder III at the Decolonial Film Festival in Paris in May, we sat down to speak about pasts, futures and how we might be able to reclaim a lost world.

Don’t Fence Me In

ArtReview You work across genres: academic and children’s books, film and photography. How did you come to work in this way?

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay What you list are not simply categories of genre, media or means of expression, so my answer will first have to engage with how such categories have been shaped such that we assume their separateness and that each has its own sui generis history and set of rules. We are talking about imperial technologies in the broader sense – photography, film – but the production of children as a group apart is also an imperial technology; children were invented and used as part of the European imperial enterprise of destruction of life worlds of different groups around the globe.

In all my work I find myself suspending imposed boundaries such as these; I do so not for the purpose of creating an interdisciplinary practice – which reinforces those disciplinary boundaries – but rather in order to shift the centre of gravity away from media-specific narratives and towards shared histories of colonised groups. Dispensing with these imposed categories enables me to attend to their/our needs and to reclaim their/our traditions and memories despite the ways these media were used to dispossess us from our worlds.

In retrospect, I recognise this motivation to think against imperial categories of media and genre in The Civil Contract of Photography, a book that I wrote against common histories and theories of photography – which focus either on the devices or on the photographers. The imperial fusion between those histories, the art market and the museum – what later I called ‘the primitive accumulation of visual wealth and capital’ – turned the photographed person into a present absentee. The book’s point of departure is very simple: the photographed person was always there, and yet they were not accounted for – neither when photography was institutionalised nor when their labour and presence were extracted in the production of photographs of this visual wealth.

So, to answer your question, instead of replying in terms of discipline or genre, I’ll invoke Ecclesiastes’s notion of time: ‘A season is set for everything, a time for every experience under heaven: a time for being born and a time for dying’. For me, there is a time to make a film to speak with and alongside other voices, and a time to write a book that addresses children – it all depends on where I am in the world and whom I’d feel motivated to address, with whom I’d like to be in conversation, and how. I made my first film, A Sign from Heaven, which engages with three models of taking life under a settler colonial regime, since simply writing about this topic was totally insufficient. I wrote my first children’s book when I became a grandmother, and telling young descendants of the Maghreb where they belong was urgently pressing, since the West continues to manipulate the history of diverse Jews to justify the genocide in Palestine.

How to Destroy Knowledge

AR This idea that categorisation of disciplines – or in your words, media-specific narratives – is an imperial technology is very interesting. It seems like you’re implying that the categorisation of disciplines and that of people are the same process of dispossessing and separating knowledge from the world where they’re produced.

AAA It’s not the same process, but a part of the same imperial enterprise of destroying existing types of knowledge.

I could reply to your initial question by accepting the question and speaking about myself as unlike common academics – ‘I am also engaging with cinema or with photography and with children’s books’ etc – but this would say something about how I navigate within the division of knowledge, not so much about the division of knowledge itself.

What I wanted to emphasise is that imperial technologies – those that we associate with ‘progress’ or with ‘modernity’, or let’s say device-based technologies like photography or cinema – those technologies were imposed as a form of generating knowledge that has its own separate history. And in that way we can write the history of photography and the history of cinema separately, without seeing how they are part of the same imperial enterprise that is based on extraction.

What I meant is that the invention of childhood is also a technology, and it is a technology that engineers the life of humans – similarly to the way other technologies engineer the life of nonhumans. So I wanted to speak about how all those technologies together normalised the idea that different types of knowledge exist separately and we are just transgressing them. It is necessary to recall that these divisions of age groups or types of knowledge didn’t exist, and are not unavoidable. We have much to learn from – and aspire to – the way visuality, for example, was enmeshed with justice in some precolonial cultures.

AR A large part of your recent work revolves around the Jewish Muslim world, which also suffered from a kind of division that turns Jews and Muslims against each other. And you often use the terms ‘Arab Jews’, ‘Muslim Jews’ and ‘Jewish Muslims’. Are these different? To many this might read almost like an oxymoron, as today Muslim and Jewish identities are understood as religious and racial, even. What’s at stake in these terminologies?

AAA Before replying to your question, let me emphasise that it is not that divisions are necessarily violent, and that the opposite is necessarily better. It is the colonial, imperial or capitalist way of imposing divisions with force – or amalgamating divisions, as with the imperial violence against diverse Jews, for example, who were forced to be identified as a singular people.

My new book, The Jewelers of the Ummah, deals with the macro and micro forms of violence that destroyed the presence of diverse Jewish groups in North Africa and the Middle East to such a degree that the idea of their shared existence with Muslims – expressed in the categories ‘Muslim Jews’ or ‘Jewish Muslims’ – can seem to some an oxymoron.

Jews were protected communities under the ummah – the Islamic nation – since its inception. The destruction of their presence within the ummah is the outcome of several colonial projects but also part of the Euro-American campaign of violence that, in the wake of the Second World War, invented the Judeo-Christian tradition in an effort to absolve Europe of its crimes against Jews and finally ‘solve’ the ‘Jewish problem’ through the sacrifice of Palestine and the conversion of Arabs, Muslims and Palestinians into the enemies of the Jews. The challenge and goal of the book, though, is not to come out with the ultimate category to designate an identity but to make the Jewish Muslim world – a world in which the Jews were Muslims, Arabs, Palestinians, Amazigh, Andalusian – imaginable again.

Love and Craft

AR I remember reading Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me, where he writes, ‘Race is the child of racism, not the father’. It feels like a similar dynamic here, where differences are only racialised and reified under an already racist ideology.

In relation to this European project of racialising the world, your recent children’s book, Golden Threads, is built on colonial photographs taken of Algerian women and girls, which to me was very exciting to learn, since in my own research I have attempted to understand a disappeared Manchu community – my own ancestors – via ethnographic photographs taken by European travellers. It proved to be a very difficult world to rebuild via these Orientalising camera lenses.

AAA Criticising the practices of colonial photographers and the industry built around the Orientalist depiction and circulation of colonial images of our ancestors is important, but we cannot stop there, since this visual wealth is ‘ours’ – that is, all those whose colonised ancestors were robbed of their presence in order to enable the accumulation of visual wealth to exist in Western museums and archives, and all those whose ancestors’ modes of life were transformed into specimens of bygone worlds – to be studied through the mediation of the museum. Photographs of colonial officers taken in the Maghreb are still treated as authoritative references for the study of jewellery, often with no questions asked about how these photographs contribute to the destruction of the world they ‘document’.

I wrote Golden Threads against the premises of this kind of colonial photography, which turns girls into hangers for the presentation of those marvellous jewels that their parents made, before colonialism destroyed the infrastructure of their making. The book restages these girls’ world and depicts them as the daughters of the craftspeople who worked in the mellah (the Jewish quarter) in Fes. They grow up, learn, eat, play and sing in those workshops where their parents work, and they learn how to take care of the shared world through love and craft.

It is also an homage to the old tradition of Jewish guilds and to the Jewish corpuses of laws that protected the rights of artisans, among them the right to go on strike, which is described in the book. The young readers of the book will learn from this group of five girls an important lesson that is not taught in schools: the necessity of going on strike when faced with injustice. My hope is that after reading the book, when its readers encounter these girls or others like them in colonial photographs, they will remember that they are looking at girls who participated in one of those strikes against brutal colonial industrialisation and that the meaning of industrialisation was the destruction of their modes of life.

Becoming Our Ancestors…

AR This dynamic of reading these ‘documents’ and ‘accumulations of visual wealth’ not as some positivist evidence, but as a kind of destruction, a negative process, is really important, and really not acknowledged enough.

Even though Golden Threads is a children’s story, I imagine being able to write a realistic story requires a massive amount of research, especially given the erasure and manufactured amnesia surrounding Algerian Jewish identity. Is this why you engaged with these archival objects in a more creative way?

AAA The majority of my research was done for the writing of the Jewelers of the Ummah, which consists of open letters addressed to my kin and elected kin through which we inhabit the Muslim Jewish world. The idea for the children’s book came while I was writing the letter to my beloved children as part of that project, and I understood that I must resist the unidirectional way we are socialised to think about ancestry and transmission. The coincidence between the death of my parents and the birth of my first grandchild forced me to understand that I too am now an ancestor, and I have the right to choose whether to passively reproduce this colonial disruption of transmission or reverse its curse.

Thus, instead of maintaining that ‘I didn’t inherit much from the Maghreb’ and indirectly accepting that colonialism has the power to end a world life that had endured for thousands of years, I sought ways to renew disrupted paths of transmission that unfolded in multiple directions beyond that of the heteronormative nuclear family, which was engineered by colonialism to sabotage multigenerational transmission. Reclaiming what was not transmitted to me became, at the same time, inseparable from what I can transmit myself. The letters that open and close The Jewelers of the Ummah – the first to my father and the last to the Palestinian author Ghassan Kanafani – are written from the point of view of daughters who refuse to accept the right nation-states bestowed on fathers to move their daughters away from the world of their ancestors.

… Who Were Not Docile

AR You’re very emphatic on the importance of reversing imperial violence, rather than seeing it as unrepairable. Is it really possible to undo imperialism?

AAA For 500 years people have struggled to oppose, repair and reverse colonial and imperial wounds and damages. We cannot allow ourselves to disregard this resilience, which today is emblematised in Palestine, or to reproduce the imperial epistemological violence that has always pressured its victims to move on and forget about the crimes waged against them. Potential History and The Jewelers of the Ummah offer language to account for these continuous efforts to mend and redress imperial wounds, as well as to participate in anticolonial struggle. Hence, my approach is not concerned with the question of whether it is possible to undo imperialism or not; rather it involves using my different hats including, or maybe first and foremost, that of the political theorist and the native speaker of the languages of images and objects, to provide an anticolonial theoretical framework to amplify those efforts and to help orchestrate them across different places and times.

While I was a bit worried that The Jewelers of the Ummah would mainly interest descendants of this world, I’m deeply moved and excited each day I hear from another person originating from a different world who feels the book is also about them, as you also described when recognising yourself in the questions the book opens. This should not surprise us, since despite the very personal research involved in this book, the most intimate aspects of our life were – and continue to be – shaped by imperialism, which means that some of what seems to us to be the most intimate patterns of experience are shared. On this background, the book looks for those truly rare personal moments that occur when people manage to escape the imperial curse and say ‘no’, not necessarily in heroic acts of refusal but minor ones that track across generations. This is extremely important, especially given how we’ve been taught that our ancestors were docile.

AR The idea of potential history is empowering, as it allows us to be inspired and influenced by another moment in time and think outside the present – even though they are always entangled in some way. But it seems like this could also be a tool appropriated by other political ends for perpetuating the Empire. Donald Trump’s election slogan ‘Make America great again’ is, supposedly, another example of evoking the power of a shared past. And potentially the Zionist project could also make a similar argument about its own exiles. Do you think there is a slipperiness or potential for misuse in the theoretical tools you have developed?

AAA These two examples are not ‘evoking shared past’ but on the contrary evoking colonisation, ethnic cleansing and apartheid in the name of one dominant group that considers itself superior to others. In the case of Trump, these are evoked in the name of a prior moment of white supremacy. In the case of the Zionists, these are evoked in the name of an invented history of Jewish sovereignty over a land that was also inhabited by other people. Potential history sets as its foundation the recognition of crimes against diverse groups and the need to attend to these crimes by restoring the condition of their livelihood outside of the imperial formations that are predicated on their exploitation. So, the answer is no – there is no slipperiness.

AR In The Civil Contract you famously argue that our right to see comes with the responsibility to respond. As photographs don’t have inherent truth, and they’re often weaponised to serve political needs, how do we know what to respond to when we are so inundated with images of suffering? And when the idea of indexical truth has become more and more unstable?

AAA In The Civil Contract I try to challenge the liberal fetishisation of the right to see, and understand it as part of the regime that photography created, and speculate the relationship between the different actors – photographers, photographed persons and spectators – as citizenry, where rights, duties and violence are distributed, regulated, challenged and refused. In so doing, I show that photography puts us into a relation with others with whom we are governed that is not necessarily identical to that imposed by the state. Thus, despite not sharing the same status and rights in the citizenry of photography, people can rehearse other formations of power, irreducible to the top–down model of imperial formations. In this sense, the responsibility to respond is not only grounded in the fact that a photograph is shown to us but because photographs (the products) and photography (the practice, event and condition) are sites in which those differences between the governed manifest themselves in a way that we can understand how much who we are and the positions we inhabit are not disconnected from what is seen in the images.

Idioms such as ‘being inundated with images’, or the older versions of ‘compassion fatigue’, or ‘images of suffering’, are all used to make people think that what is at stake is the circulation of images and not what these images are. The genocide in Gaza made it clear. Palestinians risk their lives to broadcast images of the genocide they are enduring, and they do so against a global project of silencing this truth. It was never about the quantity of the images or on how many images of violence one has to see in order to respond or take action, but about how to respond to images in a way that recognises the truth they bear: that the Palestinians are alone to broadcast a genocide from a zone forbidden to anyone who is not part of the genocidal army.

AR To me this ‘fetishisation of the right to see’ almost echoes what you called the ‘accumulation of visual wealth’, in a capitalistic way, and takes seeing or imaging as a given, and as unlimited, while the labour or extractions that happen in the process are downplayed.

AAA There is something very tempting in photography to think about the individual photograph that is made by this or that photographer or is now in this or that collection; or about an individual encounter between the photographer and the photographed person. It is very tempting to stay at the level of the single image or event. But when we understand the invention of photography as based on, or informed by, previous imperial technologies like land grabbing and extraction of resources, we see that the West operated photography – not just cameras – to achieve much more than is in discrete photographs.

Western actors – entrepreneurs, inventors, operators, scholars, anthropologists, soldiers and others – accumulated a visual wealth that landed in their museums, archives, libraries and private collections. This ‘primitive accumulation of visual wealth’ is in the hands of the West in the same way that they extracted other forms of resources, which enriched them and empowered them to destroy more. What I’m trying to reckon with is this dimension of photography, and at the same time, to decentralise the authority of those who own this wealth – to resist how they determine what was left to us to aspire to.

So rather than limiting my engagement with this colonial legacy to criticising the photographers and their manipulations of the photographed scenes – by staging these women depicted in colonial postcards with their jewelleries – I engage in a conversation with my ancestors, whose images were literally taken and claimed. It’s a conversation that shows that not only these jewelleries are mine, but also this know-how is still alive despite the museum impulse to kill it.

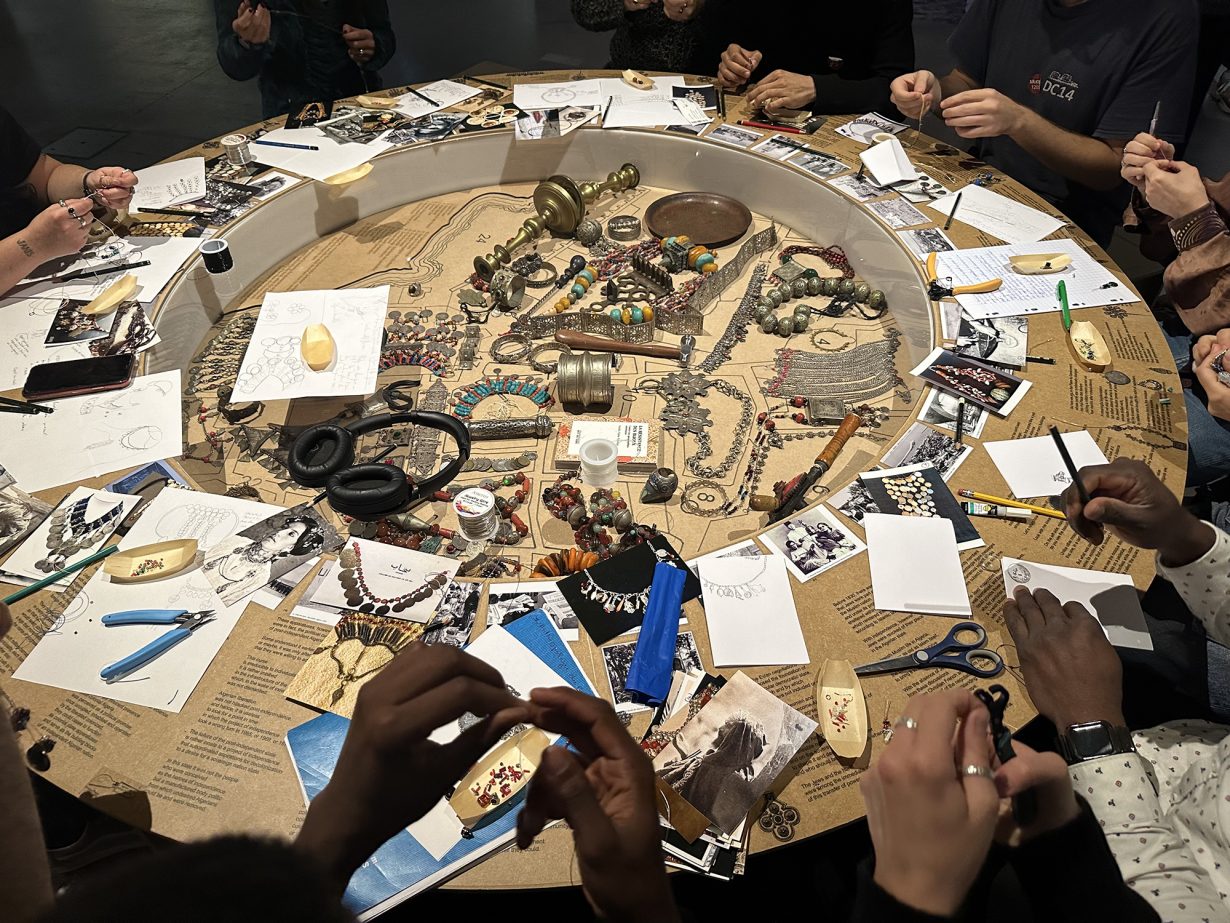

The question though is how I engage with this visual wealth that is accumulated in the West in a different way. In the ‘Fabrication & Narration’ workshops that I’m doing, we are reclaiming together not only those pieces of jewellery but this knowledge that the museum played an active role in destroying its infrastructure and disrupting its transmission.

Calling All Shahrazads

AR Your film One Thousand and One Jewels – Unlearning Imperial Plunder III will be coming out soon. Relating to The Jewelers of the Ummah, this one seems to be about ‘the jewels of the Ummah’. There seems to be a relation between objects and people that you’re always thinking about. Could you speak about how you carried out the project?

AAA Part of the film was shot around the ‘Fabrication & Narration’ table, where descendants of the Jewish Muslim world come together to share stories about pieces of jewellery from the Maghreb while fabricating them, and vice versa, fabricating while listening. In the middle of the table is a map of the destroyed Jewish Muslim quarter of craftmaking in Algiers, which I retraced with found and remade pieces of jewellery from the Maghreb. This table and the film are part of my attempt to decentralise the museum as the source of authority for teaching us, descendants of this destroyed world and guardians of these jewels, what their meanings and uses are, as if they belong to the past and as if imperialism truly succeeded in disrupting our ancestral transmission. The premise behind the film is that as long as all these Shahrazads tell the story of the Jewish Muslim world, the verdict of its elimination is suspended.

AR Do you feel optimistic about where the world is headed?

AAA While it is hard to be optimistic with a genocide that has lasted a year and a half, I believe that we ought to continue the anticolonial struggle. We owe it to the people who already paid an immense price and continue to pay every day. We cannot lose faith in our multigenerational capacity to overthrow this horrible racial, imperial, capitalistic regime.

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s film One Thousand and One Jewels – Unlearning Imperial Plunder iii will premiere on 21 May at the Decolonial Film Festival, Paris

From the April 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.