“We make these things to communicate with others when we can’t with our mouths or our minds”

The artist Dean Sameshima has spent more than three decades cataloguing queer venues and collecting queer ephemera, almost to the point of compulsion. Where he has felt excluded from spaces and archives as a gay East Asian man, he has used his art practice and formal interventions to insert himself into the narrative, albeit as an outsider, as if at once to say ‘I was here’ and ‘I was not here’. Absence, for Sameshima, also contains within it the preemptive fear of what might be lost. Whether cataloguing or collecting, the urge behind his work is conservational.

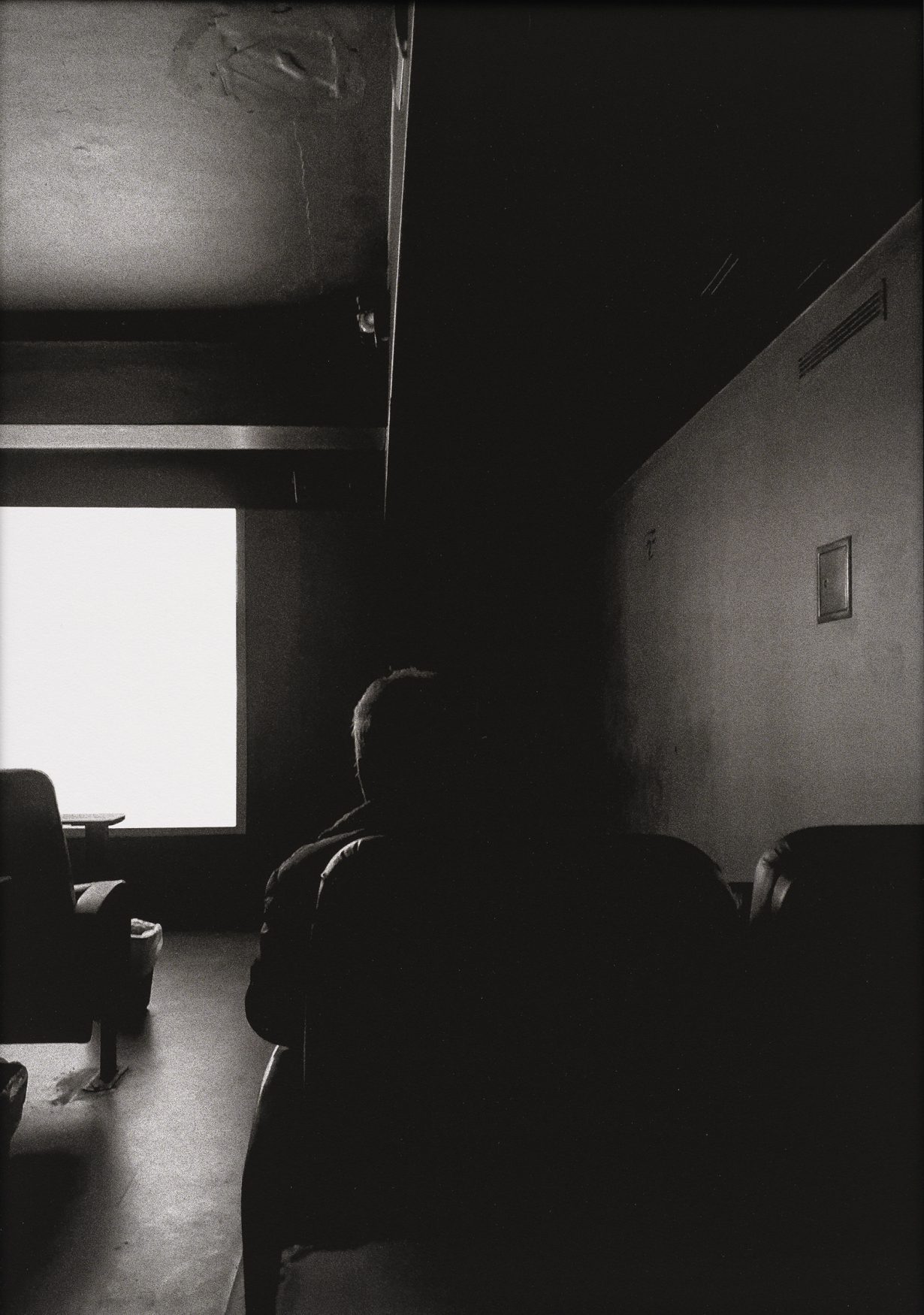

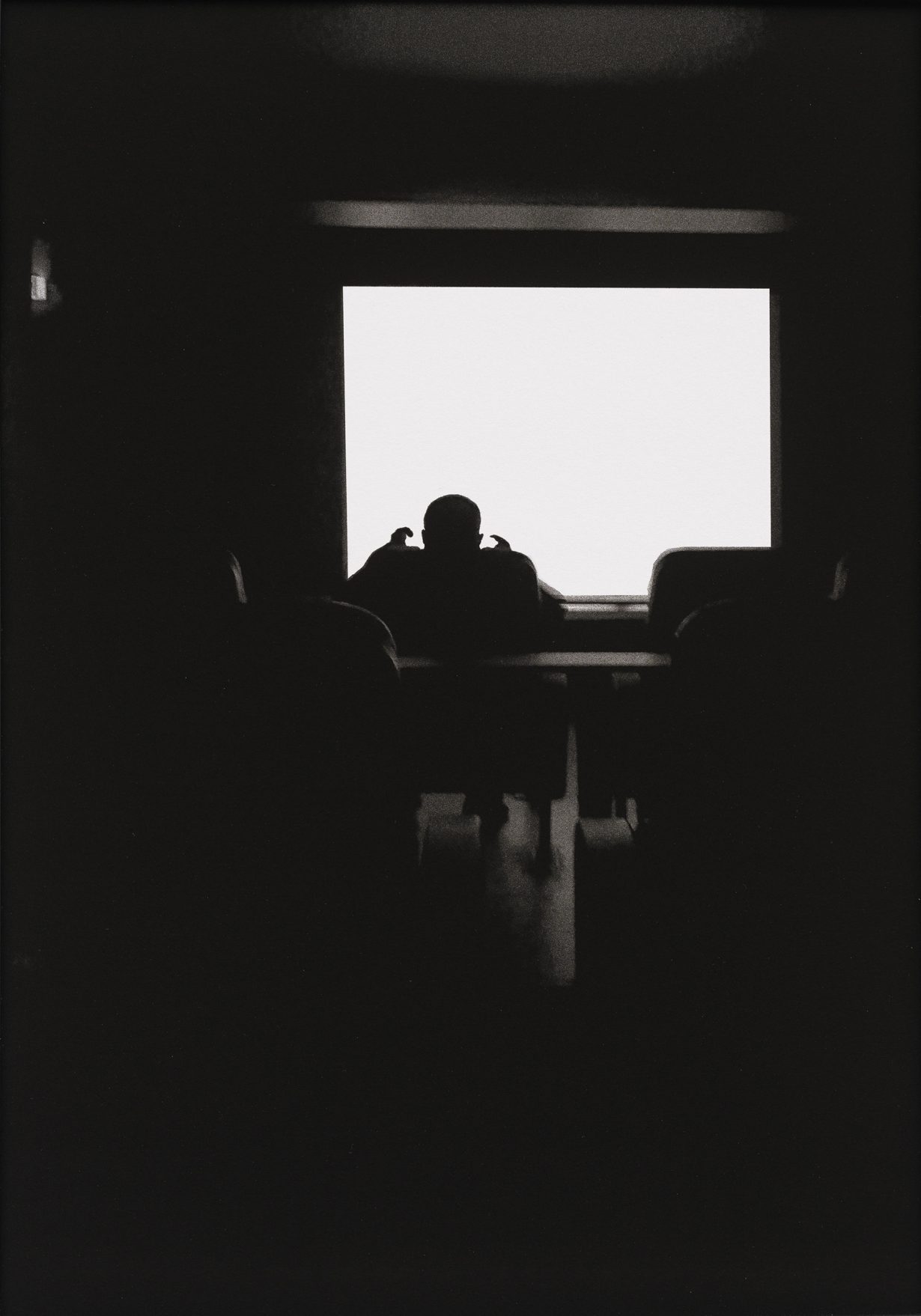

He began his practice documenting aspects of subculture like the LA punk scene he grew up in. Later works document the porn theatres or public bathrooms he’s visited over the years, such as Erdbeermund (2023), in which photos of glory holes become abstracted portals in the context of his frame. The series being alone (2022), meanwhile, which Sameshima exhibited in a solo show at London gallery Soft Opening earlier this year, comprises grainy, erotically charged photographs taken in Berlin’s porn theatres, in the city Sameshima now calls home. While his mediums include painting and sculpture, as well as a penchant for screenprinting that stems from his days frequenting punk shows, it’s of little surprise that Sameshima gravitates towards photography as a quickfire and stealthy means through which to lament the transitory and ephemeral minutiae of the present – while preserving it for the future.

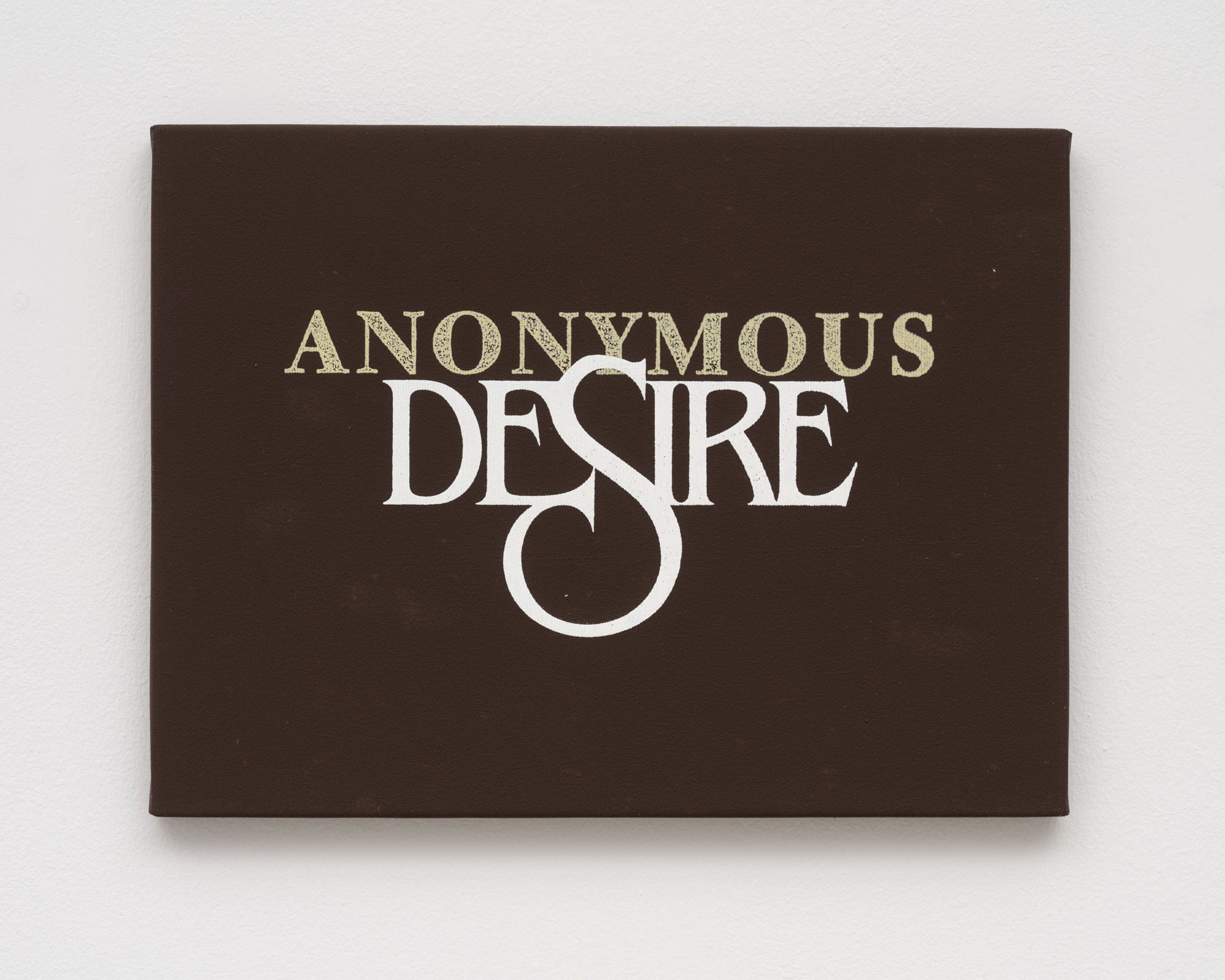

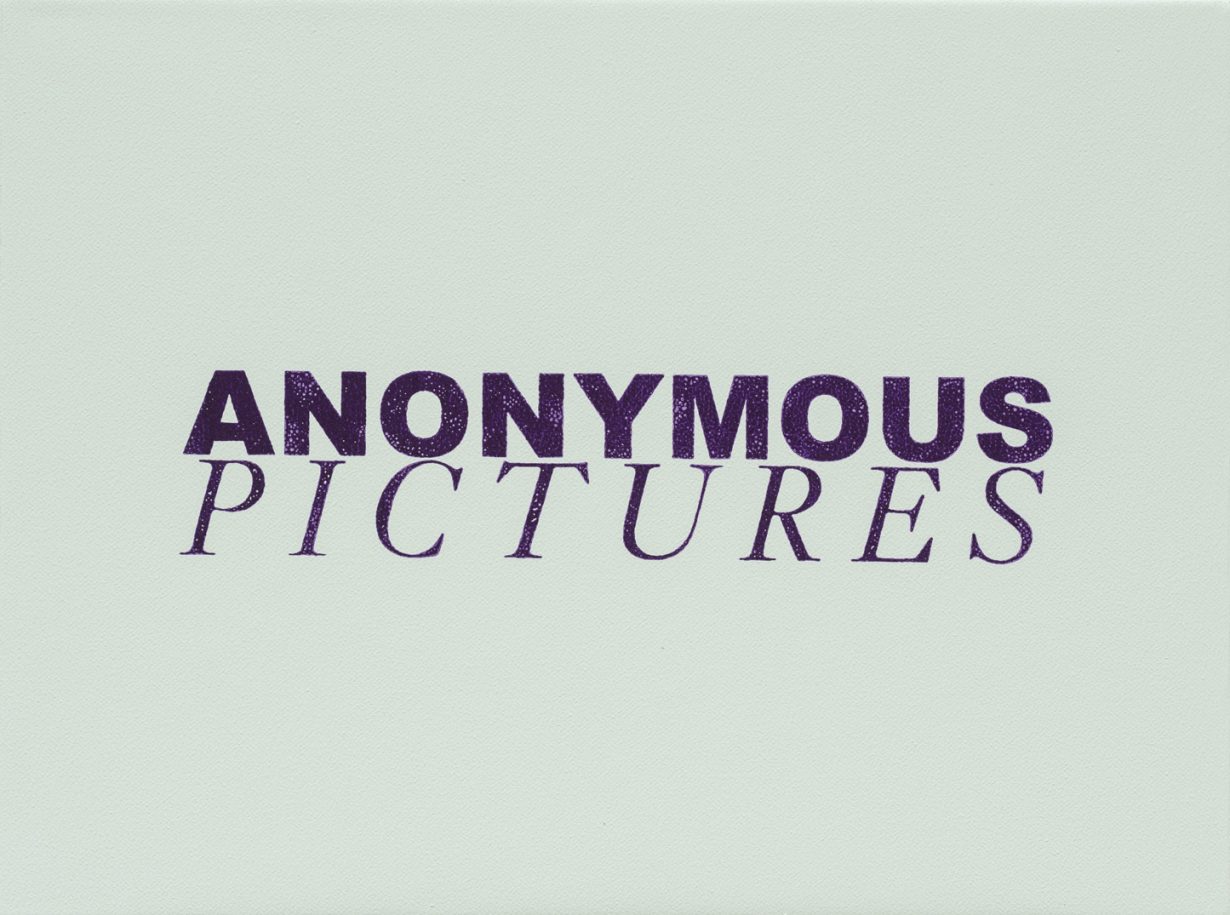

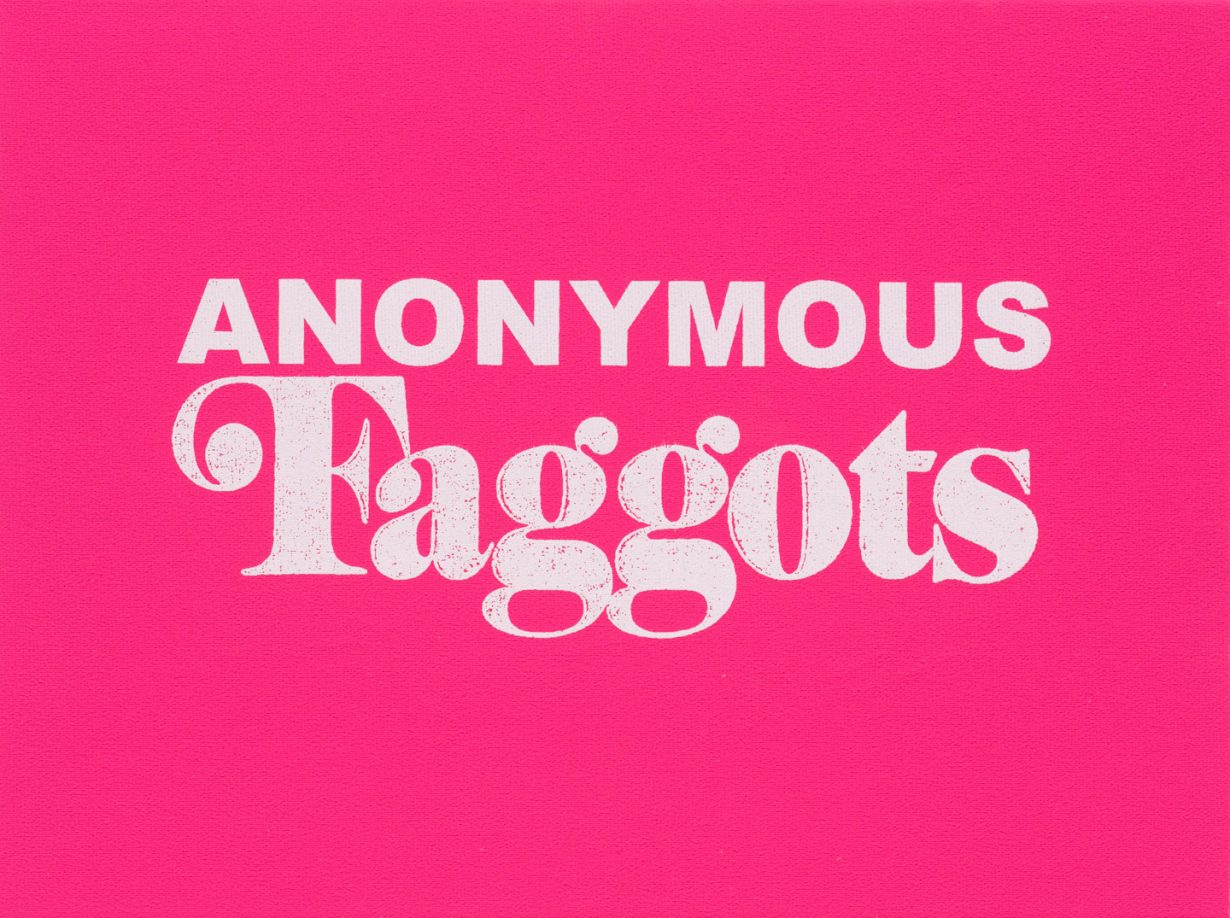

ArtReview Your paintings emblazoned with the words ‘Anonymous Faggots’ and ‘Anonymous Homosexual’ really jumped out at this year’s Venice Biennale. Both because it was the first time I had seen that series and because it contained the word ‘faggot’ on a canvas. Maybe that’s just me. Although I saw a lot of people posting photographs online.

Dean Sameshima I had no idea people were going to connect with the work like that, and it was an amazing surprise. People would tag me on social media. I’d thank them and they’d thank me. That’s all I’ve wanted – to connect with people, because socially it’s been difficult for me to connect. For a lot of artists, right? We make these things to communicate with others when we can’t with our mouths or our minds.

AR The play of the word ‘Anonymous’ repeated across this series creates a paradox: an anonymous figure is placed in various scenarios, conjuring the anonymous act of cruising, but there is an irony in the visibility the work itself has received. What have some of the responses to it been?

DS I think people felt visible. That was meaningful because I’ve always had issues with representation. As an East Asian person in general but as an East Asian male, we are still subjected to the stereotype of the feminine, the comedy relief, the nerd and therefore nonsexual and undesirable. I always felt invisible while at times also feeling like a target for peoples’ racist aggressions. In art, but also film, pornography and fashion, people like me don’t exist. When queer people make works about community, I rarely see people like myself. For the same reason, I try to make work that doesn’t for the most part put a demographic stamp on my ideas.

AR I want to ask you about the repetition of ‘anonymous’ across a bigger series. What is your connection with the word?

DS It came from a dedication in the first pages of [the 1977 book] The Sexual Outlaw by John Rechy. It says: ‘For all the anonymous outlaws… and my mother.’ Reading that really connected with me when I first read it in the 90s because – especially at that time, when AIDS was still new – activists were shaming people in the artworld because they weren’t making the kinds of ‘responsible’ work they thought they should. Being someone who enjoyed public sex was also looked down upon. So I thought Rechy was speaking to me. That’s what I want the paintings to do.

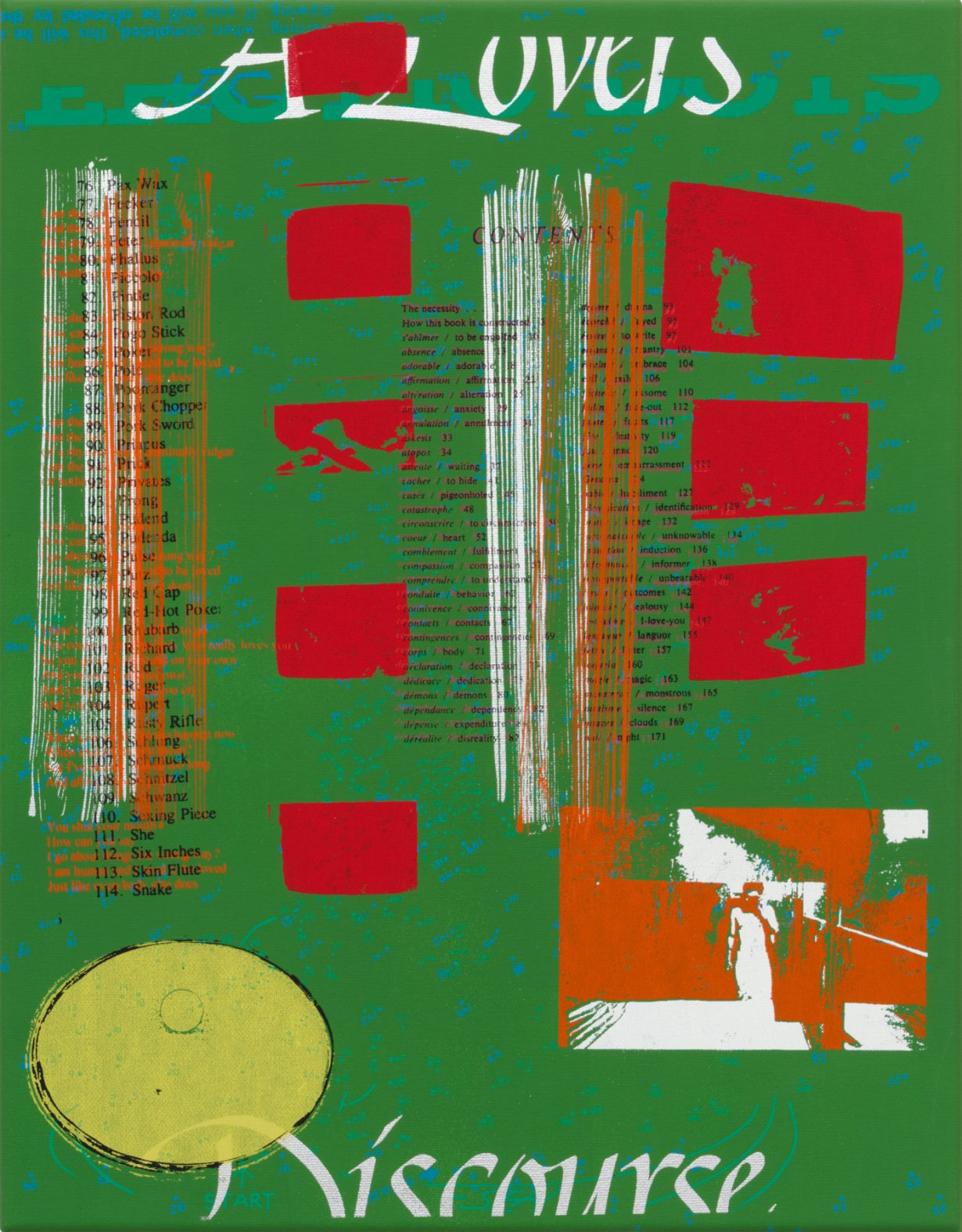

There’s also a connection to sobriety. The font of a few of the anonymous series paintings is taken from the ‘Big Book’, the AA blue book. I’m not on the programme anymore but I’m still sober, and that book was always lying around my apartment, which is also my studio. Since the initial inspiration for these paintings was a book, I pursued that by tweaking typography and colour combinations from texts in my archive library, mostly queer texts. I also wanted to choose from my library due to the laws in the US, particularly Florida and other conservative states, that are banning books. I wonder what would have happened to me in the 80s and 90s if I didn’t have books to connect with gay figures, and how much more at a loss I would have been.

AR Did you notice a shift in your work when you moved from LA to Berlin? Say, the being alone series – they could be taken in LA, or Berlin, or almost anywhere…

DS When I came to Berlin in 2007, I stopped making work. My focus was on getting drunk and high as soon as I woke up every morning until I passed out. Then when I got sober, I couldn’t make work because the wine, cocaine and pills had helped me to feel less self-conscious. So I had to learn how to do it again. In 2020, during the pandemic, something clicked. One of the early series I made was of these boxes of things people left out on the streets in the summertime to give away [Zu Verschenken, 2020–ongoing]. It was my portrait of Berlin. Then I started making portraits of trash cans in the porn theatres. Again, pointing my camera down.

I clean apartments for a living, and was inspired while cleaning clients’ homes and emptying their trash. Actually, part of the reason I had so much time in 2020 was because I lost a lot of those cleaning jobs and was forced to be at home. I started to look at all the photos on my phone, hundreds and hundreds of them. I call them ‘notes’. I noticed these photos of people from porn theatres. That’s when being alone came about. The images of the backs of heads felt more interesting than those from the side. I wanted everything to remain anonymous.

AR What do you shoot on?

DS My phone. But I studied photography as an undergrad, so I’m pretty well versed. Photography was my gateway drug into art. I used to photograph concerts in the 80s a lot. In being alone, I try to make the images look analogue. I play with the grain and contrast, so when you see them in person you can’t tell they’re not.

AR You remove what’s on the porn theatre screen. Why?

DS A lot of us have experienced going to the movies alone, no matter what it is, identifying with what we’re seeing on screen; romance, horror, comedy. We’re immersed. I wanted to keep the sex out of it so you could project your own fantasy or story or feeling.

AR It becomes more about your gaze on the audience, which is sexier, or at least more complicated. We’ve spent a lot of time collectively thinking about the gaze when we watch pornography, but watching people watching it is something else.

DS The spaces I go to are not gay-specific. A lot of the guys don’t identify as gay or bi, or are married or have a heterosexual relationship outside of this space. Women go there too. In these spaces most people are aware, if not hyperaware, of their surroundings. Ninety percent of the people go there to cruise and have sex. Even when people are watching the films they are aware of others. I like that tension.

Also, these spaces are dying out because of new technology. Younger generations are not finding these spaces as useful as they used to. Especially in Berlin. In the US, a lot of them closed long ago. This project is also about this moment before porn theatres disappear. A community that might not exist for much longer. Before it all goes away, I wanted to make sure I had some kind of piece of it.

AR You could watch online at home; you could go on Grindr. Right? But I wanted to pick up on your impulse to catalogue these things almost obsessively – like the street boxes in Zu Verschenken. Have you always been like that?

DS Since I was a little kid. Stamps. Baseball cards. Coins. Then it became comicbooks and Japanese toys. I’ve always been a collector of things. In the 80s I collected punk flyers and records. When I took my camera to shows – smaller goth and punk shows – I documented as much as possible. Or in the sex clubs if they had matchboxes, I’d always be taking something like that to hold onto. It was just in case this disappears or goes away.

AR Your series of photographs In Between Days Without You, of beds in gay bathhouses, feels similar.

DS That series started in 1997. I was fooling around with a guy one night at a bathhouse in California. After he left, I thought, ‘this guy looks so familiar’. I realised he was in my high school. I wanted to remember so I took a photo of the bed that was covered in sweat. I was trying to take portraits of these people without them in the image. Some of the beds were messed up, others were left pristine. It was a portrait of the people, the bathhouse and the time – a time when Felix Gonzalez-Torres had his bed billboards [Untitled, 1991] displayed throughout Los Angeles. But a lot of people were reading a sweetness into that work, the idea of monogamy and coupledom, because it was two pillows in this beautiful bed. This was a time when, as gay men, we were supposed to be making ‘responsible’ work. My photos were a reaction against that, about promiscuity, and multiple partners, and not this heterosexual ideal.

AR The Gonzalez-Torres images were a tribute to loss due to AIDS?

DS Yes, I think he had lost his partner at this point.

AR This idea of ephemerality reminds me of Prem Sahib’s work, specifically what he calls his “sweat panels”, in which aluminium sheets with resin droplets on them, sometimes with the trace of a handprint, evoke the sweat, steam and bodies in a bathhouse. It comes back to what we were talking about earlier: how do we commemorate or grasp onto this experience that was so fleeting?

DS Trying to catch that fleeting moment, that short period of time you had with a stranger. And so you try to make it happen again with someone else.

AR I was reading an exhibition text for a show you did with Peres Projects and McNamara Art Projects in 2017. It read: ‘A nostalgia for a prelapsarian decadence for sexual adventure’. Do you feel that applies?

DS It is happening now – the photos in being alone were taken over the last few years. But my work is often dismissed and placed in this category of gay sex or cruising. I’m trying to let it breathe bigger breaths, and hopefully not make it just about that. I am inspired by spaces of desire, whether it be a magazine, a book page, a porn theatre, the streets. At this point in time I want my work to be about technology, architecture, community.

AR In Jeremy Atherton Lin’s book Gay Bar [2021], he laments how things are becoming sanitised. This is specific to gay spaces, and the fact we often now call them ‘queer spaces’ as part of a push for inclusivity. But is also about claims on public space and policing, while the book banning you mentioned above speaks to an antisex sentiment.

DS What I love about these porn theatres not being gay-specific is their sense of community. I have been denied entrance to gay clubs, bars and sex clubs and bathhouses in the past. I have often had to deal with aggression by white gay men, both verbal and physical. The gay ‘community’ has had a long history of racism dominated by white men and white supremacist ideals of beauty. Society in general has this problem. It may be better now in gay spaces. I don’t know; I haven’t been to a gay bar or club in ten years.

AR Something about your inclination toward screenprinting does feel nostalgic for a time gone by…

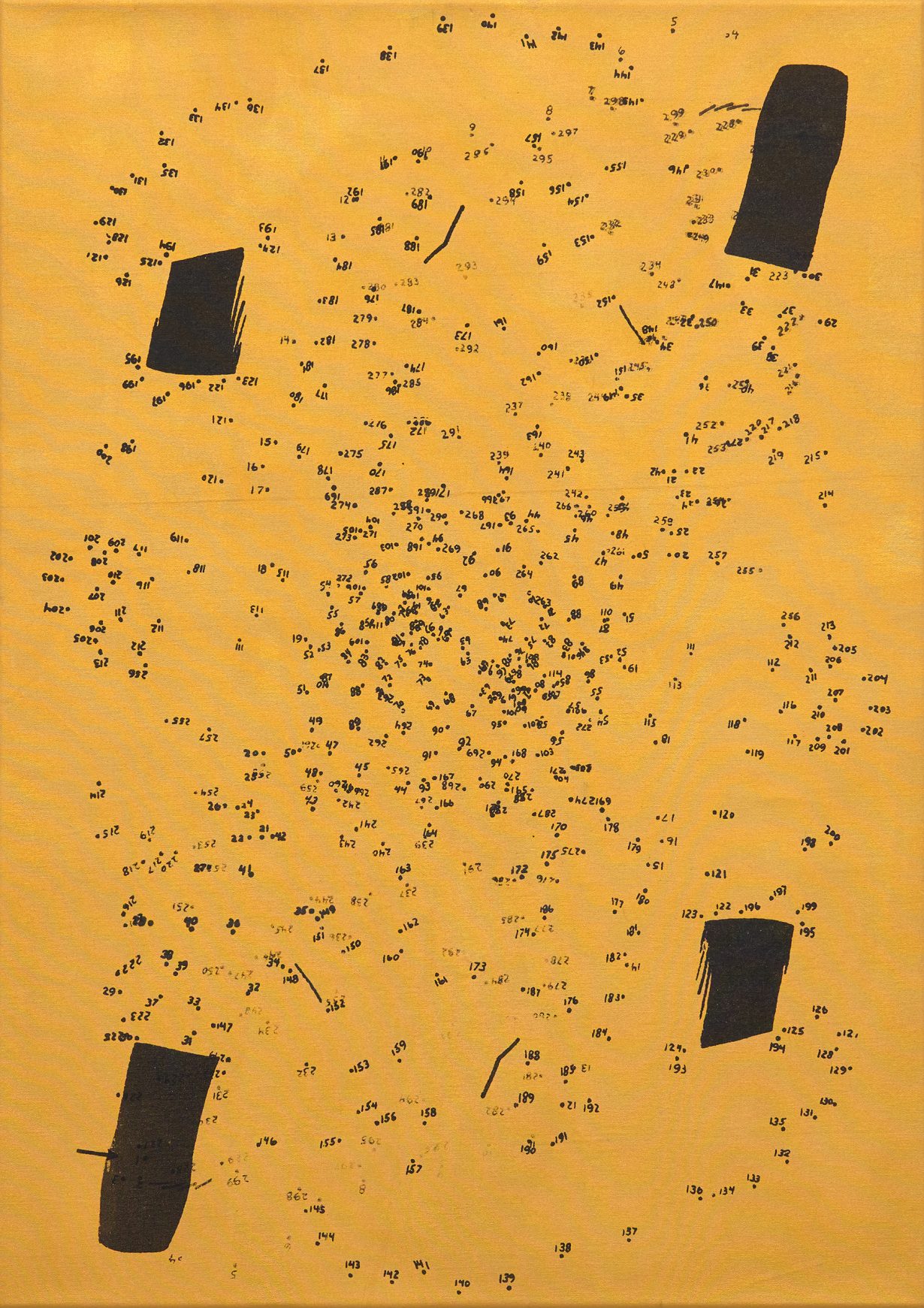

DS Yes. This series of paintings, Figures – some from 2011 and others from this year – are numbered. They stem from my Connected Dots series I did in 2006. Now I’ve started including photographs in my silkscreens. They have photos I’ve taken from the 80s to now, spaces in LA and Berlin; there’s text and my notes. These are inspired by 80s punk flyers – getting a lot of information into a certain amount of space – and Vivienne Westwood shirts, and cut and paste.

It’s an important part of my history, a time when I was discovering music and a community of people in that music, but also coming out to myself. Confusing but also very hot. Punk shows were the hottest thing, a gay boy’s dream. A bunch of shirtless dudes sweating in the mosh pits. Guys beating each other up, hitting each other, this aggression, this homoerotic energy.

AR It’s an experience from your youth that speaks to the being alone series: there’s a spectatorship and a distance.

DS A fear of joining but enjoying what I’m seeing. An observational position.

Amelia Abraham is a writer living in London and the author of Queer Intentions: A (Personal) Journey Through LGBTQ+ Culture (2019)