‘‘I have a really complicated relationship with objectification. I understand it but I don’t like it.’’

Dennis Cooper is a writer of slim, disturbing novels about young, catastrophically beautiful boys who totter through worlds in which violence and sexual abuse are as common as weather. Known for his ‘George Miles’ cycle from the late 90s, Cooper’s most recent novel, I Wished (2021) revisits the real-life inspiration behind his early novels: his childhood friend, a charismatic, deeply troubled boy named George who died young. A difficult book, he has stated, to write; and difficult to read. Cooper’s language is so volatile that its images begin to mutate – a gun becomes a phone in a young boy’s hand, as he presses it against his head and clicks. Though not without the usual Cooperisms (recreational drugs, murder, gory sex, usually in that order) that his readers will know well, I Wished is predominantly elegiac in tone and riddled with holes: rips, craters, exit-wounds, some of which actually speak, though with nothing comforting to say. Holes can sometimes act as portals, a way out, but not here. The time for wishing’s past. Nobody’s stepping through.

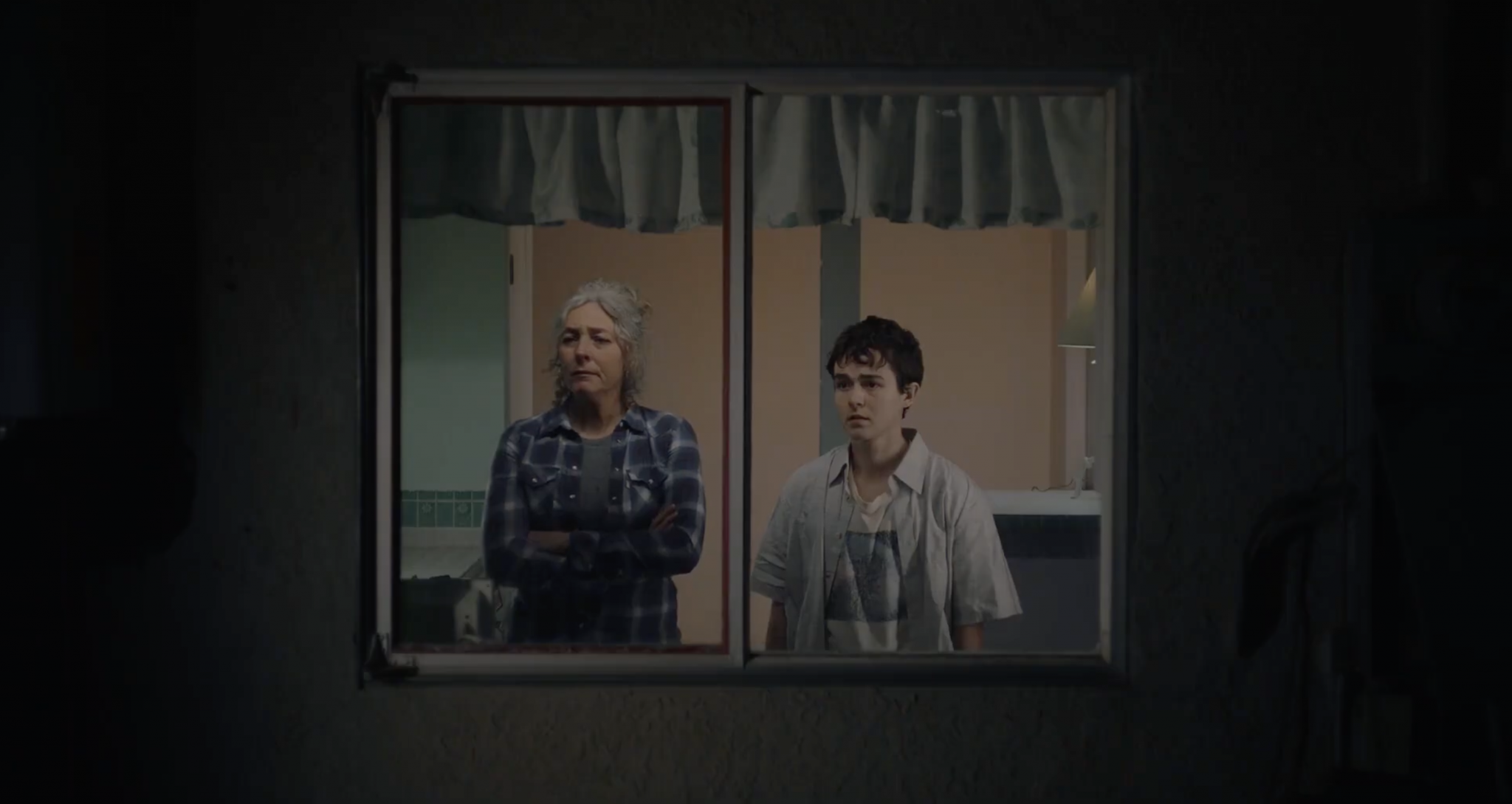

His films are no walk in the park either. They are quiet, stripped back, ready to explode. His latest, Room Temperature (2025) – which began a limited run in cinemas in November – follows a family terrorised by an abusive father hellbent on creating the scariest possible haunted house for Halloween. Cooper’s turn to the medium feels somewhat belated (this is just his third film to date, since 2015’s Like Cattle Towards Glow, made once again in collaboration with the visual artist Zac Farley), because movies appear frequently in his fiction, casting their gloom into sordid basements, playing on a loop. You can probably guess what kind.

Cooper spoke to ArtReview over a video call from Paris.

ArtReview When did you first become interested in haunted houses?

Dennis Cooper I don’t know. I don’t believe in the paranormal. I used to make very simplistic haunted houses when I was a kid. The haunted house really interests me as an art form: to make something that is overly ambitious and fails, that tends to be scary and complicated. I’m interested in the safety and overfamiliarity of it, setting something there and having it be so familiar you don’t even think about it. And then it’s a house that’s not the reader’s house; the character is extremely comfortable but the viewer isn’t. You can do something interesting with that.

AR Why do you think you’re drawn to the imagery of horror?

DC It probably has to do with the play in my work between extreme actions and the realness of them, but also their artificiality, because usually when they happen they’re revealed as being acts of the imagination. So in that sense the language of horror is useful because it’s supposed to be scary. The problem with horror movies is they never feel completely real. But I like taking that and trying to invest it with documentary realness, just enough so that it’s more powerful than those things can handle.

AR You have previously said that structure and control are very important to you as a writer. Is it the same with making films?

DC What excites me about making films is that it happens in increments. You write the script but you don’t know where you’re going to shoot it or who’s going to be in it, and once you start filling those things in it changes. I’m constantly rewriting. And then shooting it is a whole other language. Also, writing for human faces and bodies that are already there is a very interesting assignment.

AR I was surprised at how emotional Room Temperature is. It’s also quite funny. Are you aware of these different tones while filming, or do they surface later on?

DC It’s all planned out in advance. We knew we wanted a particular tone – neutral, introverted, attentive – to run through the film. There are a lot of swerves in it; in the beginning you think it’s going to be something it isn’t, with the flashing lights and all the blood, and then it turns into something else. Shooting films is amazing but the editing is where you do it, that’s where you finesse everything.

AR Desire seems to be the driving force in your work, the overwhelming need to ‘get’ something, but ‘getting it’ often also entails ‘killing it’, and being killed is a fate your characters frequently resign themselves to. When people pursue their desires, the result is often gory.

DC I have a really complicated relationship with objectification. I understand it but I don’t like it. I’ve had lots of friends who were shaped by the fact that people thought they were beautiful. I’m interested in what that does to the person who’s attractive, how it damages them. They have no responsibility for how they look, they can’t take credit for it and yet that’s how people see them. They want people to circumvent that and find out who they really are so that their surface doesn’t matter anymore, which does happen sometimes. But there are always people who just want to conquer the surface. So it’s not so much passivity that’s underrated, but opacity. That’s what interests me, that kind of character. Extra [a character in the film] is like that but he’s much more externalising of his strangeness, so it’s more difficult to objectify him. He’s the character people are most excited by. They’re like: why did you kill him? Because it bothers you, that’s why! And then it’s sad, because he has to wander around as a ghost, probably forever.

AR I was surprised by the ghost.

DC Well, good. You’re supposed to be. We like the idea that the only scary thing about the haunted house is the ghost, and nobody knows it is there.

AR Your characters often confuse art with murder. In Room Temperature, for example, the father kills Extra in his pursuit of the perfect haunted house. Can you talk about that?

DC It’s a distancing device. If they’re artists there’s this idea that you should have some kind of respect for them: they’re just making art, so what’s the problem? I like that confusion. They’re doing these horrible things but they think they’re trying to use the body to try to find this amazing thing that they know exists. It’s like when Extra gets killed, we want to take that emotion away.

AR Your sentences are strange and startling. One of my favourites from I Wished is: ‘Reality’s a line where unrealistic things dissipate into sci-fi or become explosives, and I’m that boundary’s bitch.’ It’s very rhythmic. Do you listen to music when you write?

DC No, but music is super influential on my writing. When writing my first novella Safe one of my rules was I had to be listening to the live album from Joy Division’s Still the entire time I was writing. This was before Joy Division was a T-shirt band, just to give myself a little defense there. I’ll stop and listen to things and then write, but when writing I need it to be quiet, or just the little noises from the street.

AR I Wished is, among other things, about the failure of language; there are whole paragraphs that appear to erase themselves: there are a lot of if-clauses that go nowhere, conditional tenses, images that vanish as soon as they are described. Is silence important to you?

DC Very much so, but it’s difficult to do that. You can’t control how peoples’ minds work. A novel is like a drug. There are writers I love that seem to be able to create an affective silence in the text. It’s just very difficult to enact. But it is a goal.

AR Lynne Tillman quotes you in her introduction to your first novel, Closer as saying that novels are a place to put confusion, which I think is lovely, and I wonder: if that’s true, then what are films?

DC Oh. I don’t know that it’s so different. I feel like I put the same thing into everything. The trick in films is trying to make it porous, make it so that you have to pay attention. I would have a film that’s kind of empty and naked and calculated so that you have to pay attention to it. You lose people who think it’s boring, and there’s nothing you can do about that. So I don’t know if that’s confusion. But confusion’s my thing. ‘Confusion is the truth’ is my motto, so I’m sure that’s going in there.

Read next Victor Man: How to Paint Death